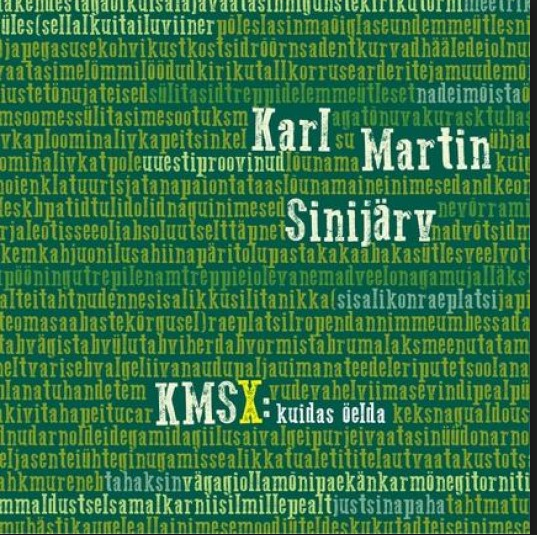

Karl Martin Sinijärv, KMSX: Kuidas öelda (KMSX: How to Say)

Tallinn, Näo Kirik, 2016. 96 pp

ISBN: 9789949980901

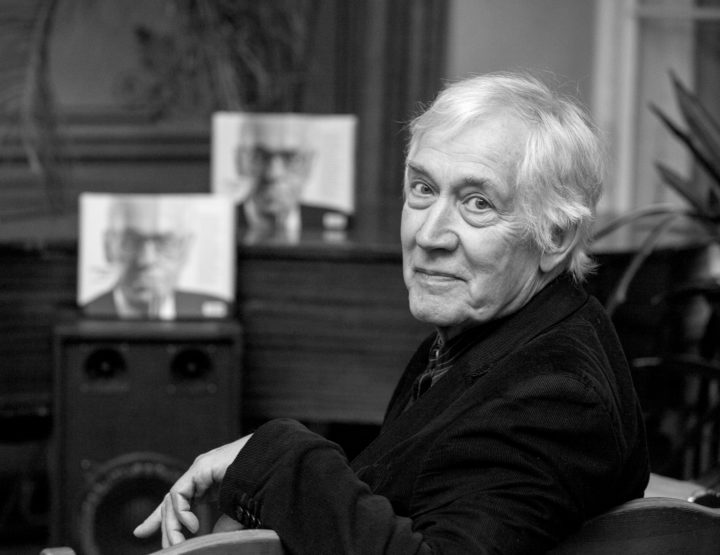

Karl Martin Sinijärv (1971, KMS) has been a presence in Estonian poetry for a good 30 years. Or, to be more exact, poetry has found its place in him. A unique, one-of-a-kind linguistic instinct has revealed itself in Sinijärv. Another Estonian poet who possessed this skill was the literary classic Artur Alliksaar (1923–1966), who grasped the Estonian language for all it is. Who was a magician. The measure of a language’s vitality is indeed the flutter in its peripheries; the manner, in which its poetry lives and breathes. Yet, Alliksaar lived in a difficult time, and the space for his breathing and expression was very narrow.

Alliksaar handed off the baton to one of the all-time greatest tamers of the Estonian language – Andres Ehin (1940–2011). On occasion, I’ve wondered whether it’s correct to call him a surrealist (which also applies to the greatest-ever exile-Estonian linguistic experimenter Ilmar Laaban (1921–2000)). They are alchemists of language in their own distinct ways; the unconscious realm in which they rollick is a deeper layer of wild, natural language that exists only as possibility.

One important ability that comes with this fluency in language is a sense for form; a naturalness, with which the authors have created even their most complex poetic meters, games, and structures. Other notable Estonian masters of this have been Ain Kaalep (1926) and Mati Soomre (1944–2015), the latter of whom even managed to translate into Estonian Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark (for a while, I wondered whether it really was a translation, or if it was actually some kind of a mathematic-linguistic game). This kind of formulaic capability must be demanded of translators of poetry from time to time, although in no way would I spurn Tõnu Õnnepalu’s (1962) free-form translations of Baudelaire, either.

Just as import as proficiency in form is the ability and capability to create new language or to warp that linguistic world to your own whims, no matter whether this means syntax or semantics or grammar, word form or –creation. It’s an ability as incredible as invoking rain from the sky with a mere glance.

Estonia can’t be home to many of these types of people, of course. And right now, we have exactly one: Karl Martin Sinijärv. He is the only active Estonian writer today, who I believe is capable of producing nearly every form of poetry in the Estonian language. On top of that, it’s a piece of cake for him to pull a new word or linguistic mutation out of thin air. Thus, he is a national treasure and should be placed under heritage protection! You may take it as a joke, but that’s not how I meant it – I say it in all seriousness.

This impressive level of competence naturally places obstacles before translators – just try to create a new expression or word in your own language in a way that it’s exactly as pure and acute. You’d have to be a real genius. Luckily, KMS’ works are extensive enough, sprawling from one end of style and form to the other, so there are texts aplenty that can be molded into translation.

Just like some of KMS’ earlier works (such as my personal favorite, Neli sada keelt (Four Hundred Languages: Strong Estonian Lager, 1997), which is partially English-language and was written in the US), KMSX: kuidas öelda is eclectic. He has more consistent collections, but this year’s work is colorful and intriguing – it encompasses slight formulaic bizarreness, punctiliously-penned love poetry, almost patriotic verse, poetic-apostolic sermonizing on par with that of poetess Betty Alver (1906–1989), small-scale absurdity (a series of mini-poems that culminates in questions), classical forms, Juhan Viiding*-like ditties, and, of course, wild thundering – a howl, of which Allen Ginsberg would approve. Among other styles, he even manages to tremendously pull off “entering”, which has been dismissed as a trend in Estonian poetry. In KMS’ variation, a single syllable or a couple of letters are placed on each line (only the king of the most underground of undergrounds in Estonian poetry – party animal and rogue Raul Velbaum – practices entering with greater severity; a single, sad character was printed on each page of his debut book).

Incidentally, KMS’ collection does not crumble to pieces, but vice-versa – its eclecticism and light distress form a logical and winding progression, and by following it, we find one of the best books written by KMS to date. Or, as he puts it (again, with almost untranslatable simplicity): “do / as / you / will // takes / where / you / need”.

The first poem in the work repeats itself meditatively, creating a hypnotic rhythm: “we’re a million we’ve a billion we’re a million we’ve a billion…” What that million might pull off with a billion like that is discussed throughout the rest of the book, all the way through a 16-page poem that drones at the back and a final, delicate prayer.

KMS’ poetry possesses a kind of warm humor, as well as a humbleness before his own talent for linguistic play as well as our odd, wonderful world: “my son / won’t be / conscripted // he’s no / astrophysicist, either // he’s read / too few books // he’s also / short on cash / (he’s got as much / as I give) // obviously / a hopeless case // you might tell me / he’s only six // but I’d want / everything / and right away”.

* Juhan Viiding (1948–1995), one of the most important Estonian poets of the late 20th century. See: “Six Estonian Poets: Juhan Viiding and others since him”, Estonian Literary Magazine, Spring 2016, pp 14–19.

Jürgen Rooste (1979) is a poet, journalist, and one of the most renowned Estonian writers of his generation. He has published fifteen poetry collections and received the Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Award for Poetry on two occasions, among many other literary awards.