On New Year’s Eve a man straggles his way through Stockholm. Although he has been living in the city for quite some time, the narrator feels like a complete stranger. Everything and everyone seems hostile to him. He hears people screaming and sees them flashing their teeth, as he eventually spots a light coming out of a house. He enters the house at about a quarter to midnight, in hope of warmth and company, not knowing that time and space follow their very own rules in there. The man is the alter ego of Karl Ristikivi, author of the novel Hingede öö or The Night of Souls, one of Estonian Literature’s most enigmatic classics.

“With a few clear, almost harsh sentences, Ristikivi not only sketches the exact picture of an inhospitable city in which an irritable mood can turn violent at any time, but also of the complicated and contradictory inner life of a lonely, deeply insecure person”, wrote the German critic Nicole Henneberg, who was particularly impressed by the magnificent opening of the novel.

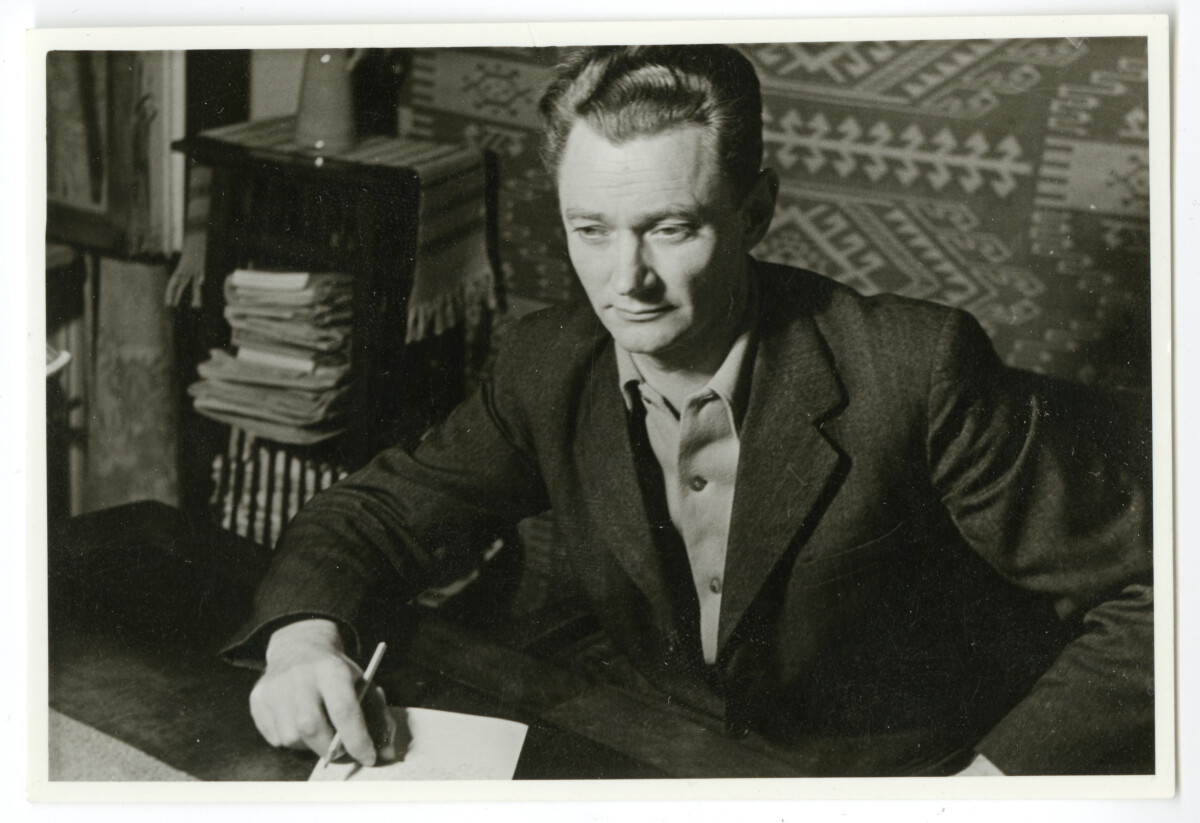

Born in 1912 to an unmarried maid in western Estonia, Karl Ristikivi began writing after moving to Tallinn, where he studied and later worked as a clerk. He debuted in the 1930s with a series of children’s books and rose to fame with his “Tallinn Trilogy”, which depicts the urbanization process of Estonia from three different perspectives. Then, however, came the occupation of Estonia, first by Nazi Germany and later by the Soviet Union, which forced Ristikivi to leave his homeland and flee to Sweden via Finland. Exile threw the writer into a crisis and years of literary silence, which ended in 1953 with the publication of his most famous work, The Night of Souls. This surrealist novel, which was strongly influenced by existentialist philosophy, stands out in the oeuvre of the multifaceted author Ristikivi and in Estonian literature in general.

After entering “The House of the Dead Man”, as the first of the three parts of the novel is named, Ristikivi’s narrator finds himself in what appears to be a concert. To his great surprise, the singer, a young woman named Bella, comes up to him and leads him to a small, windowless room. There he is introduced to a young, apparently terminally ill man named Olle, who shares his intimate memories and dreams with the narrator. But this is only the beginning of a myriad of absurd situations. Later, the narrator takes part in a banquet, gets a tour through an art exhibition consisting of exactly one picture, and listens to the argumentative pirouettes of a diabolic pastor, just to name a few examples. What all of these slightly uncanny situations have in common, is that everybody in the house seems to know the narrator.

Although the narrator gladly plays along and most people have a benevolent attitude toward him, his extraordinary solitude is tangible throughout the entire novel. As the German critic Paul Stoop noted in his review of the German translation of the book, Die Nacht der Seelen (published in 2019), the foreignness of the exilé is a core theme of the novel, but in contrast to other literature written in exile, “it is not about the coldness of mainstream society and hard-hearted bureaucracy. The feeling of strangeness is self-generated.” Due to its radical modernity, The Night of Souls drew a wide range of comparisons, from Kafka and Lewis Carroll to Hermann Hesse. Alluding to the novel’s characteristic mixture of luxury, anxiety, and foreignness, Jan Brachmann, another German critic who was likewise mesmerized by the novel, even saw similarities to Alain Resnais’s avant-garde movie Last Year at Marienbad, which came out approximately ten years later, 1961.

Similar to Dorothy L. Sayers, Ristikivi heads each chapter of the first section of the book with epigraphs by T.S. Eliot, Lewis Carroll, Oscar Wilde, John Bunyan, A.E. Housman, Walt Whitman, and Edgar Allan Poe. What’s more, just like his favorite writer of detective novels, Ristikivi was also strongly drawn towards darkness. As the narrator stands in the art exhibition, the light suddenly goes out. After the light returns, he tries to leave the room and finds himself in the very picture he was looking at, one of the most impressive scenes of the entire book. Eventually, he leaves the room and moves on into a theater auditorium, where he witnesses a play that he himself had written (but never published) a long time ago and which culminates in a praise of darkness.

The stylistic proximity to detective novels becomes quite evident at the point the narrator is included in a police investigation. It seems a crime occurred while the light was off, but the true events in that brief moment of darkness remain unclear. The narrator continues his journey, descending into the very heart of the house, where he is confronted with death, both in an abstract and in a concrete sense. Significantly enough, the first section of the book ends in front of a door bearing the words: NO ENTRY FOR FOREIGNERS!

The second part of the book consists of a letter to an imaginary reader named Agnes Rohumaa. The letter is an alienation device, reminding the audience that the novel is pure fiction. But the letter, which is a response to a critical letter by the same imaginary reader, can also be understood as an artistic manifesto. Through the letter, Ristikivi gives certain clues as to how he himself interprets the book, which he is in the process of writing, and that he dubs a travelogue or realistic tale. A confused world that has become meaningless can no longer be described in linear terms, the letter says, and literary figures now also go their own way.

Although the novel is full of arcane symbols and fairly complex in terms of its structure, it reads rather swiftly. This is partly due to the straightforward and timeless language Ristikivi uses in the text, but it is also due to the superb subversive humor that has particularly enthralled German critics. The absurdity of the narrator’s encounters with other people in the house is pushed to an extreme, they suddenly disappear, get new names, play different roles, and even change their appearance, but through this extreme absurdity, Ristikivi exposes much hypocrisy in human interaction. Or as Nicole Henneberg remarks: “It could be a depressing scenario. But Ristikivi has written an elegant, fun novel, full of magic tricks and obstinacy. An exile novel whose literary hero is far too clever to give up:”

The autobiographical background becomes evident in the chapters following the author’s letter-manifesto, in which he essentially relives the flight from his home country. Tired and numb, the narrator enters a small room divided into two pieces by a counter and a wire fence. The signs on the wall are written in German, French, Polish, and Latvian. A man sitting on the other side of the counter wants to see the narrator’s documents, but he has none and there is no way back for him. The narrator thus gets chased off by a man wearing the field-gray uniform of the Wehrmacht and ends up in a waiting room, before he is examined by a doctor. After telling the doctor about his dreams, the doctor tells him that he doesn’t like his dreams and that he shouldn’t be sleeping at all.

The third part of the book, called “The Seven Witnesses” culminates in a trial that has a certain reminiscence of Kafka, but Ristikivi professed that he wasn’t aware of Kafka’s work while writing his novel. One after another, seven witnesses are questioned about the seven deadly sins, but the manipulative judge, who is further incited by the audience, treats them as if they were accused themselves. The trial and the narrator’s journey end shortly after midnight, but the journey of the author continued on.

In the 50s and 60s, the writer and bachelor Karl Ristikivi, whose bread-and-butter job guaranteed a steady income, started to travel around Europe, partly to do research for his historical novels. Ristikivi had a vast knowledge of European history, and his works span many centuries. But after arriving in Sweden, Ristikivi never again wrote about Estonia. Perhaps, it was too painful for him. Karl Ristikivi died in 1977 and never returned to his homeland alive. His ashes were originally buried in Stockholm, but his urn was transferred to Estonia in 2017. It was only after the dissolution of the Soviet Union that Ristikivi would gain the status in his homeland that he had always deserved.

The Night of Souls was translated into Danish in 1993, and into Russian in 2009. More recent were the translations into German and Finnish, in 2019 and 2022 respectively, which both garnered considerable critical acclaim. Needless to say, Ristikivi’s writing and The Night of Souls in particular deserve a much wider distribution. Karl Ristikivi has written a unique and mesmerizing book, arguably the best exile novel in Estonian literature, and par excellence in world literature. But it is more than that: Ristikivi offers a very personal take on the human condition. Through him we learn that exile is perhaps the most extreme form of solitude.

**

Karl Ristikivi (1912-1977) was one of Estonia’s most prominent exile writers. He has published numerous historical novels, short prose, poetry, essays and children’s books. The surrealistic novel The Night of Souls is his most famous work.

Maximilian Murmann (b. 1987) is a translator of Estonian and Finnish literature.