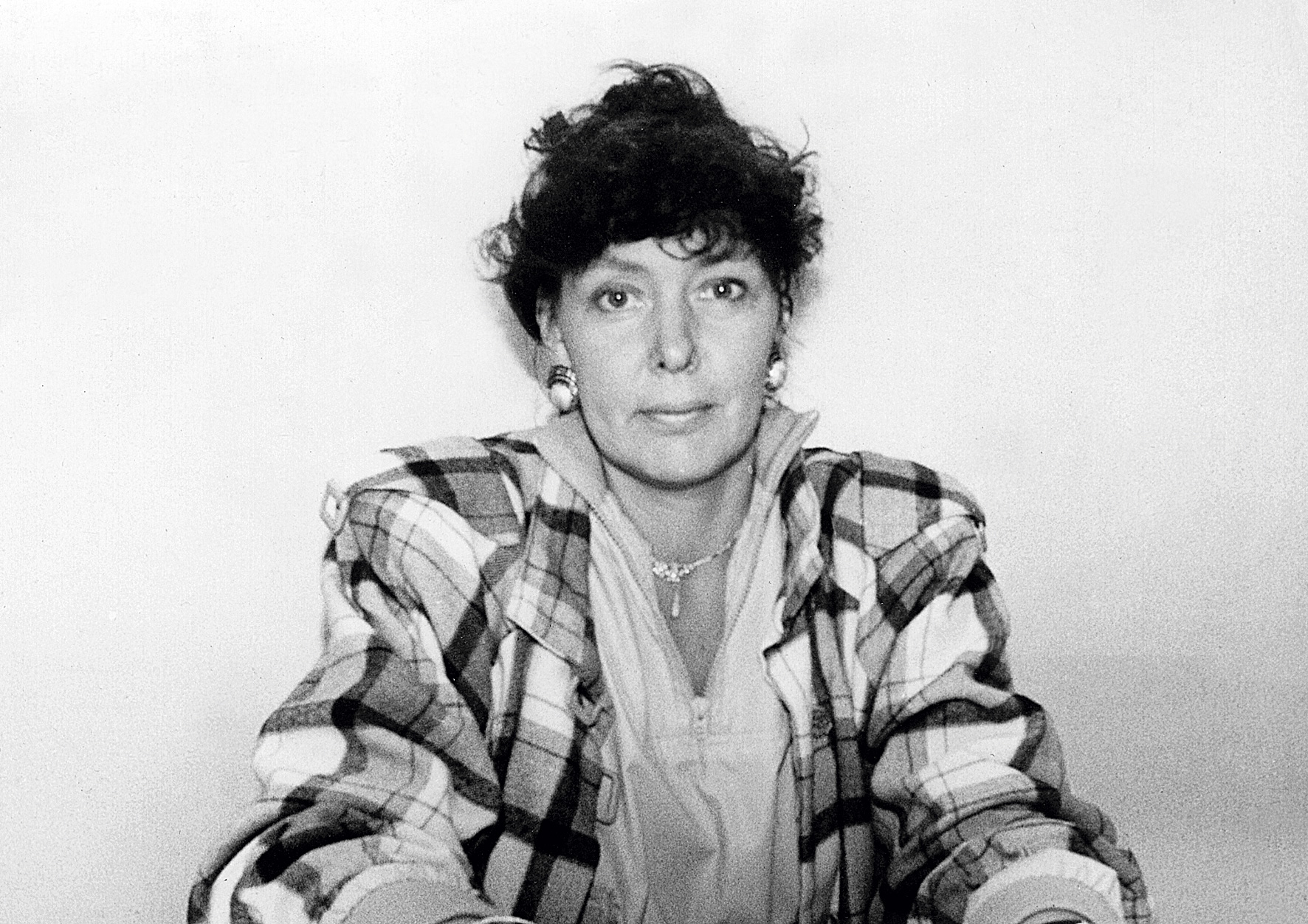

The Estonian writer and politician Maimu Berg (71) mesmerizes readers with her audacity in directly addressing some topics that are even seen as taboo.

As soon as Maimu entered the Estonian literary scene at the age of 42 with her dual novel Writers. Standing Lone on the Hill (Kirjutajad. Seisab üksi mäe peal, 1987), her writing felt exceptionally refreshing and somehow foreign. Reading the short stories and literary fairy tales in her prose collection Bygones (On läinud, 1991), it was clear – this author can capably flirt with open-mindedness! It was rare among Estonian authors at the time: female characters confessing their body complexes, analyzing their sexuality and aging, and admitting the existence of forbidden lusts and addictive relationships.

Self-irony is especially impactful when a story is conveyed in the first-person, and Maimu practices this regularly. She says that striptease is a piece of cake compared with the way a writer can emotionally expose him- or herself: “I’ve written poetry about the feelings or occurrences that I take from life, leaving the impression that I’ve personally gone through all of it.”

Maimu tackled femininity and national identity in her novel I Loved a Russian (Ma armastasin venelast, 1994), which has been translated into five languages. Complex human relationships and the topic of homeland are central in her modernist novel Away (Ära, 1999). She has also psychoanalytically portrayed women’s fears and desires in her prose collections I, Fashion Journalist (Mina, moeajakirjanik, 1996) and Forgotten People (Unustatud inimesed, 2007).

Beauty obligates

Maimu’s earliest memory is the fear she felt when standing on a chair, alone, in a glass-ceilinged photography studio at the age of 18 months: it was the first time she was away from her mother. Growing up in a very Estonian-minded family [i.e. those who resisted the attempts at large-scale Russification – Trans.], the future author began reading at the early age of four, and writing at five. Back then, Estonian families generally read a lot at home, since the only forms of domestic entertainment available were reading and listening to the radio.

Maimu’s interest in Finnish literature began very early on, thanks to reading Aleksis Kivi’s novel Seven Brothers (Seitsemän veljestä) cover-to-cover at the age of ten. Since she had a stay-at-home mother for several years (an unusual phenomenon in the ESSR), Berg received a plentiful amount of quality time: they went together to cafés, concerts, fashion studios… She also inherited her interest in music from her mother, and the pair sang opera duets at home.

In her books, Maimu has heavily addressed the topic of beauty and the pressure an attractive woman feels to be perfect in every sense. She acknowledges that beauty generally doesn’t make things easier for a person: “At least in the case of my characters, it usually serves as an obstacle or causes problems.”

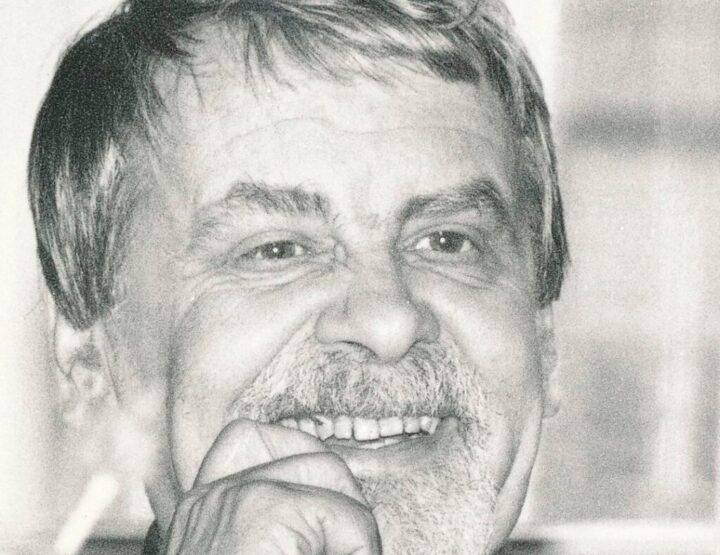

Berg met her first husband, the charismatic psychiatrist Vaino Vahing, who later became a prosaist and dramaturg, while studying Estonian philology at the University of Tartu. To this day, stories are still told of the Vahings’ literary parlor, the golden days of which crescendoed in the early 1970s. Every Tuesday night, Maimu and Vaino’s apartment would be crowded with actors and intellectuals discussing theater, literature, and people. “We exchanged thoughts about things we’d read, keeping up a scholarly conversation. If someone had acquired any materials from abroad, then we’d listen attentively, but there was also just simple banter, too,” Berg recalls.

Several major Estonian cultural personalities – Peeter Tulviste, Ingo Normet, Mati Unt, Hando Runnel, Jaan Kaplinski, Joel Sang, Juhan Viiding, Andres Ehin, Madis Kõiv, and Paul-Eerik Rummo – frequented the Vahings’ parlor. Inevitably, a KGB informant or two would occasionally end up in the mix. Maimu was working at the University of Tartu Library and acquired an extensive knowledge of literature: she possessed a wide array of interesting facts with which to surprise her guests.

A passion for the theater was another link connecting the legendary couple Maimu and Vaino Vahing. It was in their parlor that life was breathed into new developments in Tartu theater during the 1970s, and the pair attended performances at preeminent Russian theaters in the only metropolises accessible to them at the time: Moscow and Leningrad.

Maimu has also written her own plays: the Vilde Theater has staged her dramas To Europe, To Europe (which starred the couple’s amateur actress daughter, now European Court of Human Rights Judge Julia Laffranque) and Russian Roulette. Several modern Finnish dramas have also been staged in Estonia thanks to Berg’s translations, e.g. Jouko Turkka’s Connecting People, Lea Klemola’s Kokkola, and Reko Lundán’s Teillä ei ollut nimiä. Her translation of the latter play earned her the 2008 Aleksander Kurtna Award. Besides more than a dozen plays, Maimu has translated into her native Estonian Päivi Setälä’s books on the history of women’s roles in the Middle Ages, antiquity, and the Renaissance; Martti Turtola’s historical work on Estonia’s President Konstantin Päts, as well as his General Johan Laidoner and the Fall of the Republic of Estonia 1939–1940; and Laila Hirvisaari’s I, Catherine and We, Empress.

Boldly and busily

Estonians are well aware that the island of Saaremaa – the country’s largest – yields tough, strong, busy women. Maimu’s maternal roots also stretch to Saaremaa. One testament to her energy and vigor is the fact that when she received a little piece of ancestral Saaremaa coastal property through post-Soviet land reform, she decided to build a house there.

Maimu developed a close relationship with the world of beauty and fashion while working as an editor of the magazine Siluett. Her memoir The Fashion House (Moemaja) gives intimate details about the period. The publication’s editors would buy relatively recent issues of foreign fashion magazines from second-hand stores, thus getting an idea of Western fashion trends. Soviet censors allowed the printing of foreign fashion collages in magazines, so the editors used them to convey what styles were coming. While working at Siluett, Maimu also received her second degree, in journalism, from the University of Tartu.

Even though Maimu has written 13 books and is acclaimed both at home and abroad (her works have been translated into 11 languages), the author admits that she still feels like she ended up in literature by accident. One reason might be that she didn’t remain a freelancer, but did salaried work. After leaving Siluett, Maimu worked as a department editor at the literary magazine Keel ja kirjandus, and was the founder and first editor-in-chief of the magazine Elukiri, which is aimed at an elderly readership.

For 20 years, Maimu also worked at the Finnish Institute in Estonia, mediating cultural exchange. This period helped to cultivate the author’s close ties to the Finnish Writers’ Union, and naturally marked the beginning of her efforts to familiarize Estonian readers with Finnish writers and literature. Berg was made an honorary member of the Finnish Writers’ Union in 2010 and has received the Order of the White Rose of Finland, in addition to several literary awards. The Republic of Estonia has thanked her with the Order of the White Star, 5th Class.

Maimu was invited to join the world of politics mainly because of her bold opinion pieces. She has also published the collection of essays Dancing with My Late Father: Observations of Estonian Life (Tants lahkunud isaga: vaateid Eesti ellu, 2003). As a member of the Estonian Social Democratic Party, Berg has served as a Tallinn city councilor and a member of the Riigikogu (Estonian parliament). Having now left Estonian politics, Maimu asserts that life in Estonia is not easy for the elderly or large families.

Although Berg is retired, she still can’t seem to find enough time for her own writing, since she remains busy translating and writing media-commissioned pieces. The author also spends a fair amount of time traveling, primarily with her husband, who is a Finnish writer, and to visit her grandchildren in Strasbourg. No doubt it is partly thanks to Maimu that the two boys are fluent in Estonian – as is their French father – despite living so far away.

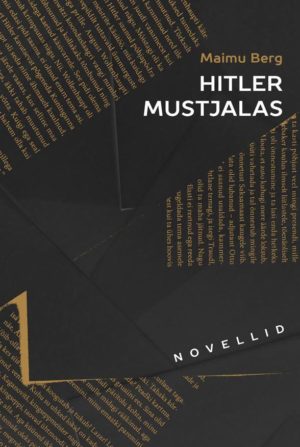

Berg’s most recent short-story collection, Hitler in Mustjala (Hitler Mustjalas, 2016), was nominated for the Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Award for Literature shortly after being published. It received the Friedebert Tuglas Short Story Award and the August Gailit Short Story Award.

In many of her works, Maimu Berg, who has ample opportunity to compare circumstances in her native country with those customary elsewhere in Europe, has focused on the fact that the elderly in Estonia are often shunned or self-isolated. Low self-esteem is often the culprit: Oh, what good am I anymore… Maimu splices self-confidence with wit, and through her writing and its deep sincerity, she endeavors to boost this self-confidence in many of her (female) readers. Hopefully, she will continue doing so in the future.

Aita Kivi (1954) is a writer and editor of the 93-year-old Estonian women’s magazine Estonian Woman (Eesti Naine).