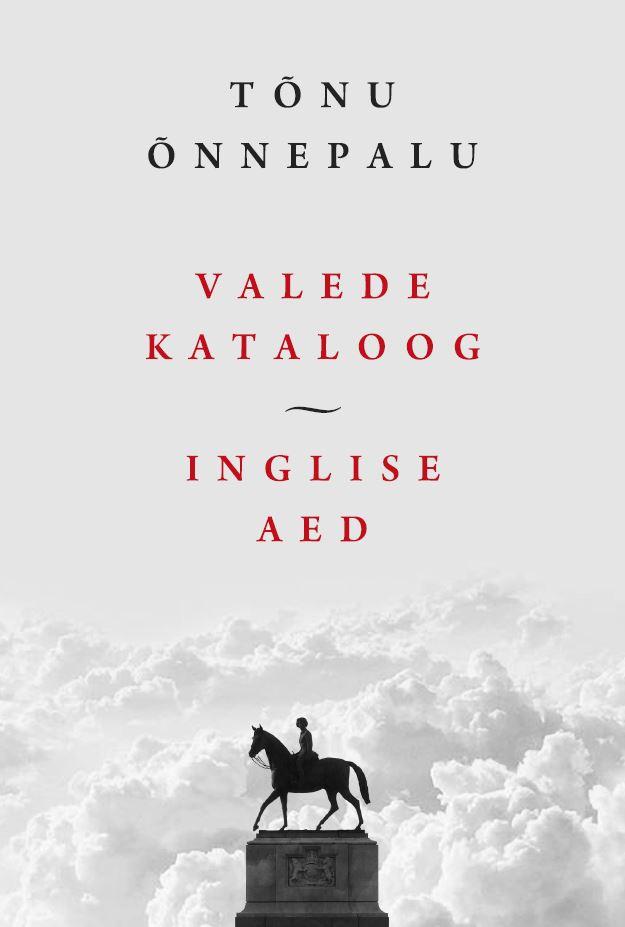

Tõnu Õnnepalu, Valede kataloog / inglise aed (Catalogue of Lies / English Garden)

Tallinn, Eesti Keele Sihtasutus, 2017. 392 pp

ISBN 9789949604289

When Tõnu Õnnepalu’s 1993 novel Border State (Piiririik) was published under the pen name Emil Tode, bringing gay sensibility to Estonian mainstream literature, it would have seemed quite a leap that its author would be considered one of Estonia’s foremost conservative thinkers a quarter century later. It shows the long way Estonian society has progressed in this short time. So, it only seems right that two of the reoccurring topics of Õnnepalu’s works, many of which are reassuringly similar and sparkle in a subdued way, are changing times and reluctance to change.

The first part of Õnnepalu’s latest work Catalogue of Lies / English Garden (Valede kataloog / Inglise aed, 2017), a collection of musings from spring and summer 2017, was seemingly inspired by life in Õnnepalu’s home on the island of Hiiumaa, while the second took shape during his three weeks’ stay in a village for the super-rich near England’s Windsor Castle. In addition to the author’s two traditional topics, the book ponders God, love, depression, the roots and future of capitalism, and outdoor work, mostly of a horticultural nature. The latter of these starts with planting season in Catalogue of Lies, and ends with the harvesting of cucumbers, potatoes, and tomatoes in the book’s afterword, “August”.

Catalogue of Lies derives its name from the author’s belief that “To live is to lie. Death ends lies and reveals the truth.” Thus, Õnnepalu’s intention is to record a catalogue of lies in his life, something akin to “dear faces in a photo album”.

While Catalogue of Lies focuses mainly on personal issues and on life in Estonia, with world events receding to the background, English Garden takes a more global approach. The author’s conclusions are grim in both cases. People are tired of liberal capitalism and the establishment has nothing to offer, but neither does the far-right or communism: both can provide only temporary hope, making the inevitable reckoning that much worse.

As always, Õnnepalu’s sentences are clear, his thoughts poetic and sometimes mischievous. Forbidden love is the only kind of love, in his words, because “unforbidden love is just marriage.” “If there really were a government that wanted peace, not war, it should first prohibit all ideas, i.e. everything human.”

Erik Aru (1978) is an Estonian journalist who has been writing literary criticism mostly for Eesti Päevaleht since 2010. He is also a PhD student in economics at University of Tartu.