Jaan Kross. Kallid kaasteelised (Dear Co-travellers)

Tallinn, Eesti Keele Sihtasutus, 2003. 719 pp

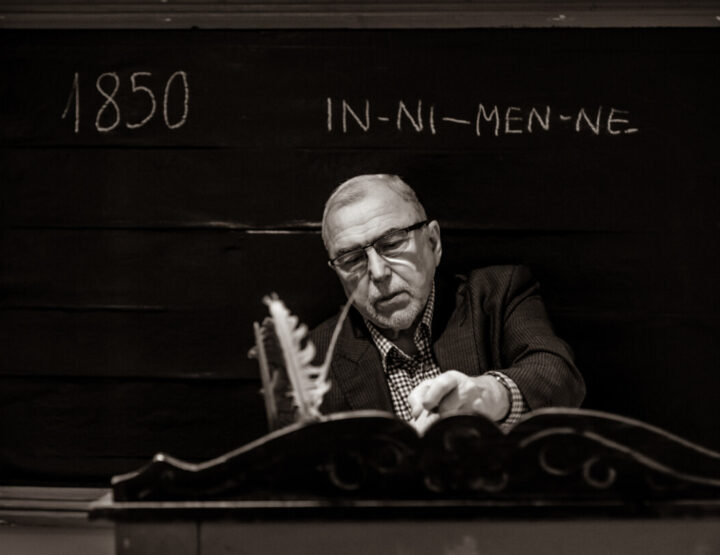

The publication of Jaan Kross’ (1920) memoirs at the end of 2003 was a literary event. The book has topped best-seller lists and it has been much discussed by critics as well as by the reading public. Dear Co-travellers is undoubtedly one of the most representative memoirs authored by a writer in the past decade; it is a kind of criterion against which the memoirs of other contemporaries will be measured. A number of artists and scientists, and also people repressed by Soviet power, have published memoirs recently. In addition to being the stories of certain people’s development, all these layers of memory reflect the bygone era.

Jaan Kross’ present book is, actually, only the first part of his memoirs; hopefully, it will be followed by a second part. At the same time, it is a unified work, an extensive chronicle of the era and an intriguing self-portrait, covering the period from the writer’s youth up to the beginning of the 1960s.

Kross has been writing about his own life and history for many years. In his works of fiction he has assumed a number of aliases, mixing reality and fiction and changing scenes, all the time moving away from the fictional and approaching the documentary, or, rather, approaching the traces of documentary in the memory.

At the beginning of 2003, Kross published his university lectures under the title Autobiographism and Subtext (see Elm 17), where he throws light on the autobiographical layers of his novels. In Dear Co-travellers he also refers to those of his books in which he discusses some events that have actually happened. His memoirs do not offer confessions of the development of a young man, but rather, they can primarily be called political memoirs, since they have a very clear political subtext. Naturally, Kross presents his life story in relation to historical events and his memoirs are an excellent history lesson for those readers who have no experience and only vague ideas about the reality of the Soviet empire. The author touches only briefly upon his childhood and youth, rushing on to the period which began in 1939 and initiated events of crucial importance in Estonian history. At that time Kross was reading law at the University of Tartu. A large proportion of the book is devoted to the time when Kross was a political prisoner in the northern region of the Soviet Union – in the Komi ASSR – where he at first worked in a labour camp coal mine. Later he was deported to Siberia, where he worked in a brick factory. Representative and telling scenes of the reality of a socialist state, of its ridiculous economy and of the total fear it instilled in its citizens are presented in a memorable form in the section that describes the author’s life after having returned to the Estonian SSR. The memoirs end when the author is given a flat in the new “writers’ house” (a residence built for writers) in Tallinn in 1962. In spite of all his difficulties, the previous repressee became a writer.

The idea of Kross’ memoirs is to stress the historical injustice of the sacrifice of Eastern Europe after the end of WWII. The main prerequisite of a prisoner’s liberation is that he survived his imprisonment; the author remembers many cases where imprisonment and the administration of justice were totally farcical. Kross repeatedly draws attention to the fact that, at that time, none of the leading powers of the world were interested in the restitution of sovereignty to the Baltic states, and that the treachery of the Western democracies condemned half of the nations of Europe to live in isolation for fifty years. “I have to ask unceasingly, who was ready to shoulder responsibility for the fact that half of the nations of the whole continent /—/ had to live with their faces trampled into the mud for half a century?” (p 333).

In a witty text, demonstrating the whole range of his masterly style, Kross tells his own life story and, along with it, the story of Estonia in the first half of the 20th century, as an account of treason and paradoxical survival.

Jaan Undusk. Quevedo. Näidend 12 pildis (Quevedo. A Play in 12 Scenes)

Tallinn, Perioodika, 2003. 123 pp

Jaan Undusk is an outstanding literary critic and writer, whose scientific production has so far been more numerous than his literary woks. All his books have attracted equal attention (see Magical Mystical Language, Elm 8). Aspiration for magical tension characterises also Undusk’s literary texts – his short stories, a novel Hot (“Kuum”), which can be treated as an essay about young love, written in the format of the novel, and his plays, which are his latest passion. He made his breakthrough into drama with Goodbye, Vienna (1999), which had success on the stage. The fact that Quevedo was by far the best entry at the play-writing competition in 2003 and won the first prize came as no surprise – when Undusk takes part in a competition, he wins.

Similarly to Goodbye, Vienna, Quevedo is full of intellectual and erotic tensions, enhanced by figurative language and aphorisms, which result in a real fireworks of philosophical dialogues. The hero of the play is a Spanish genius of the 17th century Francisco de Quevedo (1580-1645), the eternity, death, beauty, spirit, and naturally, power are its subjects.

The main intrigue of the play is the contradiction between the poet and politician Quevedo and the Prime Minister of the Spanish kingdom Olivares. This is the eternal struggle between the spirit and the power, resulting in different ways of conceiving the social responsibility of an individual, but it is also a duel between two powerful gamblers. The struggle between Eros and Thanatos adds spice to relationships described in the work. In Undusk’s world, suffering is a pleasure, all his heroes are characterised by the fear that the pleasure might end, and they fear fulfilment and satisfaction that would cancel the pleasure. Undusk contrasts closure and openness, the general and an individual’s aims and pleasures, the metaphysics of ugliness and the beauty of expectation, and values unceasing movement. The scene is laid in the 17th century, but numerous hints refer to the universality of the subject. Quevedo and Olivares will keep confronting each other in the infinity, and Quevedo’s last question “I cannot comprehend, why they will envy and imitate us” can be interpreted both in an ironic and philosophical key. The book closes with Prof. Jüri Talvet’s informative overview “Quevedo redivius”.

Rein Veidemann: Lastekodu (An Orphanage)

Tallinn, Eesti Keele Sihtasutus, 2003. 397 pp

Rein Veidemann (b. 1946) is a well-known literary critic, journalist and politician, and Professor of Estonian literature at the University of Tartu, who has published several books of criticism and autobiographical essays.

An Orphanage is Veidemann’s first novel. The book can be seen as a nostalgic retrospective, a story of a mid-life crisis and a passionate and uncompromising deliberation on the crucial values of life. This is a baroquely saturated pretentious text, intertwining fiction and documentation. The novel is dynamic, full of excitement, love and death – everything that would fascinate a reader. It contains intertextual and autobiographical links, romantic irony and elegiac nostalgia, and reflections on the transcience of life, emphasised by lines of poetry by Andreas Gryphius.

The first person narrator, Andreas, comes to Pärnu, the town of his childhood, to take time out to reflect upon his life, but as a journalist he must also write about an orphanage that is in danger of closing. This is the oldest orphanage in the Baltic countries. Andreas grew up next to it, and the orphanage became a part of his own and his friends’ youth and life. The town council has submitted to the will of a noveau riche businessman and sold the building. Andreas’s childhood friend Viktor, who also grew up in this orphanage, has asked Andreas to come and help save the orphanage and their common past. The book mixes the fates of the post-war generation, the testimonies of the pre-war generation, who found themselves in the tight grip of the totalitarian state, and the confessions and introspections of the protagonist. Although the orphanage has given the novel its title, and also accelerates the plot, the orphanage itself can be understood as a symbol, and a few memories related to this institution mostly allow the author to ruminate on the meaning of space, etc. Veidemann’s orphanage is not a Dickensian horror, but rather a real home for orphaned children, which has offered safety for many of them and saved them from the worst.

An Orphanage can be primarily defined as a novel about Andreas Wiik. Andreas, who has come to clarify the intrigues initiated around the closing of the orphanage, also re-examines his past and attempts to sort out some private affairs. A short romance brings him together with a young girl, Stella, who is the same age as his own daughter, and allows him to feel that he is still competitive in his masculinity. He also meets Berit, his long-time sweetheart, and is sad to discover that this relationship, which had meant so much to him for such a long time has irreversibly withered away. Still wishing to search for the inspiring truth and elevating passion, he has to admit that the only thing he can do is to poeticise the somewhat bitter resignation of his memories. An Orphanage is a novel about the generations of the second half of the 20th century who had to follow the changing of the world. The author’s central theme is that we are facing the past, that the present is fading into oblivion, or withdrawing into memories.

Eeva Park: Lõks lõpmatuses (A Trap in Infinity)

Tallinn: Tänapäev, 2003. 224 pp

In her third novel Eeva Park (1950) has evidently achieved just the kind of concentration and result she had been aspiring for. This intense novel has a very well-defined composition, it discusses sharp social and psychological problems, it has an engaging plot and you feel that the end comes too quickly. We could say that this is the very novel that many writers dream about writing, and these kinds of problems have been overlooked for too long. But still, this novel has not caused as much excitement in literary circles as several other books also published in 2003.

A Trap in Infinity is about the trade in human beings, prostitution, but also about children in the streets, about human relations and about the limits of tolerance and permissibility, both in life and in art. The first person narrator, a young woman in her twenties, cowers in a half-burnt house among outcasts, remembers past events and hides some kind of secret. She is also planning something. In due time her story, which is at the same time trivial and frightening, comes out. She had met a young and handsome rich man, fallen under his spell and, dreaming about the good life, had gone with the man to Germany to sell some rare stamps, which she had inherited. But the man she fell in love with sold not the stamps, but the girl.

The author spares her readers the brutal scenes of everyday life of a sex slave; we get some glimpses of it only when the protagonist recalls some fragmented memories. She manages to escape with the help of dollars that came from another girl who was killed in a similar attempt. She was in Berlin, alone and without documents, and finally returned to Tallinn. Now, her goal is revenge. The novel ends when she has achieved her goal. A group of people party on a tourist farm; in earlier times, she herself could have been among them. Now, she keeps vigil outside, with a gun in her hand. When Lars, the dazzling salesman, who had successfully sold her, goes to swim after a session in the sauna, she pulls the trigger, and then puts the gun barrel into her own mouth. All that had once been is burnt to ashes.

This novel is a challenge to those who, either cynically or short-sightedly, talk about prostitution as a form of enterprise that needs regulation. It is also a warning to young girls. It could be said that the road that leads to prostitution in a post-socialist society is often even more trivial, the deals are even cheaper, fewer words are wasted on the subject and the social background is even clearer. A Trap in Infinity could also be called a psychological thriller that cuts deep into an abscess of society, and keeps its readers enthralled to the end.

Mats Traat: Islandi suvi (The Iceland Summer)

Tartu, Ilmamaa, 2003. 184 pp

Mats Traat (b. 1936) is a classic of Estonian literature, who has been on the scene for forty years. During this time he has published a large number of novels, short stories and poems. Traat is predominantly a realistic writer, a polyphonic narrator with a remarkable skill for generalisation, a creator of exact images, who mostly delves into the history of the Estonian nation.

The Iceland Summer continues the portrayal of remarkable men and women in Estonian history, initiated in his previous collection of short stories Carthago Express (see Elm 7), to offer, through a sketch depicting some turning point in history, insight into the topical questions and the way of thinking of a certain era. Traat attempts to restore the past, its spirit and also its morals, beliefs, dreams and disappointments. This collection contains seven short stories, the longest of which is the title story. Most of the stories are set in the last quarter of the 19th century, the period of national awakening; although some of the stories are set in the early 20th century. The story “The Ancestors’ Shadows” features three characters – the author’s grandfather, Alexander von Middendorf and Jakob Hurt. The future collector of folklore, Jakob Hurt, was a tutor for the family of the scientist A. V. Middendorf. But the plot develops, not in a classroom, but in the kitchen of the manor, and the above-mentioned trio only help to specify the time and place of the story. The action is centred on a violent cook, suffering from toothache, who hits a groom with a crowbar and almost kills him. A still more exact insight into the way of thinking (and spiritual life) of the peasants can be found in the best story of the book, “Court Mirror”. It is probably based on old documents of a court of justice, which results in a very deep, exact and true-to-life story with a well-composed structure and a clear theme. The most skilful stories of the collection reveal scenes from the peasants’ life, centring on some episodes that differ from the everyday routine. The stories written about intellectuals or Baltic-German nobility are full of factual material, with the author aspiring to reflect many problems of the period through the inner monologues of the characters. The title story “The Iceland Summer” introduces the granddaughter of Jakob Hurt, the pianist Helmi Viitol, who recalls episodes and people of Hurt’s family, but also expresses a sensitive person’s yearning for unimaginable experience. Traat’s short stories, besides being a real literary success, help us feel the course of history and our place in it.

Kauksi Ülle. Uibu (An Apple Tree)

Võro, 2003. 151 pp

Kauksi Ülle (1962) is an author who applies feminist discourse in her works, and attempts to join the present day with the heritage of the past. Having already started intertwining the present and the past in her poetry, she now keeps mixing them in her prose, especially in her novels. Her second novel An Apple Tree continues the tradition of her three earlier works of prose (the novel The Boat (1998), and two collections of short stories). An Apple Tree, subtitled A Story of a Fine Maiden, or of a Messed up Small State 1990-2002, discusses the everyday life of a jobless woman living in a slum, and trying to make ends meet and feed and clothe her children. The plot is mixed with southern Estonian myths and the song of an apple tree. The book is written in the South Estonian dialect.

The action in An Apple Tree takes place over a dozen years from the early 1990s to the present. At the beginning of the book, the characters move through the time of transition, receive foreign food aid, etc.; the protagonist Anna, who works as a radio broadcast editor, soon loses her job. The material crisis in society is accompanied by a moral crisis: people copy foreigners in all spheres of life, losing their own traditional ideals (for example, they sell an ancient sacred mountain to a gravel processing company). Since many only want to improve their economic situations, and others can no longer cope with their hard life, fewer and fewer children are born.

The novel consists of 13 chapters, which often draw parallels with the life of recent years. Each chapter opens with an excerpt from Kauksi Ülle’s own ballad “A Fine Maiden” (from the collection Golden Woman, 1997), based on many versions of the Seto epic folk song “A Daughter into Water. A Fine Maiden”. This ballad is the cement that holds together episodes of Anna’s life, mostly given as inner monologues, full of memories and folk songs. The ballad tells of the custom of killing new-born girls in patriarchal societies; in the song, such a girl becomes an apple tree.

Although a child (a male child) is born in the first chapter of the novel, the book is not about the life of the child, but of his mother. Anna has to fight against the crises and routines of everyday life. She wants to be a creator and a singer in the tradition of her female ancestors. She wants to be a preserver of traditions, a housewife and a loved woman, but often feels that she has no place in life. She compares herself to a frostbitten and broken apple tree and is worried about the ripening of her fruit and about spoilt fruit. An Apple Tree is, however, not consistent feminist protest, nor is it only social protest, although it contains the features of both. The issue of a woman’s self-fulfilment is crucial to the protagonist. Men leave Anna’s life, and it seems that they are utterly unreliable. The feminist approach is still rather inconsistent and the social sharpness of the book is somewhat dimmed by the fluctuations in Anna’s choices.

From a feminist point of view, even the experience of foremothers reflects a negative message – daughters are not wanted, they are “taken to the water” (drowned). In some of the songs, the wife is murdered when her husband gets bored with her and the children. The modern woman at least does not have to drown her unwanted child, as in the songs, since she can have an abortion.

An Apple Tree discusses, in an original manner, the problems that many Estonian women have to face: how is it possible to raise children, when they cannot rely either on their men or on the state. The last scene of the novel is, however, full of optimism – the broken branches of the apple tree have budded and new apples are growing.

© ELM no 18, spring 2004