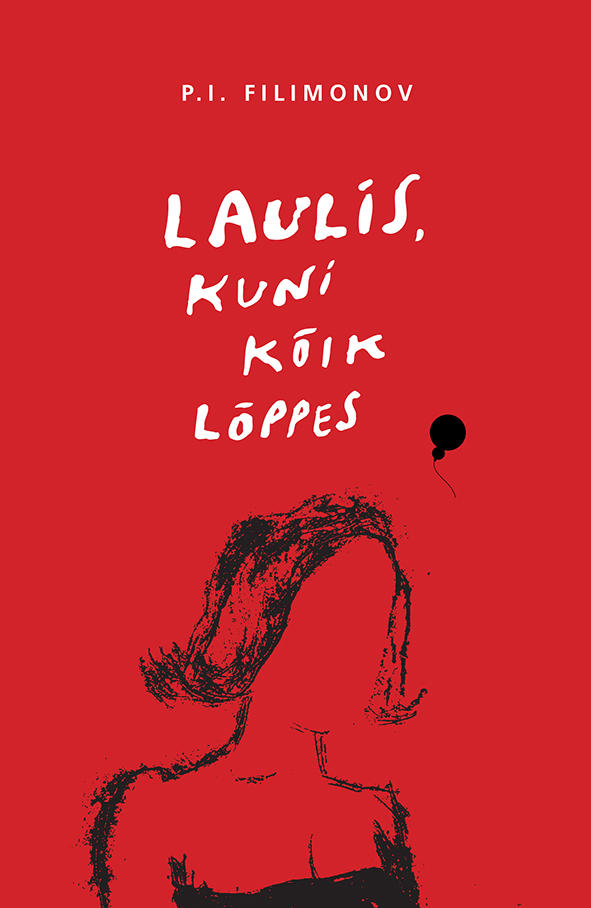

P. I. Filimonov, Laulis, kuni kõik lõppes (She Sang to the End)

Tallinn, Varrak, 2016. 312 pp

Translated into Estonian from the Russian by Ingrid Velbaum-Staub

ISBN: 9789985334539

For ethnic Russians living in Russia, Russian-Estonian culture isn’t even a proper diaspora. If only it were across the Big Pond – but right here, in their former colony?! And they’re writing things?! It’s possible that is how Russian-Estonians see it, too. Proper Russian literature is written over in Russia, but here in Estonia… I should ask P. I. Filimonov (1975) himself, but perhaps assuming that his books currently reach Estonian-language readers more than they do Russian-language readers is justified. So, what on Earth is the cultural space, in which he lives and breathes?

In any case, P. I. Filimonov is living and breathing just fine, since his novels and poems are widely published in both Russian and in Estonian. Furthermore, he is a remarkable performer – a true performance-poet with his own signature voice and manner, and occasionally even takes the stage with a band. In some sense, as a result of his sarcastic sideways glance or being on his own level, Filimonov makes the process of categorizing his new book Laulis, kuni kõik lõppes simple, even though the text itself seemingly resists any kind of categorization at all. Simply put, it is a sort of post-modern novel, in which misleading or guiding allegories constantly jostle us and the protagonist away from the main plot. It is a science-fiction story that simultaneously addresses lethargy, intellectual anxiety, and literary being.

The protagonist is 27-year-old Olympius – a young Russian-Estonian whose relatives charge him with caring for his dying grandmother. Not that he is against the task, of course – the work is certainly demanding, but it has its own bonuses, such as material ease, a certain opportunity to not have to jostle and face the daily grind in competition-based society, a sense of enjoyment from knowing that he is being somehow altruistic, etc. Yet, things aren’t so simple. Namely, his grandmother draws him into her surrealistic stories, truly sucking our protagonist into bizarre narratives (if she is even telling them at all – or rather showing him magically?), at the end of which Olympius’ own presence or role in the allegory is always revealed. Or, alternatively, his role in a spirited game of track-covering (do they help the reader catch whiff of the novel’s secrets, or purposefully make everything more playful and complicated?). The character’s grandmother simply grabs him by the hand, and he’s instantly gripped tight by the storytelling. All of the tales are a little strange; even brutal. Olympius is a character in varying eras; in different psychological roles; in alternating nightmares and perversions. In the end, he always finds out who he was in the given story (such as a narrator, who is pathologically in love with his twin brother).

On top of all this, it is soon revealed that the building in which Olympius’ grandmother – who is trapped in the spirit of the communist era – lives (or, to be more precise, dies over the course of the book) is starting to slip into a hole in time together with the nearby blocks; to detach from the world familiar to us. Thus, the characters are in danger of becoming caught in a gap in time.

On the one hand, the novel can be read as an existential literary joke – at some point, it seems like Sartre-like disassociation has been brought to a pinnacle. The main character certainly cares for his grandmother mechanically and by motor memory, but his soul is callous. He is indifferent about everything, which is conveyed through a certain lackadaisical prism – horror forces him; it’s easier this way… But this doesn’t last to the end, either. In addition to a sense of responsibility, a special kind of care germinates within him (if it hasn’t been there all along). It is as if he breaks the law he himself has repeatedly confirmed: that we, as humans, are all lackadaisical clods. As such, Filimonov’s book can also be read as an entirely sincere contemplation of existential problems, morals, extreme situations, and isolation; so what that the author provokes us all too often with dark humor and the protagonist’s worldview – one that extends to nihilism, but is timid.

Humor – a cocktail of deep intellectualism and entirely out-of-place crude comedy – is Filimonov’s tool. So, despite its tortuous agitation, dark events, and nightmarish atmosphere, Laulis, kuni kõik lõppes is also a very funny book.

The work can be read as an existential discussion just as it can be science fiction (not that one ever inherently negates the other) – all the good requirements for a work of fantasy have been established. And not only established, but accomplished, too. Although we may interpret the entire story as a bout of madness suffered by the protagonist, signs point more to some kind of Scythe of Time or Steven King-like idea. It is a place with frozen air and energy, “as if time stood still”, and which indeed turns out to be their tumbling off the brink of time; away from our everyday lives… There is also a very significant and unreal note to the book’s maggot plot-line. Specifically, it’s revealed that maggot-aliens nest in our brains if given the slightest chance – one part of their grand plan for world domination. Among other tidbits, it turns out that a maggot lives in Putin’s brain, also. There is dimension and breadth to the work; no matter that most of its scenes seem to unfold in a stuffy Stalinist apartment, which has furthermore been left out of the stream of time.

Another important part of Filimonov’s writing is the way, in which he handles a special aspect of masculinity; an image of manliness. This surfaces repeatedly in both the central plot and in several side-stories – constant emphasis is given to how and in what way characters are a certain type of “real” man. He observes how they think. How they view women. How they interact, become fathers, and buddy up.

Filimonov’s network of references, well-read background, familiarity with history, and ability to approach the “wisdom” scattered throughout it with (self-)irony make the novel quite unique. Still, I would advise translators to keep the Russian-language original at hand or to work from it, since the Estonian-language version displays signs of rushed work and possesses influences from Russian-language structure and word order.

In some sense, Laulis, kuni kõik lõppes is an irritating, grating, William Burroughs-like work of absurd fantasy; on the other hand, it is a mellow narrative – a light jab on the topics of status-quo literature, which asks what we are doing here in the first place and how it all appears outwardly; how pitiful we can be. It’s a shameless book – what’s there to say?

Jürgen Rooste (1979) is a poet, journalist, and one of the most renowned Estonian writers of his generation. He has published fifteen poetry collections and received the Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Award for Poetry on two occasions, among many other literary awards.