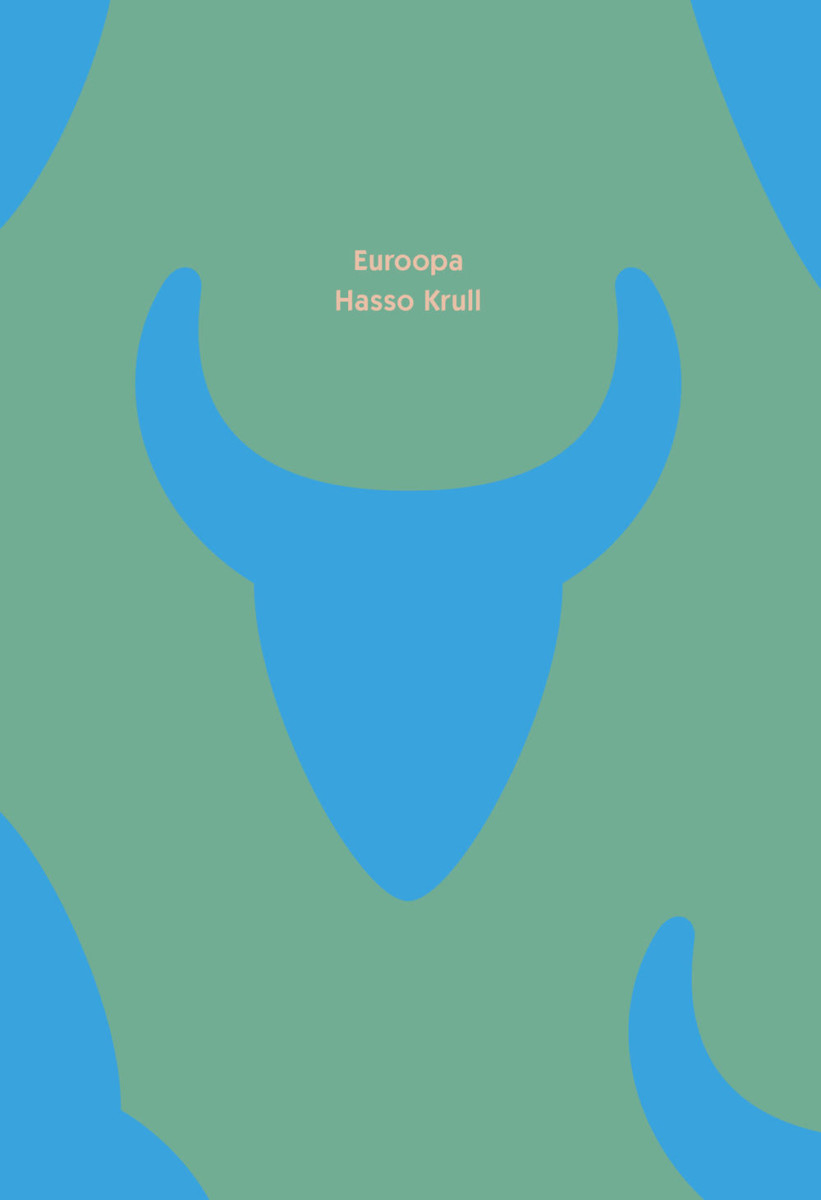

Kaksikhammas 2018, 92 pp.

ISBN 9789949999125

Hasso Krull’s poetry collection Euroopa (Europe) becomes steadily denser, more bottomless, and intricate with every reading – as if recalling something one can no longer remember, but is also impossible to fully forget. Europe weaves classical Ancient Greek mythology with post-colonial European angst, the steady decline of Christian culture, European progressiveness, the neoliberal cult of money, and modern-day ecological catastrophe. All of this is accompanied by well-structured metaphors, the seeming simplicity and frankness of Krull’s poetry, as well as the fluid presentation of motifs and their interconnectedness. The scope of Krull’s perspective that emerges in Europe appears dizzying to our ever-narrowing modern-day mindset, but also seems that much more relevant.

The fact that Krull turns occasionally to ancient mythology and other times to folklore when addressing the contemporary era points to his belief that we live not in a time of changes, but of repetition. Everything we encounter is composed of certain variations of the past; of recurring patterns that even encompass progressivism and the will to break free of that repetition. This resurfacing of patterns is based not in a linear historical continuity which is manifested in perpetually penning new stories based on the ones that came before, but rather in mythological circularity: retelling the very same story over and over again, but always in a strikingly different way. Mythological thinking is not, one might add, a thing of the past, but belongs right here to our most mundane of present affairs, thus allowing us to observe such events in a greater and more meaningful scope – one that nevertheless remains direct and individual. Mythologizing the present requires making painstaking efforts towards recollecting – tracing repetitive patterns despite impeding historical traumas, self-serving tendencies that may lead one astray, and dystopian impressions of the imminent future that foster a sense of powerlessness. “Is this indeed the pattern / of change? Is that where fortune awaits?” (p. 77) Krull suggests, with a note of hope in the last quarter of his collection, addressing the belief that Estonia has removed itself from the troubles Europe is currently facing. A response is given only a few pages later as Krull returns to the start; to what has once already been: “This terrain is somehow familiar, / as if I’ve been here before, though / I haven’t – perhaps only in dreams? But in what / dream was that?” (p. 81)

In Krull’s view, Europe is akin to a riddle that will ultimately never be solved because its solution would mean casting the riddle itself aside. It would mean uprooting Europe, and ourselves along with it, for good. “Every question is already old,” he writes, guiding us closer to Europe’s essence. “We heard it just yesterday, the day before; / we knew the answer but have forgotten it,” (p. 12) after which we are tasked with remembering – and, why not, interpreting – Europe once again. The dream itself is introduced shortly after, because like the riddle, the dream also lacks a final solution or an interpretation that elucidates all: “What a dream – it cannot be / watched, only told patiently and / at length; told until / the storyteller recognizes them self.” (p. 17)

The Europe Krull describes may indeed be taken as a dream, the telling and recollection of which is ever more pertinent and necessary with each passing day. It tells us something about ourselves – something that has long been impossible to avoid. This is also the case with Krull’s collection, the impetus for writing, which did not derive from an urge to portray Europe and its mythological origins, but rather the challenges the continent faces today.