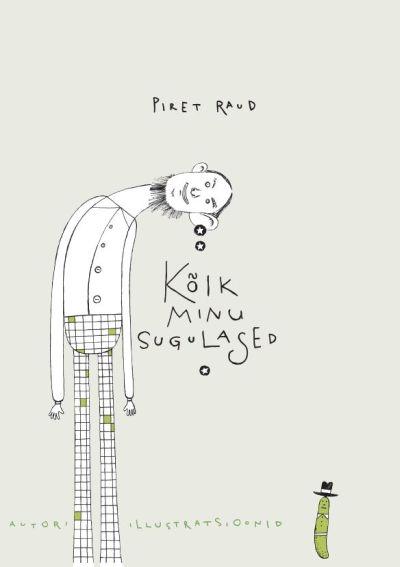

Illustrated by the author

Tänapäev 2017, 116pp.

ISBN 9789949852314

The narrator of Raud’s All My Relatives, a boy named Adam, is far from being the first and only representative of mankind or of his own kinsfolk. Quite the opposite: when Adam’s teacher instructs the students to draw their family trees, the boy finds he can list off so many relatives they just won’t all fit on one. So, he draws a centipede instead. Each leg is unique and goes at its own pace, different in terms of how far it can step, but all still moving in one direction determined by the spirit of their common heritage.

Here, we find the book’s first grain of knowledge worth pocketing. A child knows their kin. Stories have been told, heritage passed down from generation to generation, and family members communicate. Family can be known and recognized even without seeing one another or shaking hands. How many kids can boast that they know all their “kith and kin”? Another useful tidbit is the fact that all people are unique – even relatives. Some are nice, some are funny, while others may be strange, beastly, or vile. It’s not out of the question for there to even be an ex-con in their midst. Some of Adam’s relatives are new to the family (his little brother, for one), while others are so old that to keep things clear and organized, he draws a sword clutched between the toes of their centipede leg.

Raud views family ties through a child’s gaze and talks about them in just as childlike of a tone. Youngsters are often told they have the exact same nose as their father (grandfather, great-uncle, etc.). Or their eyes. Or their jaw. How does this work in reality? Is Great-Grandpa Eduard, who passed his nose down to Adam, now lying noseless in his coffin? People also say that dogs resemble their masters. What if it’s the other way around? And what happens when pet and master blur together to such an extent? Absurd tales like these provide food for thought after you finish laughing.

Readers who immediately make up their mind that the book is a realistic and childlike work that details the affairs of a particular family and kin are in for a surprise. All My Relatives holds an underlying connection to Raud’s 2014 book of children’s stories titled Me, Mum, and Our Friends of All Sorts, in which a little boy named David recounts the rather bizarre encounters had by the people around him. By writing about the extraordinary as if it were ordinary, the author crafts well-functioning imagery that, despite its slight quirk, is as on-target as Robin Hood’s arrows. For example, while visiting his Great-Aunt Aime, Adam meets an uncle who is a bona-fide pig and behaves that way as well – the man is filthy and domineering. The uncle won’t leave until Great-Aunt Aime dumps all the coins in her purse into the slot on his back. No surprise there – these days, there’s no shortage of relatively young, unemployed men who happen to come along right when their older relatives receive their pension payments.

No matter how wild and mischievous every subsequent story might appear, it always arrives at a clear message that Adam or an adult uses to sum up the situation. Following the incident with the pig-like uncle, Dad remarks that you don’t pick your relatives. All you can do is try to remain human yourself. Discussing their bland Aunt Blaine who melted into a couch, Dad remarks that modesty is certainly a virtue, but you still have to stand up for yourself – otherwise, people will do whatever they wish with you.

Raud wouldn’t be a writer if she didn’t also appreciate reading – something she conveys in several stories. Adam’s sister Mia is drowning in stuffed animals because they bring her wonderful dreams. The Moon recommends instead that Mia read: “You can take a book to bed with you, too. Books also make you brave, and you’ll definitely have lovely dreams after a nice little read. Most important of all: you can never have too many good books.” Instead of balancing books on her head to acquire a ladylike posture like one relative did, one character decides to read them. “Grandma once said, by the way, that Aunt Angel had gotten it all wrong. True ladies aren’t those who can walk with a book balanced on her head, but those who read the books and are friendly and kind to boot.”

Fun is also poked at goal-oriented sports on several occasions: a talented football player loses his hard head, but there’s nothing wrong with that – he’s still got his legs! A girl who goes on a healthy carrot diet to be better at sports turns into a bunny, then a chocolate bunny, then a mug of hot cocoa, and finally a girl again. “It’s unlikely that Lena will become an Olympic champion anymore, but after all, the Olympics aren’t what matters most in the world.” What truly matters is family and being loved just the way you are.