Diplomacy and literature, or fine arts in general, can be viewed as the opposing spheres of human activities. In everyday language, diplomatic expression of one’s views very often requires the observation of the rules of ‘political correctness’, which the specific imagery of fiction and the writers’ freedom of expression cannot always follow. To illustrate the opposition between the artistic language and diplomacy we could mention the international scandals around the work of Salman Rushdie, which threatened not only the artist’s life, and the caricatures of Prophet Mohammad.

However, many well-known authors of the world literature have served their countries and earned their bread as diplomats. The memoirs of diplomats form a wide-spread and much-translated part of literary works. Organisation and management of international relations requires better than average speech and writing skills, which could as well be used in enjoyable recording of one’s own experiences and memories.

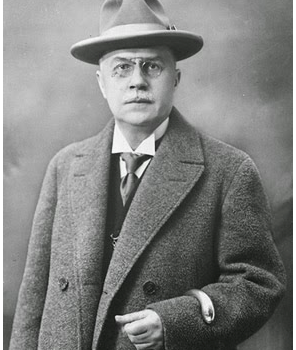

The predecessor of all Estonian writing diplomats was, undoubtedly, the literary classic Eduard Vilde (1865-1933). Vilde can be considered as the first Estonian professional writer; he was a productive author of prose and humorous stories, but also a playwright. Having been travelling in Germany and other areas of Europe already since the last decade of the 19th century, he wrote memorable and educational travelogues. After the revolution in 1905, he spent some time in exile in Switzerland and earned his living by writing for German-language newspapers. Among other newspapers, his articles were published in Die neue Zeit, at that time edited by Karl Kautzky. Later, he lived for a longer period in Denmark, familiarised himself with the spiritual life of Western Europe and wrote a novel Lunastus (Redemption) about the life of Danish workers. In 1911, Vilde travelled to New York. Based on a complaint from a local Estonian pastor who accused him of immorality, anarchism and mental illness, he had to spend several weeks in the immigration prison on Ellis Island. He was so much offended by such treatment that he stayed in America only for half a year.

The Estonian War of Independence and the process of establishing the Estonian Republic were still going on, when Vilde was already appointed the Estonian Ambassador in Germany. He resigned from the post a year later, but stayed on in Berlin until 1923 as a free writer without any inconvenient obligations. He was succeeded as an Ambassador by another art professional, who had patience enough for a much longer diplomatic career – the former dramatist of the Tartu Vanemuine theatre Karl Menning. But neither Vilde nor Menning have written much about their lives as diplomats.

The first President of the newly re-established Republic of Estonia in 1992- 2001, Lennart Meri, came to the politics as a writer. Prior to becoming the President, he was the Foreign Minister in 1990-1992, and for a short period, the Estonian Ambassador in Helsinki, Finland. Meri had read history at the University of Tartu. His travelogues, raising bold hypotheses and reconstructing history and his erudite cultural historical essayist novels are really worth special discussions. In this context, we should only attempt to put into words Meri’s greatest merit as a writer – he revealed the most ancient layers of our memory, revised them and presented them to the public in such a way, which gave boost to research in several different fields of science. “An image is a poetry’s building block, but a threatening mine for science”, Meri aphoristically defined his method in his voluminous historical essay Hõbevalge (Silverwhite). Such bold and enthusiastic relating of fantasy and historical facts, the world perception of folklore and natural sciences, which is characteristic to Meri, is singular in Estonian literature and outstanding in the context of world literature. Works of no other Estonian writer have been so often quoted by specialists of different fields of sciences than the travel books of Meri, written about wind and ancient poetry.

Mart Helme (1949), too, trained as a historian, but later worked at publishing houses and newspapers. In 1979, he published a collection of meditative prose poems Kolm Korvi (Three Baskets). In 1995-1999, he was the Estonian Ambassador in the Russian Federation. He wrote about these years in his memoirs titled Kremli tähtede all (Under the Stars of the Kremlin) (2002), colourfully describing different aspects of Moscow life. Helme did not continue a diplomatic career; having returned home, he soon left the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and now he writes columns for Estonian daily newspapers. Besides the memoirs titled Eestile (To Estonia) of Consul Ernst Jaakson, who represented the Republic of Estonia in the USA throughout the years of Soviet occupation, we should mention that Under the Stars of the Kremlin is the first book of memoirs published by an Estonian Ambassador after the regaining of independence.

In his memoirs, Helme tells us about the time of the establishing of the Embassy of Estonia to replace the representative office of a former Soviet Republic in Moscow. He talks about the border negotiations, which continued to be a difficult topic, and about the non-acknowledgement of the Soviet occupation which has always been a sensitive issue for Moscow. Helme had participated in the process of withdrawal of Soviet army units from Estonia and in the conclusion of the border agreement; both subjects had been the sources of disagreement in relations with Russia. Helme observes the Byzantine foreign policy of Russia, analyses the work style of Russian diplomats, and the influence of Slavophiles and ‘zapadniks’ – those, who appreciated the Western ways and styles. He also describes colourful personalities of foreign diplomats residing in Moscow and Russian politicians. An interesting episode is his description of the reburial of the last Russian Tsar Nicholas II and his family at the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg in 1998. Boris Jeltsin participated in the ceremony, while both the Russian Orthodox Church and the communists kept their distance.

Helme admits in this fluent and enjoyable book that he cannot be only an obedient subordinate. Among other episodes he also describes a small scandal that broke out like a storm in a cup of water when it came out that while being the Ambassador he had, under various pseudonyms, published critical articles on Estonian-Russian relations in newspapers.

Jaak Jõerüüt (1947) has been publishing books of poetry and prose since 1975; he has been given several literary awards. His main work is a two-volume novel Raisakullid (Vultures) (1983-1985), discussing the ethical conflict between consumer-oriented welfare society and humanism. Lately, the attention of critics has been turned to his subtle poetry. Jõerüüt has found a good balanced between diplomacy and literature – in 1993-1997, he was the Estonian Ambassador in Finland, in 1998-2003 in Italy; after that, he worked for a short time in New York with the UNO and lately, he was the Minister of Defence of the Estonian Republic. His memoirs Diplomaat ja mälu (Diplomat and Memory), published in 2004, found warm reception and acclaim with the public and the critics. Like Helme, Jõerüüt, too, discusses the establishing of a new Embassy, this time in Finland, and describes the period when he lived in Rome and represented Estonia in Malta and Cyprus as well.

Jõerüüt the writer has a sensitive and thoughtful nature; his memoirs are written with great empathy and they are ‘diplomatic’ in the best sense of the word. His style is impressionist and elegant, grandiose and at the same time, discreet. The book is rather an essayist diary of thoughts than a customary memoir, but it is enjoyable and it can be seen that the author had enjoyed writing it. Jõerüüt attempts to catch essential things invisible to the naked eye, the mentality of people and peoples, at the same time offering a credible testimony of the events he had participated in. It is thrilling and movable to read the pages about the first steps of the country that had again won its place on the world map, about the study of diplomatic etiquette and about the perhaps exaggerated expectations of other countries, who were, for example, wondering about the Estonian ministers who were expected to come to state visits. It could have been a surprise to meet poets and former dissidents!

It would be unfair, if we did not point out a book written by still another Estonian diplomat. Margus Laidre (1959), a productive war historian who has studied the period of Swedish rule in Estonia and written a number of monographs, was the Estonian Ambassador in Sweden in 1991-1996, then in Germany, and since 2006, in Great Britain. In 2003 he published a voluminous and thrilling book titled Sõnumitooja või salakuulaja? Nüüdisaegse diplomaatia lätted 1454-1725 (A Messenger or a Spy? The Sources of Modern Diplomacy in 1454-1725). This is a thorough research based on extensive amount of source materials, focussing on the emergence of modern diplomacy and the establishing of the system of embassies in Europe. On the other hand, the book contains witty intermissions on a variety of interesting related incidents, for example, about the role played in the relations between Portugal and Pope Leo X by an elephant that had been given to the latter as a present.

Laidre’s book is divided into four cycles Politica, Personalia, Legatio and Diplomatica; it examines the diplomatic job from the time it took a distinctive shape and started playing an important part in relations between different countries, and pays attention even to the microhistory of its trivial aspects. He records outstanding persons and events and describes different customs and traditions. Revealing some shadier areas of diplomacy, he also talks about the development of spying and political murders, and naturally, draws parallels with the present day. His book is full of information for specialists of the field as well as for wider public interested in popular historical literature.