How can one explain Nikolai Baturin’s works and creative identity to someone from a different and distant culture, when they are quite the mystery right here in Estonia? How can one cultivate interest in someone who hasn’t heard of or read the author by conjuring up a perceptible image, when in this culture that perceptible image is primarily an excuse for convenient ignorance and for eschewing reading?

A consensus has taken hold in Estonian literature: Baturin is a classic, a great, an exceptional author. In early 2016, on the eve of his 80th birthday, he received the Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Award for Lifetime Achievement in Literature. It was, perhaps, due to both the former and the latter circumstances that his newest novel The Mongols’ Dreamlike Invasion of Europe (Mongolite unenäoline invasioon Euroopasse, 2016) received greater media attention than several of his earlier and no less remarkable works published during the 21st century. And yet, how much discussion of his books takes place among cultural enthusiasts and the literati? How much talk of his entire literary treasury is there, of its merits and heroic protagonists? (Is it even possible to converse on the topic of literature today without treating heroism unironically? Baturin’s works present the possibility, but this tends to remain merely possible…)

Baturin doesn’t clamor to be noticed, doesn’t exhibit himself; he doesn’t blog, doesn’t “like”, doesn’t “share”, doesn’t collect important friends, doesn’t badmouth, doesn’t offend, doesn’t tweet about popular gossip, doesn’t fire off freedom-of-speech slogans, and doesn’t play the martyr of transgressiveness. In today’s culture, this means that even though he pens worthy literature, he doesn’t compete at any cost with his colleagues for attention, coverage, or a following. Baturin chose, ages ago, to restrain his ego in order to live in his creation, to refrain from making autobiographical revelations about himself as an individual so as to focus on the allegorical illumination of himself as a human being in his works of literature, to avoid popular and flashy modern-day topics in order to capture what transcends the ages in the temporal, and to use the temporal solely as a necessary switch or a launching pad, if at all. The “Avarilm” (1) of Baturin’s works, as he calls it, is above all mythical, magical, and archetypal, even in the precision of its socio-ecological details; his prose is poetic and has become increasingly elliptical. This isn’t easy for a literary reviewer to handle, given today’s tilt towards “critical realism”.

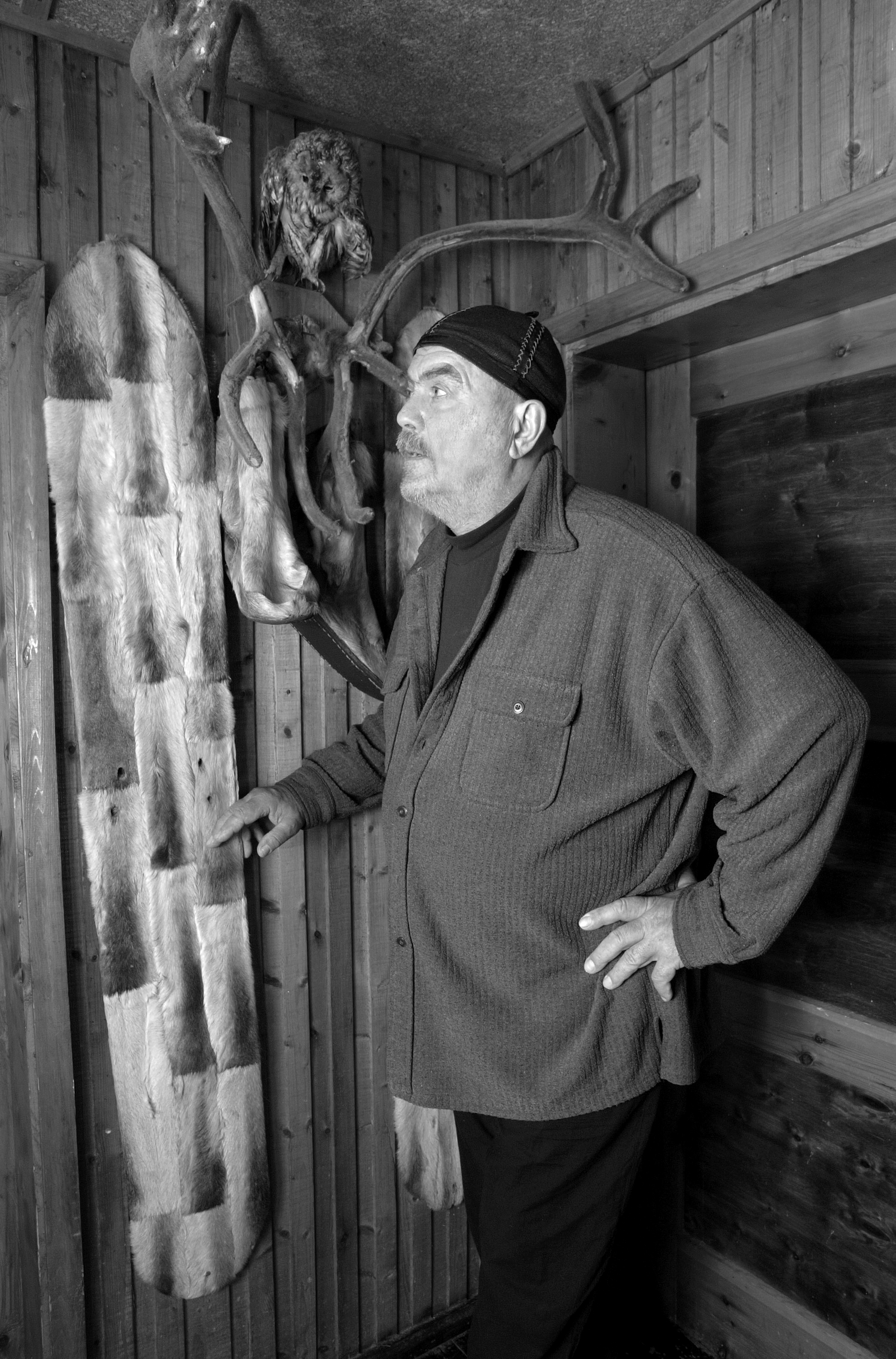

Or is this even a modern problem? It’s easy to blame the impatience and superficiality of the digital age for this alienation, but as the writer and translator Aivo Lõhmus (1950–2005) wrote twenty years ago: “Over the years, time and again, a book that somehow seemed unapproachable against the backdrop of contemporary Estonian literature emerged from the deep nothingness of the Siberian wilds; from the sweeping boreal forests; from the endless unpopulated expanses. And they remain unapproachable today – so unusual and extraordinary are all of Baturin’s works in the context of Estonian literature.”(2) Sixteen years before that, Lõhmus also wrote: “Nikolai Baturin, who has now come to publish his tenth book (Somersault Stories (Tirelilood), Tallinn: Eesti Raamat, 1980), is, to me, a slightly mystical individual to this day. It is difficult for me to vividly imagine a man who spends two-thirds of the year somewhere far away in the virgin Siberian forests, killing wild animals and skinning them for the benefit of Soviet industry, and who spends one-third of the year writing literature in Estonia, for the Estonian people; and who furthermore writes poetry in the Mulgi dialect. A man who uses the Estonian language so extravagantly in his prose that it makes even much-seen and much-read reviewers shake their heads, at a loss.”(3) Aivo Lõhmus, one of the most sensitive (and responsible) evaluators of Baturin’s writing, made remarkable mental and spiritual efforts to overcome the alienation, and at the same time was not blinded by Baturin’s exceptionality. Rather, through his precise critical remarks, he helped the writer himself to see the paths for delving into topics more clearly. Yet wasn’t it confounding? Someone who thinks in their local dialect when the West is semi-secretly being ravenously consumed all around him, who flees to the taiga when the KuKu Club (4) and kitchen parties emerge as hubs for the artistic elite, who readily embarks for Siberia when so many were relieved to be set free from there?

Baturin, whose 1968 debut Underground Lakes (Maa-alused järved) was published in a boxed set of short poetry collections, did also frequent artists’ studios. He may have ended up playing the role of le sauvage noble (5), something he enjoyed excessively at first (a fair amount of preening can be found in his early writing, both in terms of its roughness and cultivated qualities); however, it is worth noting that by remaining in the literary world, his mysteriousness to the understanding critic also grows. By facing literature, Baturin learned to be himself to an even greater extent: cultivating “literature” less, inhabiting the written word more deeply, and exploring his Avarilm within language itself. Baturin did not shift from poetry to prose, but rather into prose with poetry: he became increasingly bardic in his essays, short stories, and novels. Dramatic experiments were not fleeting tangents, but rather new, fruitful conquests of his poetry-prose. Colonies started supplying resources to the fatherland: in Baturin’s later novels, narration often bursts into poetry or song, into a dramatic dialogue, into something entirely beyond genre. The author doesn’t have the patience to stick to the tiny, restrained Nordic style of storytelling; he has a perpetual need to magnify language into capital first letters or into full caps, to wander in a dreamlike haze of cursive, or pop off ellipses on a hunt for who-knows-what-kind of imagined life-form. And time and again, amid the fireworks of stylistic excesses, there breaks out a silence; a pause. This shock wave of rapid withdrawal stuns the reader into thinking for him- or herself. Not all recover from the blow, and many discontinue reading…

Nevertheless, one of Baturin’s works that is known and read more widely, and is translated, studied, and quoted from time to time to this day is his 1989 novel The Heart of the Bear (Karu süda). The complicated story of a man’s search for himself deep in a boreal forest arose from Baturin’s own years as a trapper. It is an astonishing achievement of harmony between the perception of nature and linguistic mastery, between boreal crispness and exotic passion, between magical realism and realistic human ardor. After being published, the book became a gateway to remote places for many young anthropologists, and was also a gateway to intimacy for the author himself. Its protagonist Nika was Baturin’s most thoroughly cognizant avatar to date, and variations of the character took the stage in several of Baturin’s later novels: as Nikas in his childhood mystery Timid Nikas, the Comber of Lions’ Manes (Kartlik Nikas, lõvilakkade kammija, 1993), as the nerd-turned-superhero/oil magnate Nikyas Bigart in The Centaur (Kentaur, 2003), which won the 2002 Estonian Novel Competition, as the ill-fated captain and commander Nikolas Batrian in The Fern in the Stone (Sõnajalg kivis, 2006), and again as a seafaring passenger in the form of Nikodemes of Parnassos in The Flying Dutchwoman (Lendav Hollandlanna, 2012)… And although the events, characters, settings, and accentuations in these novels are very much unalike, the core is similar: impatience with common happiness and true happiness in suffering, the courage to face life and the lack of fear of death, a sense of the unknown and the opportunity for impossibility.

This bravado of big words and ponderous topics easily threatens to make the writing seem hollow and kitschy, but Baturin hurtles into the style’s lofty reaches from a foundation of vast personal experience: he has lived his own Avarilm on the taiga, in primeval forests, and on the ocean. One can believe that he has lived it in love, as well. Not to mention sound, which is another tremendous dimension of his writing: Baturin has acknowledged that he once dreamed of becoming a composer. The intense sensory nature of Baturin’s writing, and especially its musicality are proof that he has accomplished this dream in his own manner.

At the same time, readers tangled up in everyday troubles may have difficulty identifying with Baturin’s epic Übermenschen. And yet, the most fantastic world conquerors of his books are balanced by parallel characters: the mild, frail, gentle-minded youth who embodies the protagonist’s conscience. Has recent Estonian literature seen a more delicately sensitive short story than Baturin’s “The Window to a Yard With a Spring” (“Aken allikaga aeda”), which appeared in the May 2015 edition of the literary magazine Looming? In it, Master Immortell, a “plant-man with bird knees” who is living out his twilight days in a nursing home, is confronted by memories from childhood and calls out for his dear sister, seeking genuine and direct human proximity, which is perhaps life’s greatest mystery and opportunity for the impossible.

Baturin would not know himself if he did not know and appreciate the Other. A literary expert who possesses a late-20th-century academic education might accuse Baturin of colonialism or sexism after a cursory reading of his works, but a deeper reading reveals the author’s respect for indigenous cultures and old customs, for the honoring of various religious backgrounds, and most of all for his strong and self-aware female figures. All of these motifs stand straightforwardly and recognizably in the foreground of Baturin’s latest novel, The Mongols’ Dreamlike Invasion of Europe. Although the book’s plot is tied to the unexpected termination of Genghis Khan’s conquests in Europe, it is only conditionally a historical novel. Above all, it is an allegory of the clash of civilizations, an exaltation of the desire for understanding that arises alongside the urge to conquer, and which ultimately conquers that urge. Even while addressing distant ages in a poetic way, it is an insightful message for the troubled modern day. And didn’t those messages exist even earlier? At their allegorical hearts, Baturin’s works Caught in a Vicious Circle (Ringi vangid, 1996), Apocalypse Anno Domini (Apokalüpsis Anno Domini, 1997), the aforementioned Centaur and The Fern in the Stone, but also The Path of the Dolphins (Delfiinide tee, 2009), possess a humanist concern about both inner calcification and humanity having arrived at the brink of ecological catastrophe.

It may be true that only readers familiar with the unique aspects of Baturin’s poetics found in his earlier and “more expressively-written” full-length novels (The Heart of the Bear, Timid Nikas, the Comber of Lions’ Manes and The Centaur) can find affinity with his later works, which abound in pauses for thought and allegory. At the same time, there are also those who feel the urge to embark upon explorations of his heftier novels only after enjoying the author’s thinner (in terms of volume, but not necessarily content) works. There are readers who are intimidated by fragmentation and doubt the existence of connections within his works: based on personal conversations I’ve had with Baturin, I can assure these people that, in his mind, the works are assembled finely and meticulously. It is marvelous how he can speak about what he has written by heart and for hours on end, not forgetting even the slightest detail. Thus, in addition to everything else (or perhaps foremost), Baturin is a great storyteller.

With its extensive linguistic scope, its myriad of dialectal speech and neologisms, and its plays on words and names, Baturin’s writing poses an extremely difficult challenge for translators. Few have had the courage to accept this challenge. Even so, further opportunities for the impossible may lie in going for it: chances are that a translation of his work will expand and enrich a much larger literary language, that a reclusive writer hailing from a peripheral culture might turn out to tell tales and conjure poetic Avarilmad – broad worlds – to which people all across a troubled and fractured world can relate. It is in these opportunities for the impossible that literature’s lasting magic can be found.

(1) A play on words from the Estonian compound word for “world” – maailm (land+world/weather). Here, Baturin splices intoit the Estonian word for “broad/spacious”(avar), and in doing so opens up a realmof not only geographical, sub-oceanic, and cosmic expanses, but also of magical possibilities in the unknown and the ineffable.

(2) Included in the collection Power and Shadow (Võim ja vari), Ilmamaa 2002, p 237

(3) Ibid., p 221.

(4) KuKu Club is a legendary artists’ haunt in central Tallinn.

(5) “the savage noble” (French)

Berk Vaher (1975) is an author and literary critic. He has written four short story collections and the novel The Epic Story (Lugulaul, 2002), which is regarded as one of the most outstanding works of postmodernist Estonian literature. Vaher also spends his time writing music reviews and as a DJ.