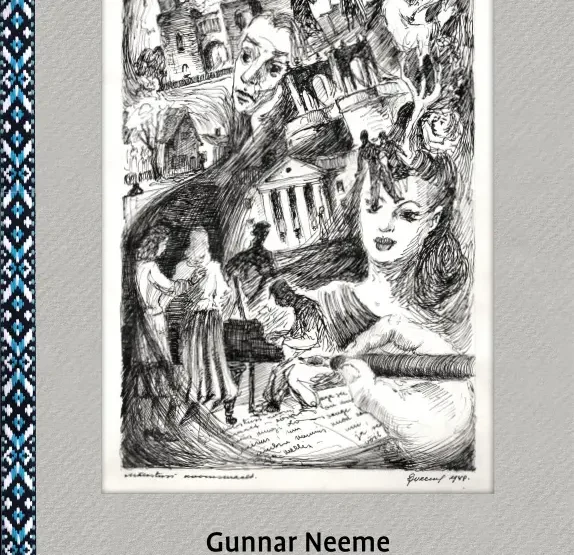

Heiti Talvik. Legendaarne (Legendary)

Tartu: Ilmamaa, 2004. 303 pp

The title of this book, drawing together the small number of works – poetry, essays, literary criticism and a selection of more important letters – that the Estonian poetry classic Heiti Talvik managed to write, is quite striking. During his lifetime, Talvik published only two well-structured collections of poetry: Fever (Palavik) (1934) and The Day of Judgement (Kohtupäev) (1937). Talvik, who considered himself a disciple of Charles Baudelaire and François Villon, as well as Russian poet Aleksander Blok, and thus belonged to the decadent tradition of “damned poets”, also tirelessly manifested the ideas of freedom and democracy in his works. He was acclaimed by critics and his poems have been lavishly quoted ever since they were published. Due to his uncompromising defiance of his tragic fate and devotion to spiritual values, even his life became a legend. Talvik was born in 1904; he studied at the Faculty of Philosophy of Tartu University, but, restlessly striving for perfection, did not graduate. At the end of the 1930s, he became one of the most prominent members of the poets’ group Arbujad (Soothsayers), and he married another poet of the group, Betti Alver. Talvik was arrested in 1945, and since he declared that he could by no means be loyal to the Soviet regime, he was sentenced to five years in a Siberian prison camp. He died in Tjumen district, Russia, in 1947 and his grave remains unknown. The unity of Talvik’s works and his biography created a mythical narrative of an unbreakable and uncompromising martyr-like priest of the spiritual life. In addition to Talvik’s own texts, the collection Legendary contains an important part of the reception of his work – critical analyses and evaluations – comprising about a third of the contents of the book.

Talvik, whose poetry developed under the influence of French Decadence, Russian Symbolism and German Expressionism, strove for classical precision and formal strictness; he expressed his ideal in the lines “We were born for stanzas, slim-built and firm/ to imprison the fury of Chaos.” The idyllic romanticism of his first poems grew into a sharp social and even prophetic cognition of time, reflected in his poetry by elaborate aesthetic means. The influence of Pushkin and Dante, admitted by the poet himself, can more strongly be felt in his later poetry. Defiance and desperation, protest against the mercantile world, neurosis and inner tensions, nightmarish visions and the ecstasy of death, and the disease-causing agents growing in pre-WWII society are all overcome by transforming them into art. Talvik’s poetry expresses, in a unique way, his own intense spiritual quests and offers a poetical analysis of the historical situation of the time. Talvik’s attitude towards life is individualistic, and his altruism is quite similar to the Christian Gospel, but he is cuttingly critical of any authority.

Just like his poetry, Talvik’s essays and articles quite early drew attention to the dangers of dictatorship and war in Europe. At the same time, all of his work is timeless, not confined to the limits of a certain period; it is worth reading as an aesthetic manifestation of ethical values and personal freedom to emphasise the role of beauty and poetry in making the world a better place.

Lauri Pilter. Lohejas pilv. Romaan lühijuttudes. (A Dragonish Cloud. A Novel in Short Stories)

Tallinn, Tuum, 2004. 204 pp

Lauri Pilter (b. 1971), who earlier published some translations from English, earned his first critical recognition – the Friedebert Tuglas Short Story Award – just before the publication of his debut book. This award testifies to the author’s masterful skill, polished language and sense of form. These attributes can be found in his new development novel, presented in eleven short stories and characterised by critics as a portrait of the artist as a young man, obviously referring to James Joyce.

Pilter’s work really is greatly based on secondary inspiration, revealing, besides the already mentioned Irish exile, his love for Marcel Proust and, mainly, William Faulkner. The title of the book refers to the line “Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish” in Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra. But actually, his highly cultured hints, also including Beethoven’s music, serve the creation of a spiritual milieu and tension. The eleven short stories of the book are joined into a whole by the protagonist Lavran, who studies English philology at the university. After having received an inheritance from his great grandmother, he studies some more in Boston, and after that works as a teacher in a small holiday resort, which is also his childhood home town. Some episodes of the book are set in Latvia and also in a psychiatric hospital; the story of the young man also briefly but clearly outlines his descent.

Pilter’s protagonist seems to be goaded by an identity crisis: his wish to write fiction stems from Faulkner, but the situation in Eastern Europe does not allow the development of characters that would be an example of extreme individualism, ruining themselves through their own arrogance. Throughout recent history, too much has depended on Russian communism, German national socialism or corporative nationalism here in Estonia; all dramas and tragedies in the neighbourhood contain the deportations of families to Siberia, shootings on the banks of ditches or in cellars, deaths in wars or the fighting of fathers and sons or brothers in opposing armies, all resulting from the work of external powers. This gives rise to his own passion for self-establishment, and in his youthful maximalist attitude, he requires of a small nation things that would have been fitting for a large nation. His psychological and religious quest, a self-search wavering between desperation and mental disease, and his belief that the acquisition of several identities makes a person strong, inspired him to accept the Russian Orthodox faith in order to experience a feeling of participation. And after that, a development which is actually the red line crossing through the whole book, he attempts to become Jewish.

We might suppose that his following of his obsession would be comical, even tragicomical and pathetic, but it is not. A sad feeling of loneliness casts shadows on the quest of the protagonist, who is quite close to the author. The quest, in spite of its spatial dimensions and events that occur during it, is in fact a spiritual one. He is fascinated by Jewish customs and traditions, which are described in detail. He visits synagogues, tries to behave as a Jew, even undergoes circumcision, and falls in love with different Jewish women, but still he is driven away from everywhere as a stranger. And that’s what he is. He reads the works of his favourite philosopher, obviously, Spinoza, the only Jewish philosopher in Europe who differs from orthodoxy by his divination of creativity and the created things. The last story of the book, “Spinoza and Attributes”, is very clearly the author’s personal credo, in which he analyses his personal perceptions of love, kindness, understanding, beauty, strength, eternity and creativity. The story also expresses gratitude to his creators – his parents, and maybe God. A bitter drop in these words of thanks is his regret over the lack of mysterious and fulfilling love of a woman of his own age.

Pilter’s book is about the fate of a spiritual and searching man, who is lonely in his romantic fascination with pre-Civil War America and in his admiration for all Jewish things. At the same time, this book is about the need for human warmth and participation in our world. The eternal loneliness that seems to be the heritage of the protagonist embodies vast sadness, but also, brightness that cleanses the spirit.

Rein Raud. Hector ja Bernard (Hector and Bernard)

Tallinn, Tuum, 2004. 232 pp

Rein Raud (1961), writer, translator and Professor of Japanese language and literature at the University of Helsinki, has published works in all genres of literature. His recent critical comments in the newspapers on political and social subjects have steered his literary work toward the prose of ideas as well; Hector and Bernard, balancing between genres, is a good example of that.

The author who explained the background of his work in an interview given after the presentation of the book, admitted that at the beginning of the work he had kept Plato’s dialogues in mind as his models, but during the process of writing, the book got closer and closer to Voltaire’s Candide. Mostly, the book presents the talks of a scholar Bernard, who has withdrawn from public life, and a younger poet and translator Hector at the dinner table, and with a glass of wine in front of a comfortably blazing fire. The first conclusion the reader draws could be: an armchair philosophy, the amateurs. Such conclusion could even be confirmed by a fact that after having arranged the material side of his life, Bernard, living alone, has not left his flat for ten years. Having been a well-known intellectual figure, he had attended conferences and belonged to exclusive clubs in his younger years. Now, he sees such activities only as the degradation of the dialogue, and he is very sceptical about people’s ability to make the world that is based on market economy a better place. His relations with the poet, who suffers from a writer’s block and seeks new inspiration and the ‘touch of the real’ in women, are warm and trustful. When Hector spends some time in Paris with the translator’s stipend, his letters to Bernard describe his participation in an aristocratic Frenchwoman Chantal’s well-organised life and talk about her rhododendron-scented bath foam; he tells Bernard about the primeval and unrestrained rhythms of an African woman Mbebe; he describes the desire of a Rumanian painter Cornelia to have an absolutely modern life; he talks about his platonic relationship with Celeste who studies existentialism; he also writes about his passionate nights with an American woman, a late hippie, who had included an affair with an European man in her travel plans. These letters form a mild caricature that complements the philosophical fireside talks about the modern alienated culture of the Western world between the two men who are drifting spiritually close to each other.

The laconic but intriguing plot of the book is mostly about the events that occur outside Bernard’s residence, about the relationships with women of both men, and it is topped with a witty and unusually happy (for modern literature) point. Raud’s book is a philosophical and essayistic novel of deep content and comfortable form, enjoyable to read, and offering much material for reflection.

Aarne Ruben. Elajas trepi eelastmel (A Beast on the Landing)

Tallinn, Tuum, 2004. 237 pp

Aarne Ruben’s (b. 1971) first novel Volta Whistles Mournfully (Volta annab kaeblikku vilet) received First Prize at the novel competition in 2000. The book was inspired by the social democracy of the early 20th century and by the Dadaist movement in Europe, and revealed the author’s interest in history and his capacity for thorough research. Ruben’s second novel A Beast on the Landing, which is set in the 15th century, affirms the deepness and continuity of this interest.

The plot of the book is framed by the execution of Jan Hus at the stake in 1415 and the battle between the English and French at Agincourt in the same year, but the latter event is given in the form of a military historical retrospect in the penultimate chapter of the novel. The laconic plot embodies the reflection of a Livonian nobleman on his own life, containing happy memories from his youth and his first romantic love affair, his studies at the University of Prague, travels with the Irish monk Collatinus, marriage to Kuningunde, a young daughter of a rich Lübeck merchant, and finally, his travelling to Paris and obtaining a professorship at the University of Paris. This rather eventless main plot line is enlivened with other stories from good old Livonia, theological and juridical disputations and plentiful descriptions of the customs and circumstances of the time. Now and then the narrator directly addresses his readers, for example, when talking about his marriage: “The reader has already many times looked into our life; this is the most ordinary marriage – just a man and a woman.”

Ruben did not aim to write a traditional historical novel that would find analogies in modern times or would be full of dynamic adventures. His fiction is set against a believable background of real events, some historical persons who do not have any contacts with the main hero of the novel, and a specific geographical location. Each sentence is suggestive of history; the book resembles a work written by a historian who has made good use of literary narrative.

We see the protagonist as a skilful bluffer who, although penniless, can parade his chivalrous virtues and climb the career ladder. But when considering the meaning of the title, we can see here a suggestion of the birth of a Christian in the backlands of Europe: a beast can only see the landing of the stairs that symbolises the newly Christianised lands. The explanation is not easy to find. Ruben has written quite an unusual novel, or, maybe this is simply a story about Time.

fs, 2004

Tallinn, Tuum, 2004. 79 pp

The author (b. 1971), who published his first poetry collections under the French-sounding penname François Serpent, has kept only his initials in his third book, and the title of the book is just as laconic. The epigraph of the book was chosen from George Orwell’s novel 1984, directly indicating the fact that fs has studied his surrounding milieu in real time, projecting other layers over it.

The free verse poetry of fs lacks punctuation and does not aspire to create special images, but its verses fire away in short unmerciful and accurate bursts. His world is a bleak urban environment, dominated by black and white like a film noir, where only street dust and some hints of blood bring some shades of colour. This direct poetry avoids metaphors and is largely based on autologous use of language; it finds its material in life in its naturalistic and even brutal forms. “this thing is life/ it is no poetry/ here are no metaphors”, says the poet himself.

Among younger Estonian poets, fs is the most stylish existentialist who, groping in darkness and discovering the world, suddenly finds himself existing in an extreme situation. The line “death is transported by trucks” is repeated like a chorus in several poems; “the cold loneliness of a razor edge craves for blood”; two-sided passion and two-sided sadness means double loneliness. The generally quite hopeless mood of the book is softened only by some self-ironic details: the poet, who pulls on his leather pants in a hotel room, sees his reflection in a mirror as an existentialist joke, slightly reminding him of Iggy Pop.

The poetry of fs is sincere, stern and virile; its language is simple and easy to remember; “f is like f, s is like s, a man is like a man.” But how can we relate the world depicted by fs to Orwell’s dystopia? The epigraph of the book is about torment and the greatest humiliation – the loss of identity – brought about by betrayal by the closest person. But from the stern and bleak reality that fs creates with the help of visually cutting associations, the need for faithfulness and love emerges, and one rhetorically asked essential question, “can i keep her/ whom i love”.

Dagmar Normet. …… ainult võti taskus (Only a Key in My Pocket)

Tallinn, Varrak, 2004. 328 pp

Memoirs and life stories comprise a growing part of the Estonian original book production of recent years. Their success depends on the life and the past of the author, but naturally, even more on the author’s writing skills and his or her original points of view. Very many Estonian literary and cultural figures have also published their memoirs. Dagmar Normet (1921), a successful children’s author, published a well-received book of memoirs The Opening Doors (Avanevad uksed) in 2001, recently followed by …Only a Key in My Pocket.

In her previous book the author discussed the years of her childhood and development in pre-WWII Estonia. …Only a Key in My Pocket does not require the knowledge of the previous book — it is an entirely independent book, colourfully describing the author’s experiences during the war years. Normet writes with great emotion about her everyday life behind the Soviet lines during WWII.

When the war broke out, the Soviet occupational government evacuated the members of the local communist puppet government, as well as the families of Soviet activists and sent them back to the Soviet Union. Jewish families were also offered the opportunity to leave Estonia. This is how Dagmar Rubinstein (her Estonianised family name was Randa) left Estonia as a student. She had, after having graduated from a gymnasium in Tallinn, entered the University of Tartu to study physical education. Her book begins with a description of a long train trip and reminiscences of those who were left behind, followed by pictures of Russian towns as seen by a young Estonian lady of a good family: masses of people, dirt and dust, slogans and posters, all typical of Soviet reality. Her winters during the war were spent in the overcrowded city of Uljanovsk (Simbirsk), at first working and later studying. Besides the unaccustomed conditions and difficulties of the war, the book is mainly about the young people of these years, not given as a story of a lost generation, but as one of certainly unusual maturing. In the autumn of 1943, Dagmar Normet was able to go to study at the Moscow Institute of Physical Education. The book closes with her return to her homeland, with a young love and a new beginning. Reminiscences alternate with selections of diary entries from that time.

Naturally, numerous volumes have been written about those years on the front as well as behind the lines. But in the Estonian context, Normet’s book is distinguished from all these by the fact that since the regaining of independence, very little has been said about the evacuees to the Soviet rear. Also, all memoirs and works of fiction published in the Soviet time were subjected to censorship, which excluded certain subjects and allowed only one segment of reality to be exposed. The most representative Estonian novel about life behind the lines, Lilli Promet’s A Village without Men (Meesteta küla), was somehow able to evade censorship; Normet’s book offers a valuable addition to this earlier work. The book is a self-centred story of a young person’s discovery of the world, touching upon the recurrent and universal subjects for young people of those years – I am here, where are you?; a letter from far away; great losses and some unexpected joyful discoveries; and finally, a lost and destroyed home, only the key of which has been left in the pocket.

Asko Künnap. Ja sisalikud vastasid (kolmes kirjas). (And the Lizards Replied (in Three Letters))

Tallinn, Näo Kirik, 2003. 67 pp

The publishing of Asko Künnap’s (b. 1971) collection of poetry created more excitement and caused more fuss in the press than many other and not worse books of poetry. This is the debut book of the author, who is a designer by profession and who has so far only appeared together with others in collections or small presses. Künnap’s book was given the Estonian Cultural Endowment Poetry Award in 2003 and was, thus, acknowledged as one of the best poetry collections of the year along with Toomas Liiv’s volume of selected poems, which received the major poetry award of the Cultural Endowment (See Elm 2003 Autumn: Toomas Liiv, Poems 1968-2002).

And the Lizards Replied is an almost perfect book of pure style, since the content and the design, the text, the script and photos form a unity and amplify each other’s effect. The book contains 40 texts in three cycles. Some poems have English translations, one has a Russian translation, and some of them are accompanied by stories that tell about their birth or give some self-ironic commentaries. Playfulness and seriousness change places subtly, and the result is stylish, faultless and cultured. Künnap varies his moods, sometimes playfully, sometimes with a nostalgic desire for unpretentious and real existence. His world is a modern world, striving for internationality and for the beauty of the game; he self-consciously brings together well-maintained mannerism and well-maintained simplicity – the result offers enjoyable reading, but as a rule, it does not scratch, irritate or jolt, as does the poetry of some outstanding shocker or some hardened world reformer.

My vain pictures –

line flirting into pure gold,

All converging, not a single parallel.

can’t believe, can’t believe the fairness of the verdict

on these pictures of mine!

the rain will rise over Europe, pulsing with pain

and the continent will applaud.

Applause.

(p 30)

Toomas Kall. Armas aeg (Dear me)

Tallinn, Tänapäev, 2004. 328 pp

Toomas Kall (1947) is a playwright and a script-writer; he is one of the few good writers of variety scripts in Estonia. In a word, he is a humorist, whose plays have enjoyed huge stage success. His jokes, which the public has been able to enjoy already for twenty five years, have been especially topical during difficult times. His political jokes, and chiefly, a TV series parodying modern Estonian politicians, have recently found the warmest reception, but also caused polemics, whether he’s gone too far now and then.

Kall’s characteristic methods are literary parody and the almost absurd-reaching travesty of his texts, where he ruled the floor up to the arrival of Andrus Kivirähk in the literary scene. If we compare these two favourites of the variety-going public, we could say that Kall’s jokes contain more intellectual tension, and their essence is more hidden, abstract, and drier than Kivirähk’s crazy hyperboles and grotesques.

Dear Me collects Kall’s texts of recent years that have mostly been published in the press, also containing interviews, anniversary articles, essays, commentaries, drama sketches and diary entries. But – all these can be defined as parodies, with an exception of anniversary articles. His interviews are held with imaginary persons, but refer to real interviews with certain real persons. The anniversary pieces are written to mark real birthdays of real artistic figures, but even these are funny. Naturally, the majority of Kall’s texts offer the joy of recognition to the public who is familiar with Estonian life, but not only: many things that have gone astray in Estonia may go astray everywhere. Kall makes his readers laugh at sheer self-confident stupidity and at exuberant self-promotion, at the elections and the elected, at all kinds of historical events and historians, at the stars and losers, at the gender problems, etc. Everything has already happened and will happen again some time in the future. His pieces, presented as letters, columns or commentaries touch upon and reflect almost all spheres of Estonian life.

The book ends with Uku-Ralf Tobi’s diary from the year of 2002, given as a diary of a person who frequents artistic circles; it resembles a reportage of the year’s cultural life, or, it is a slightly distorted chronicle of time, given through an enjoyably askance look, containing inside jests and jokes of the community and (self-)ironical reflections. The mirror of the diary does not reflect only time, but also the narrator himself, and the image gives the joy of discovery and recognition. Some examples to confirm it:

9 June. Sunday in the country. The sun mows the lawn. The ground is thirsty. Going back to town, I felt the same that I have repeatedly felt already earlier: if you have not spoken to anybody during the day, an oppressive feeling of guilt develops by the evening. And I do know why it is so – he who is silent does not talk about holocaust as well.

18 June. The Parliament gave the impression of denouncing the communists, telling them something like, “You were bad, but you should know that we know about it”. The practical meaning of this denouncement is not clear – I do not know what it will give to me personally. To start with, I feel like a hunter who has been given the permission to shoot a mammoth.

Ervin Õunapuu. Eesti gootika II (Estonian Gothic II)

Tallinn, Umara, 2004. 190 pp

After his powerful arrival into Estonian literary scene in 1996, Ervin Õunapuu (1956) has published already eight books (see Elm 8, 10, 12 and 15). His latest work, Estonian Gothic II, is an imaginary sequel to his Estonian Gothic I, published in 1999. Õunapuu, an artist with a strong and prolific creative nature, is well known as a painter and stage designer, script writer and producer, but lately he has stated that primarily he wants to write. He is a surpassingly spontaneous narrator, a powerful visionary and a passionate fighter, but his prose is, foremost, meant to feed the appetite of spiritual gourmets, not to be gobbled down as fast food. The stories he tells are never ‘nice’, rather, his passion is to break up all kinds of idylls, to discover veiled horrors, to look behind the picture, to open hidden boils and reveal infected places. Õunapuu can very often be characterised as a surrealist of unsurpassable fantasy, who now and then lapses into amazingly detailed realism.

Having first tried to learn about the individual’s position in the Universe and sought to catch the uncatchable, in several next books Õunapuu launched his own one-man atheist resistance battle against religious blindness. Now, Estonian Gothic attempts to solve the collective myths of Estonian history.

The second selection of Estonian gothic bears a subtitle A Dozen of Strange Tales and opens with Stained Spirits (Määritud hinged), also called a sad fantasy by the author. This tale is Õunapuu’s grotesque vision of the first President of the Estonian Republic, Konstantin Päts. A heated discussion has opened among Estonian historians in relation with the recently revealed fact that Päts had received some bribe money from Moscow; the problem is, whether he should be taken as a traitor who sold Estonia to the enemies, or whether he was a sober and sensible politician who tried to avoid senseless heroic attacks and futile losses in human lives. In Õunapuu’s story, Päts hands the Estonian Republic over to the Soviet Russia for 50 million dollars to be unconditionally used in both physical and spiritual ways. At the same time, he was tormented by visions of a skinned squirrel running ever faster and faster in an iron wheel.

The book begins with a gruesome sequence of images depicting the separation of Estonia from Europe (Päts wolfing food, the meeting between Päts and Stalin, etc.), followed by grotesque scenes about the fight for freedom (the forest brethren), and also presents pictures about the return to Europe, not neglecting the ‘kowtowing in front of ‘Prüssel’ men of power’, the communist past and the dissolving of Estonians among the aliens. The closing story of the book, Till Death Does Us Part (Kuni surm meid lahutab), is subtitled Back to Europe; here, a new husband faces the fact that the right of the first night with a married bride belongs, after an ancient custom, to a European man – baron von Mannteufel. In such a way, Õunapuu intervenes into the existential questions of Estonian independence and into ordinary everyday politics.

This collection contains also a precise psychological thriller about the relations of a mother and a daughter titled A Bright Afternoon (Helge õhtupoolik), which could also be translated as Helge’s Afternoon, since Helge means bright in Estonian, but in this story, this is also the daughter’s name.

In a word, Õunapuu’s new collection presents masterful and brilliantly visual paranoid scenes that all together could be called as fantastical fictions about Estonia.

Triin Soomets. Leping number 2. Luuletusi 2000-2003 (Covenant Number 2. Poems 2000-2003)

Tallinn, Tuum, 2004. 63 pp

One of the most interesting Estonian poets of the younger generation, Triin Soomets (1969), gives her readers the image of herself, her poetical self-portrait, in the text titled “Soomets”. This is wordplay: in Estonian, the poet’s name is a compound word, meaning “a bog” and “a wood”. She says: “I am interested in your lips as if they were the Ten Commandments,/ because I sin against most of them/ when I kiss you.”

Maybe just these verses embody a sin against the first covenant, made between the man and god, from which originates the journey of sovereign art to discover the darker, more mysterious and “boggier” half of human nature. The same is also suggested by the cover design of the book, where the author’s portrait has been blended into the shadows of blood-coloured trees. The poet as a creator is an individualist and does not tolerate the authority of god over her. We can say that Covenant Number 2 is made only with oneself, and the poet says that “the most awful covenants/ are made with oneself.”

The destructive eroticism of Soomets’s poetry has frightened critics, at the same time evoking thrilling psychoanalytical observations. Her verses of well-defined form and coherent rhymes, full of hints and unspoken images, leave many alluring openings for the reader’s fantasy, but the final truth still always slips away. Her poetry employs images referring to new romanticism, bright symbols, physical sensations, and sometimes even frighteningly straightforward erotic details. Such poetry is nothing like fragile and tender. Rather, we can sense something animal, primeval and rebellious coming from deep inside and resisting the fine cultural polish of the surface. Sometimes, this poetry is like a description of a reflection in the mirror, where the poet sees her reflection as an animal. Quite often she refers to a she-wolf or simply to a predator; the “you” to whom she addresses the poems becomes an animal with a muzzle in her dreams. But quite frequent the play with gender roles in Soomets’s poems allows us to believe that here, too, she gives us self-reflections. In such reflections, a human being is the arena for eternal opposition of antagonistic forces – desire for pleasure and destruction, dominating and succumbing to raw force, but maybe even culture and nature.

Jüri Tuulik. Linnusita (The Island of Bird Shit)

Tallinn, Maalehe Raamat, 2004. 406 pp

After Jüri Tuulik (1940) had published a voluminous and successful collection of short stories A Lonely Bird above the Sea in 2002 (see Elm 16), the same publisher recently issued a new selection by Tuulik, The Island of Bird Shit, containing short stories, but also radio plays and poetical miniatures. The author said that so many good texts were left over from the previous book that he was able to put together another one.

The Island of Bird Shit includes a number of texts written before 1990 that have been published elsewhere, and new unpublished texts. The sources of Tuulik’s work can be found on his small home island of Abruka, located near Saaremaa, and on the island of Saaremaa itself, about which Tuulik has said: “Saaremaa is not only a geographical point in the Baltic Sea – it is also a spiritual condition, which will never leave those who have experienced it.” And also: “Abruka has been made of the same material as all the rest of the world – here, too, secrets are born and die.”

The islanders in Tuulik’s books are the people, whose everyday problems are connected with the catch of fish and the weather, and whose universal problems are connected with interpersonal relations that may have difficult twists. Drinking often makes life difficult, but much heavier is the burden of having been weak or having betrayed somebody in the past.

Honesty, straightforwardness and humour are most appreciated among the islanders. The subject of many a Tuulik’s well-known stories is the relations between a man and an animal, or a man and a bird. The book opens with a story A Village Tragedian about a mongrel Nässu and his master – presented from the dog’s point of view in a racy and folksy style. Tuulik’s texts are widely popular all over Estonia just because of his folksy style and comical characters and situations. Theatrical open-air summer performances are very popular and the plays are staged in many locations. It is natural that Tuulik’s Abruka Stories were produced just on the island of Abruka.

Besides funny stories of local colouring, The Island of Bird Shit contains lyrical miniatures and reflections on the permanent values in life, and about time that runs short before one is able to realise one’s plans for life. Four radio plays are included in the book, and a TV play. All in all, Tuulik has written 26-27 radio plays, which have been performed in Estonia and in abroad. One of the radio plays has lent the book its title – The Island of Bird Shit. In this play two people meet again – an elderly writer and the dream girl of his youth, now a mother of three adult children. They are gazing over the sea towards their island, called The Island of Bird Shit, since there are only one tree and plenty of birds on this small islet. Once they had dreamed about building their home on it and living there happily ever after. Now they meet new young lovers who dream about the same.

Although it is often thought that the key to Jüri Tuulik’s success is his humour, he talks much about the general values that form the basis of human existence.

Toomas Raudam. Teie (You)

Tallinn, Eesti Keele Sihtasutus, 2003. 226 pp

Toomas Raudam’s (1947) You, an essay on Marcel Proust and James Joyce, centring on Proust, was given the Estonian Cultural Endowment essay award in 2003. Raudam’s deep spiritual affection for Marcel Proust has a long history. Already his collection of stories Writes in the Air with His Finger (Kirjutab näpuga õhku) includes two literary essays, one of which is about Proust. We could, actually, say that the whole of Raudam’s prose (see Elm 4, 5 and 9) is carried by the spirit of Proust and Joyce, containing insights into a youth’s psyche, carrying a flood of associations, penetrating the depths of memory and precisely mapping the temporal dimension, formulated in long complex sentences.

You includes long quotations from the authors under discussion and cites well-known researchers. Raudam has managed to avoid report-like presentation; the book is a dedicated and competent study with an awesome list of references. Besides Proust and Joyce, it also touches upon several other writers of the period, longer passages are devoted to Vladimir Nabokov and Franz Kafka.

The discussion of the subject is not rigidly chronological and does not claim to be an exhaustive overview; it mostly focuses on “how something very small, Marcel, I, gave rise to something very large – OUR LIFE”. YOU (denoting his special objects, Raudam usually uses capital letters) means also US in Raudam’s approach, or in other words: THEY have sensed and expressed something also for US.

Raudam enters the spirit of Proust’s world rhetorically, too. His language is refined, full of word play and imitation games. Since HE is also US, he weaves certain autobiographical moments into his text and makes the academic presentation more belletristic.

Naturally, he had had to translate quotations from Proust’s texts, and he also used different Estonian translations of Swann’s Love and Sodom and Gomorrah. In such a way, Raudam’s You is not an academic study, but an essay on Proust (and Joyce and others), and on how to approach Proust, how to understand the great Frenchman and with him, how to understand oneself.

Viiu Härm. Keegi teeline (A Wayfarer)

Tallinn, Varrak, 2004. 744 pp

Viiu Härm. Õhuaken (A Small Window)

Tallinn, Varrak, 2004. 280 pp

Viiu Härm (1944) studied to be an actor and she has had a short but successful stage career. As a poet, she belongs to the margin of the canon of the famous generation of Estonian poets of the 1960s, continuing the strong tradition of Estonian women poets that reaches back to the era of folk songs. To mark her 60th birthday, she collected her work like ripe fruit into one large volume.

Härm published her first collection of poetry in 1973; it was followed by a few other collections, but for the next twenty years the author was silent. This voluminous book verifies that the poet had not stopped writing – a large number of these poems have not been previously published. The title of the book indicates that she identifies with a wayfarer, a passer-by. Reading her first poems anew, we find that those poems, full of nature experiences, childhood memories and dreams of happiness still affect us in the same tender and fragile way as they did almost forty years ago. Later, her world of poetry followed the life of a woman; she wrote about girlhood, maturing and becoming a grandmother. She poeticises a woman’s life, talking about continuity, common joys, sadness and resignation. She focuses upon the life of a child, a girl, a mother, and especially, a grandmother, giving a powerful symbol of the life of Estonian women.

Her collection includes a number of dedication poems, among others, to great Estonian women authors Lydia Koidula, Marie Under and Betti Alver. On the background of modern Estonian poetry, Härm’s work differs from that of the others by its warmth, its special sensitiveness; there is much more hope in it than sadness about illusionless routine or cold weariness; she talks about persisting in spite of pain and hardships.

A Small Window is Härm’s second novel; (about the first one, The Second Take, see Elm 11). This is a slightly autobiographical work about a hospital, written from the viewpoint of a young girl, a student, Riine. Härm describes a closed world where the sounds from outside can be heard only very vaguely. The cause of Riine’s illness cannot be found; the mood of the sensitive girl swings back and forth between hope and hopelessness. The world of the hospital is limited, allowing only a narrow range of impressions and experiences; the gulf between the worlds of the ill and the healthy is wide. The scene of the novel is laid in the 1960s or 1970s, but Riine lives almost entirely in her own small microcosm, confined by her illness, and does not notice the flow of time. This book is written with a master’s touch, but it stands quite apart from the vigorous literary life of the present day and the signs of time.