Lilli Luuk appeared on the Estonian literary scene like a glimmering comet from a faraway galaxy – coming out of nowhere but taking her rightful place among the best authors in the métier.

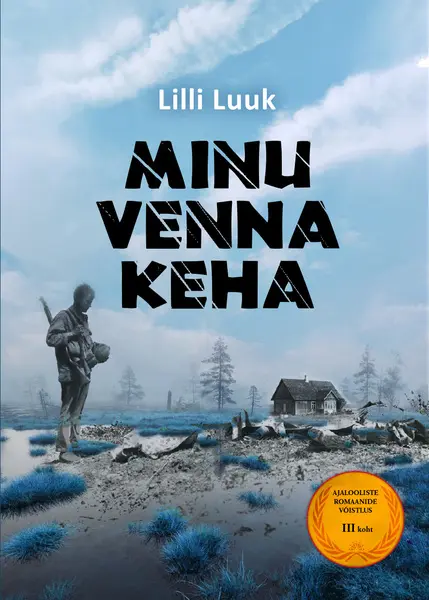

Luuk won the prestigious Tuglas Award with her very first published short story and nabbed the prize again three years later. In 2022, she made an impressive debut with two books: Miss Kolkhoz, which is composed of short stories that appeared in literary journals alongside several new texts, and My Brother’s Body, a novel that hit shelves even before the collection.

The author’s true existence was only verified once the books were released, albeit under a pen name. Just a few years earlier, even persons well versed in contemporary Estonian literature had their doubts, reckoning one well-known writer or another had decided to make a new beginning under a different name. Luuk has given interviews since the release of her books, but the mysteriousness remains tenacious. It turns out she is an art historian and former teacher who is now fully dedicated to writing and spending her weekends crawling through forests and trenches as a voluntary defense fighter, prepared to defend Estonia if such a day should come.

Luuk submitted the manuscript of My Brother’s Body, set during the Second World War, before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Had she waited a little longer, then the book might not have been published as is, as she discusses events that still lay at enough of a historical distance to be shaped into fiction. Events that should have been left behind the world for good. At least that’s what we all wished to believe. All illusions were shattered on February 24, 2022.

The story extends across several generations of Estonians whose lives were obliterated by the Second World War and the following occupation. A degree in history and a sharp eye for detail enable the author to bring long-ago events and circumstances into clear focus. Even more impressive is her ability to convey, highly magnified, the nightmarishly difficult psychological choices people face during times of upheaval. What use did the Soviet regime have for our brothers’ bodies – both the ones dumped carelessly into arbitrary graves and others that life abandoned at the moment of birth? Why couldn’t a woman have a grave at which to mourn her beloved, father, or brother? Why was it necessary to wipe out memory? Why was one forced to bear the weight of a fear so terrible that it was as good as impossible to ask even their own reflection what became of their father, brother, or beloved? How many generations are destined to seek the truth behind walls of silence?

These questions have regained relevancy and become much more acute in our everyday lives than we’d like to admit since war broke out anew in Europe. A person possesses nothing more precious than life. How can one live without feeling guilt for surviving? How can one tell which is the right side of history while still standing amidst the maelstrom and at a time when that which is obvious under later scrutiny might not be so apparent? My Brother’s Body inevitably reads differently now than it would have before Russia’s war in Ukraine. This isn’t to the novel’s detriment – quite the opposite.

Like Thomas Mann, Luuk could demand that her works be read twice over because only after the characters and plotlines are familiar can attention be channeled toward the books’ aesthetic qualities. My Brother’s Body is an exceptionally poetic novel and, despite the characters’ terrible trials, a delight to read. With poetic phrasing and details that are carefully picked to leave ample room for imagination, Luuk fosters sympathy that leaves anxious perspiration trickling down the reader’s back, the smell of death invading their nostrils, and a silence that haunts the awful events and cuts deep into flesh and bone. Only after the journey is complete does the reader fully understand the opening sentence: “Their future is seized by force, shredded right in front of them, their opportunities, newly budding potential, abilities, desires are cast aside, it all rots before their eyes, rapidly disintegrating at an already unattainable distance over days, over months, the talents granted at birth left neglected and less vital as years go by, their joy losing validity.” It is precisely what criminal regimes’ wars and occupations inflict upon the lives and fates of entire generations.

Luuk’s short stories are also layered and intricately woven: one must repeatedly reopen the pages to understand everything embedded within them. With particular poignancy, she depicts the Soviet occupation and the transitionary period when Estonia regained its independence. Yet, states are not born in an instant and the human psyche cannot transform in a day. Quotidian conditions are extremely slow to follow tremendous changes, and it takes generations to shed the mental symptoms of living under a dictatorship. There exist terrible events, the memories of which will never extinguish and will continue to plague the victims’ relatives and offspring who have no personal experience with war or occupation.

Some of Luuk’s stories, such as “Miss Kolkhoz” itself, can be read as a belletristic lesson on Estonian history. The first and plainest layer is a horrifying account of domestic violence: a girl whose mother beats her so badly that she sometimes must skip school and lie in bed to recover runs away – but where and with whom? Telling clues are given, faithful to the era in question. Why shouldn’t a rural farmgirl want to win a beauty pageant? It’s nothing out of the realm of possibility, is it? They showed how wonderful that life is for five straight hours on TV! Why not send in nudes when asked? It’s obvious that the bikini round is the most important part of the pageant.

Readers familiar with Estonian history can easily place the constellation of recognizable details in time: 1988. The Singing Revolution had already begun, and the restoration of independence would come just three years later. The first beauty pageants since the Second World War were held, Estonian track cyclist Erika Salumäe won an Olympic gold medal, and the Estonian Sovereignty Declaration was issued. One can only admire the psychological agility with which the author takes the reader by the hand and envelops them in a thrilling web. Excitement and captivating psychological tension are also the primary forces that keep one from putting down either book until the very last page.

Lilli Luuk entered the Estonian literary scene to stay. She is brimming with creative plans and there’s no doubt her next work will be an immediate hit.

Lilli Luuk

My Brother’s Body

Minu venna keha

Hea Lugu, 2022, 183 pp.

ISBN 9789916702246

Miss Kolkhoz

Kolhoosi miss

Saadjärve Kunstikeskus, 2022, 167 pp.

ISBN 9789916414699