‘And we are standing at the crossroads.

There are many aims and aspirations in our country, but the task of the young should be: when time is narrow and low, it must be expanded and adapted according to needs!

What makes circumstances better suited to the needs of people and nations, what drives and lifts people, is education. And our call is: M o r e c ulture! This is the first requirement of all liberating ideals and aspirations. M o r e E uropean culture!

Let us be Estonians, but also become Europeans!’

(Gustav Suits, 1905)

The quotation chosen as an epigraph is taken from the text The Aspirations of the Young. The text was published in mid-summer of 1905 in the collection with the meaningful title Noor Eesti I (Young Estonia).

The publication year of this album was the basis for celebrating the 100th anniversary of Young Estonia in 2005. Ignoring for the moment all nuances, this marked the starting point of aspirations of joining Europe, expressed in no uncertain terms. Ninety-nine years after the publication of that appeal, Estonia became a member of the European Union, and Estonians were finally declared Europeans according to all formal parameters. Some think we have been Europeans all along, but others do not agree and moreover see no reason to ever want to become Europeans. However, these issues are not our concern here.

The late President Lennart Meri considered the Young Estonia movement very important, and emphasised in 2000 that the jubilee must be celebrated widely and with great respect.

Marking the anniversary in spring 2005, however, was largely limited to literary circles. The nucleus of Young Estonia was after all made up of writers, and the group was primarily seen as a literary phenomenon throughout the 20th century, especially in the second half, during the Soviet occupation. This was a historically justified, albeit narrow, approach: the activity of the leaders of this group as writers and literary critics resulted in diverting Estonian literature from previous German-influenced didactic literature, national-romantic poetry and realistic village prose towards a wider range, seeking inspiration in neo-romanticism, modernist trends and urban literature. ‘Literature is art and thus its own purpose’, wrote Johannes Aavik in 1910. At that time this was certainly a ‘new glance at literature’, as he himself admitted.

Young Estonia was a cultural movement that had a considerable effect on early 20th century Estonian society. During that period, ideologies, foreign examples and leaders of the Estonian world of literature all changed. Noor-Eesti was the cultural movement of a young intelligentsia, which, more or less in the same way as in other countries (see e.g. Young Italy, Young Belgium, Young Germany, Young Finland, Young Turkey etc ), changed the paradigm of social and cultural life.

The nucleus of the Noor-Eesti group was composed of the illegal circles of grammar school students in Tartu that formed in 1902 and 1903, focusing on national literature and/or politics. One of those circles was headed by the future prominent poet Gustav Suits, who edited a literary almanac titled Kiired (Rays) with the aim of ‘promoting the best in Estonian literature’. Rays I was published in 1902, and the second and third parts in 1903; besides works by fledgling Estonian authors, these publications also accepted offerings from young aspiring Finnish writers. The fourth issue of Rays was delayed by censorship for over a year, and when it finally was allowed to come out, the editors decided to call it Noor-Eesti – Young Estonia. So, half-accidentally, the group got a name that is now firmly a part of Estonian history. Like all phenomena in history, Young Estonia has also been accompanied by myths, simplifications and lively polemics about its meaning. I will return to this issue at the end of the current article, after trying to give an overview of the phenomena and people on the basis of which the myth of Young Estonia was later formed.

Under that name, the group published four more issues by 1915: Noor-Eesti II in 1907, Noor-Eesti III in 1909, Noor-Eesti IV in 1912 and Noor-Eesti V in 1915. In 1910-1911 Gustav Suits and Bernard Linde also edited six issues of the Noor-Eesti magazine. The group-publishing house that initially worked half in secret was legalised in 1912, when permission was granted to establish the Estonian Writers’ Union, Noor-Eesti, which took over the publishing house of the same name. Noor-Eesti turned out to be the most vigorous of all the publishing houses, successfully operating in Tartu until it was nationalised by the Soviet authorities in 1940.

When we talk about Noor-Eesti, we have first of all in mind a small group of young people: writers who published these albums and magazines, artists who illustrated them, and other intellectuals, politicians, lawyers and natural scientists who gathered around the magazine Vaba Sõna (Free Word), issued by the publishing house Noor-Eesti between 1914 and 1916. The term nooreestlane (young Estonian) established itself at the same time, embracing all the readers-subscribers of the above-mentioned publications and supporters of the ideology propagated in them.

The Young Estonia movement was the creed of young people – the first movement in Estonia promoting openness to the world, freedom, democracy and individuality.

Their more general aim was to abandon the narrow national approach, or rather to try to get rid of the overpowering German and Russian influence on Estonian culture. Here, an encouraging example was provided by Finland, where various Estonian intellectuals studied (Suits, Aavik and Grünthal) and lived for longer periods (Friedebert Tuglas). Aino Kallas, a Finn, published a lot of translations of Estonian literature in Finland. This kind of Tartu-Helsinki axis operated until the end of WW I. Kallas herself married an Estonian, whereas Suits, Grünthal and Hella Murrik (Wuolijoki, published her work in the first albums) married Finns.

The other focal point, especially for the Noor-Eesti artists, was Paris. At that time the formula ‘they all have two homelands, the other being France’, was still valid among European intellectuals. Konrad Mägi, Nikolai Triik, Jaan Koort, Friedebert Tuglas and others reached Paris via Helsinki. Triik and Mägi, the main designers and illustrators of Noor-Eesti publications, later became the most prominent painters in Estonian art.

A powerful impetus for the movement was of course the 1905 revolution: many Young Estonians took part in this failed uprising and had to leave the country. Faith in democracy, faith in social justice and, above all, faith in freedom in its widest sense were badly shaken at the beginning of WW I. Noor-Eesti as a movement came to an end then, to be continued as an individualist proclamation of enjoyment in the literary group Siuru during the 1917 revolution. The real end of the Young Estonia spirit occurred in the Estonian War of Independence (1918-1920). After the war, a harsh and sober generation emerged in culture, and they valued nationalism and realism. Opposition to them emphasised the Young Estonians’ romantic idealism and mentality, so congenial to pre-war European modernism and turn-of-the-century intellectualism, aesthetics and irony. Young Estonia was quite a complicated phenomenon in the sense that it turned the entire Estonian culture towards Europe and, as sometimes spitefully claimed, engaged in ‘self-colonisation’.

Historically, the Young Estonian movement was also the beginning of Estonian urban culture, the birth of modernism in Estonian literature and culture. Within the framework of the Young Estonia movement, linguistic innovation, unique in the world, was carried out when Johannes Aavik forcefully and aggressively rearranged the morphology of the Estonian language, expanded the vocabulary, recommended certain dialectal words and loans from the Finnish, and created totally new words himself. ‘The tool first, then the book; language first, then literature!’ was his slogan through the first two decades of the 20th century. In correcting and adding to the language, he relied on the openly aesthetic principle, and talked directly and without embarrassment about the beauty of the language, which he felt had to be constantly kept in mind. Linguistic innovation caused a polemical reaction in society and not all Young Estonians always agreed with Aavik’s proposals. However, overall it was his professional work that considerably enhanced the rapid emergence of European linguistic and literary culture in Estonia.

Relations with the past

Estonian society has always been extremely small, and especially small, until the early 20th century, was the Estonian intelligentsia. The contribution and role of any single creative person has been much more substantial. Estonia passed through its national movement period, in which our national epic Kalevipoeg (Kalev’s Son) was published, in the second half of the 19th century. Its author, the intellectual and sceptical provincial doctor Fr. R. Kreutzwald, additionally published a large number of fairy tales, thus establishing a foundation for Estonian fiction (verse-form epics that imprecisely followed the folk song form, and folk tales reworked after the examples of contemporary German prose). Lydia Koidula’s passionate patriotic poetry was a tremendous inspiration to national poetry. The increasingly deeper Russification process during the last decades of the 19th century largely suppressed national enthusiasm and various central enterprises of the national movement came to an end. This atmosphere of oppression was broken up at the end of the 19th century by the Tartu nationally-minded circles who took over the paper Postimees and, at the turn of the century, awakened society to a new revival, known as the ‘Tartu Renaissance’. The national spirit was primarily carried by the newspaper editor Jaan Tõnisson, the pastor Villem Reiman, the schoolteacher Oskar Kallas and others. Under their leadership and financial help a new generation grew up, which founded Noor-Eesti. When the literary group later opposed themselves to these people, in the true fashion of classical patricides, this engendered yet another accusation against them of nihilism and of disrespect for continuity. This was, in fact, true, as the self-confident young people proudly declared that Estonian literature started with them, and they were prepared to acknowledge only Kristjan Jaak Peterson and Juhan Liiv. ‘Noor-Eesti – this is an accusation against our surroundings and our past!’ declared Tuglas in 1915. In the name of historical justice it must hereby be admitted that the young people of the next generation maligned the Young Estonians just as fiercely in the 1930s, brandishing the slogan of ‘closeness to life’.

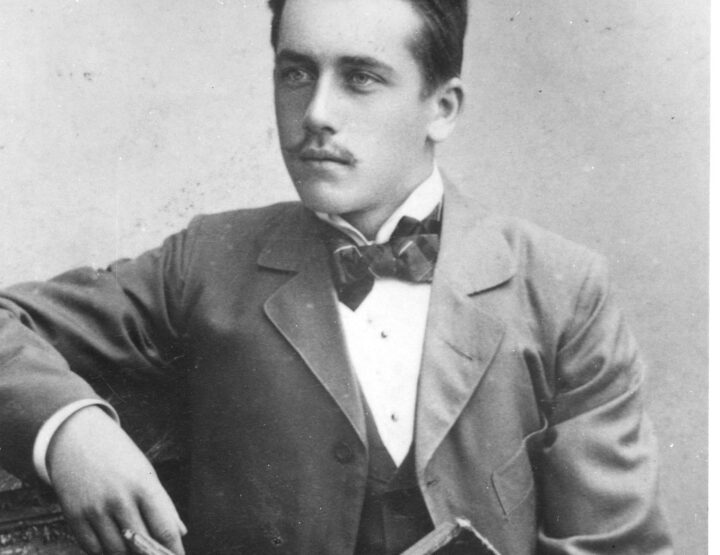

Gustav Suits and Friedebert Tuglas

During its heyday, the leader of Noor-Eesti was certainly Gustav Suits (1883-1956). This precocious idealist was, at the time, a highly ambitious and erudite young poet who worked as a language teacher in Finland during his school holidays and made contacts there that enabled him later to publish his first two books in Helsinki. He corresponded with two great idols of the Estonian young people – Juhani Aho and Georg Brandes. He was extremely popular in Estonia as a poet (his debut collection Elu tuli, The Fire of Life, 1905) and when he became Professor of Estonian and General Literature at Tartu University at the beginning of the Estonian Republic, many students confessed to have chosen the subject primarily because of Gustav Suits and his reputation as a poet. In his thirties he became somewhat resigned and very critical of himself and, as a consequence, published less in later years, both as a poet and a scholar. During the Young Estonia period, however, he was extremely prolific and enterprising. Left-wing in his views, he tried to combine individualism and socialism in his youth (his book Aims and Views, 1906). He was extremely open in his literary pursuits, and his extensive reading is evident in his research and criticism, especially in the works chosen for the movement’s publications.

Suits, as a poet, had considerable influence on the canon of Estonian poetry in the 20th century and had an impact on many prominent authors, from Betti Alver to Kalju Lepik.

Suits is also the author of an unfinished book on the history of Estonian literature (1953); his first attempt in that area occurred in 1908, while still a student at Helsinki University. It was Suits who wrote the overview Die estnische Literatur for the comprehensive world literature encyclopaedia Die Kultur der Gegenwart, published in Germany. In his overview, Suits regarded everything in Estonian literature before Young Estonia as an introduction. Gustav Suits was also active politically; he joined the party of socialists-revolutionaries after WW I and participated in the work of the Estonian foreign delegation in 1918. In his role as a professor of literature, Suits was an internationally acclaimed authority who was named an honorary doctor of Uppsala University and an academician of the Republic of Estonia.

Unlike the academically educated Suits, Friedebert Tuglas (1886-1971) was self-educated and even failed to finish grammar school during the 1905 revolution. He, too, had started writing at an early age and his literary interests during the radicalisation period of society intertwined with direct revolutionary activities. The seeming contradiction between the later image of the respectable literary figure and the young rebellious speaker at revolutionary gatherings is explained by the fact that Tuglas was always involved in all social issues. In his youth this was manifest in his revolutionary activities, in middle age he founded and edited literary magazines, and then he established the Estonian Writers’ Union and later headed it. Gustav Suits characterised him in the early 20th century in Tartu as ‘the local Jean Jacques’.

In 1903 and 1904 Tuglas published his first short stories. In 1905 he was a 19-year-old student at the Treffner private school who spent a great deal of time at secret meetings and gatherings, even joining the Russian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party, where he was a member of its lesser wing (the Mensheviks). In late 1905 he was arrested, and was freed from the Toompea prison on his 20th birthday on 3 March 1906. His subsequent exile lasted until spring 1917. Tuglas lived mostly in Helsinki, but also in Ahvenamaa and Paris, travelling around Europe, Italy and Spain. He visited Estonia several times with a forged passport. He wrote about his travels in his fascinating memoirs in 1940.

Tuglas was one of the leading Estonian modernist writers of the early 20th century. His short stories introduced stylistic and formal experiments, symbolism and impressionism to Estonian-language prose. ‘To create myths – this is the most beautiful thing’, he wrote.

The quintessence of Tuglas’s ‘aesthetic’ period was the ironic and impressionistic summer holiday novel Felix Ormusson (1915), which considerably expanded the existing overwhelmingly realistic tradition of novels. The Estonian literary canon was also tremendously enriched by Tuglas’s critical reviews and essays, which were later gathered into eight substantial volumes. Before WW II he was also one of the most widely translated Estonian writers, and was especially well known in Finland. This is evident in the active Tuglas Society in Finland, which introduces Estonian culture abroad.

Aino Kallas (1878-1956), born in Finland and married to an Estonian, published a lot of her work in the Young Estonia publications. Her originally Finnish-language books were translated by Gustav Suits and later mainly by Fr. Tuglas. Although through her husband Oskar Kallas she was a part of the circles centred on the daily Postimees and befriended the leading ideologues of the previous generation, such as Jaan Tõnisson and Juhan Luiga, her aesthetic aspirations harmonised with those of the younger generation. Young Estonia was the only literary group to which the internationally acclaimed Aino Kallas, extremely popular in inter-war Finland, ever acknowledged belonging. Her artistic experiments, which fell between realism and modernism, were similar to Tuglas’s work and they therefore readily translated and reviewed each other’s work. The first part of Aino Kallas’s diaries, written in Tartu, is a singular insight into the environment where Young Estonia was born and flourished. Her book Nuori Viro (Young Estonia, 1918, translated into Estonian by Tuglas) was the first place where the work of Young Estonians was comprehensibly and intelligently analysed.

The greatest classic of Estonian literature, Anton Hansen Tammsaare (1878-1940), also considered himself connected with Young Estonia. Tammsaare (then under the name of Anton Hansen) had already contributed to the album of the Rays, and also to the Young Estonia magazine. However, his major works appeared much later when he was living in Tallinn.

The reception of Young Estonia throughout the 20th century

The cultural impact of Young Estonia has had a lasting effect. In the early 20th century, Estonian culture managed to break out of the sphere of influence of German culture. The young intellectuals introduced Finnish and Scandinavian literature and conveyed news about other parts of Europe. Their literary output might have been fragmentary and quite small, but totally new perspectives opened up thanks to the poetry collections of Gustav Suits, Villem Grünthal and Juhan Liiv, just as the ‘the modernist breakthrough’ in prose was carried out by the student short stories of Tammsaare and Tuglas’s novel Felix Ormusson. Young Estonians played an equally essential role in meta-literature: reviews, literary essays and the biographies of various writers.

Besides Young Estonians, the most influential authors in literature at the time included Eduard Vilde, a determined realist who made fun of the Young Estonians’ modernist language; the great playwright August Kitzberg, who was the only writer of the older generation to favour the Young Estonians and taught them useful tricks of the publishing trade; and the poet Juhan Liiv, a mad genius whom the Young Estonians placed on a pedestal. The members of the movement had started young, and their literary heyday coincided with radical changes in society. This in turn has secured the survival of their ideas and artistic principles in the Estonian literary canon. The ideals of freedom and democracy of Young Estonians have never dimmed.

© ELM no 23, autumn 2006