Elusamus 2019, 72 pp.

ISBN 9789949735013

The role of nature in poetry has, foremost, traditionally been ornamental, atmospheric, or metaphorical. Lately, however – in the winds of climate crisis – the environment has adopted an unshakable position in societal discussion and has thus acquired a different appearance in artistic representations as well. Environmental issues are no longer a secondary reality towards which one can – if they have the time and desire – turn their attention. On the contrary: it’s becoming impossible to refuse to recognize them. As a result, “apocalyptic exhaustion” has become an item of discussion. The incessant flow of information proclaiming imminent catastrophe has caused people to feel passive and unsure of what, if anything, they can do about it.

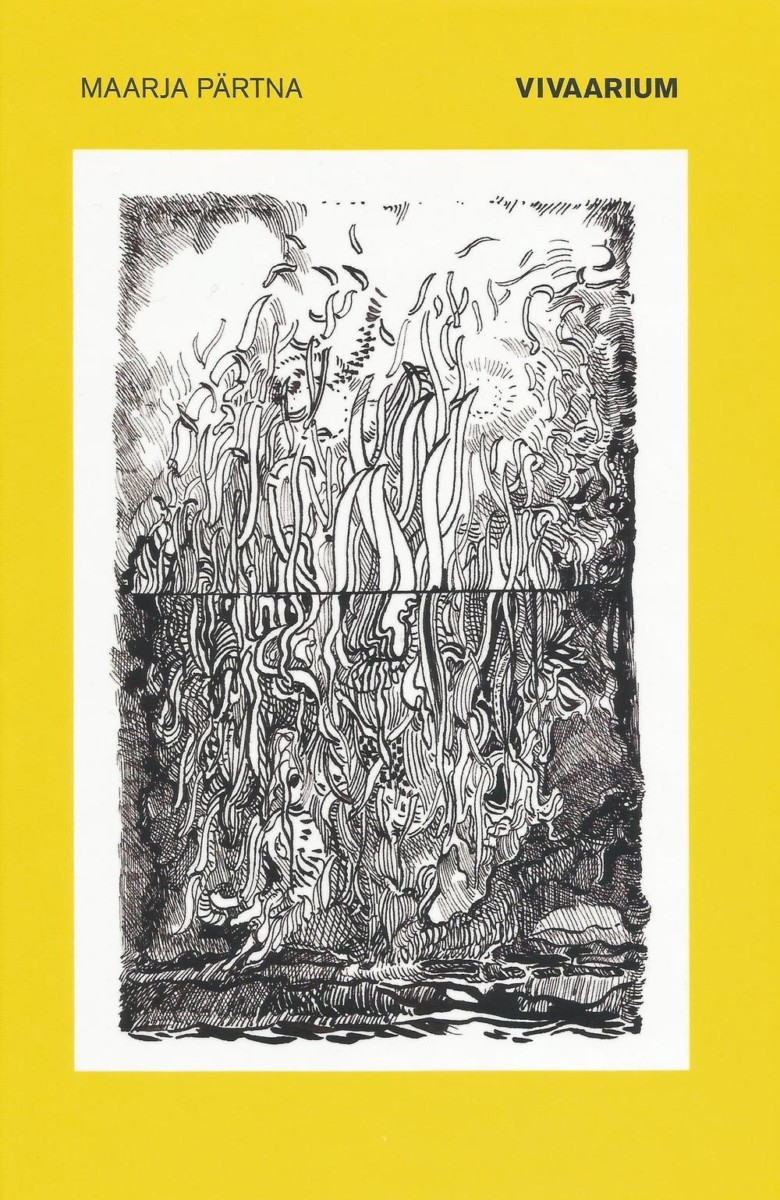

Maarja Pärtna’s fourth poetry collection Vivarium deals with this sense of numbness. She attempts to utilize the language of poetry to locate our lost sensitivity. Although Vivarium’s environmentally-themed aims are explicit they, luckily, don’t evolve into an “agenda” that makes the poems too predictable. On the contrary: Pärtna’s talent lies in her sensitivity for detail and for conjuring unusual imagery, the metaphorical function of which is not immediately apparent. Thanks to this hint of mystery, comparisons become especially powerful. Take for example “a lilac branch in a vase – or its shadow / like a memory left bodiless” (p. 23), or her acknowledgement that history is a storytelling of graves “that are likewise akin to walls / meant to hold the dead / right where they belong.” (p. 30)

The more shadowed side of sensitivity is a vulnerability that characterizes the emotional tone throughout Vivarium. Humans no longer stand at the center point of power and usual self-centrism is disrupted on several levels. People are not always the narrating subject in Pärtna’s poems, for instance: first-person experiences may also be described by a dead kingfisher (pp. 46–47) or a gutted animal hanging from a hook (p. 49). The author repeatedly notes how human attempts to act independently of nature have failed time and again, such as in the form of man-made structures that nature overtakes and overgrows without asking our permission (pp. 18–19, 22–23, 28). One is forced to admit: even that which is regarded as an intrinsic element of culture (such as the art of formulating words) is guided by something other than self-governing human will: “and gradually I begin to perceive / it is impossible to direct / the path of words through the world.” (p. 16) It’s also worth noting the recurrence of certain imagery and lines throughout the poems, evoking the sense that there is no topic that can be easily “framed” or resolved by a single poem. Rather, these subjects require greater scrutiny, responses, and responsibility.

The narrator’s voice in Vivarium is that of someone who has been startled into a state of caution – a person who, having become conscious of the shift in the relationship between man and the forces of nature (as well as the impossibility of contrasting the two), is seeking a new manner of relating to the world. What matters most is to not grow numb or disengage.