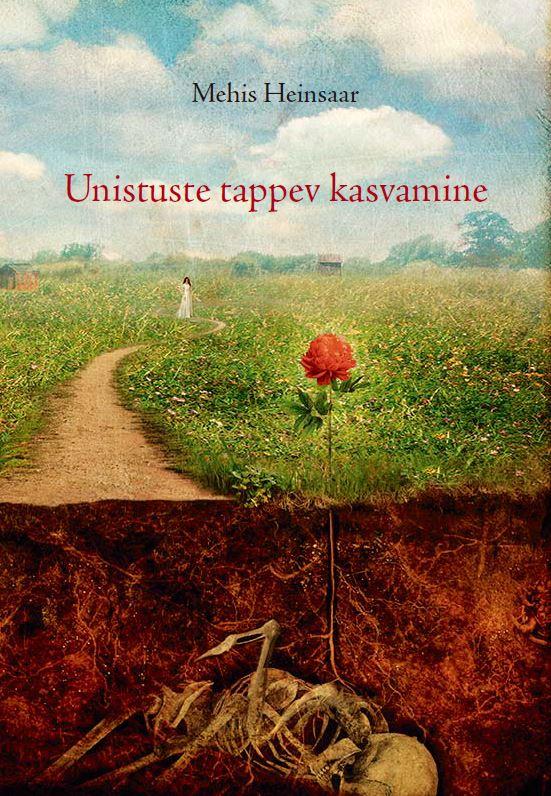

Mehis Heinsaar, Unistuste tappev kasvamine (The Killing Growth of Dreams)

Tallinn, Menu Publishing, 2016. 232 pp

ISBN: 9789949549245

Mehis Heinsaar (1973) is inarguably a magical realist, but this doesn’t mean he is in any way a product of 20th-century literary trends, a copy, or an imitator. Rather, he is a journeyer in a magical world, the map of which somehow coincides with Estonia’s own – although not so much today’s map as one of some enchanting, bygone, fairy-tale Estonia.

Unistuste tappev kasvamine is Heinsaar’s fifth short-story collection, in addition to which he has written one novel, one short-prose work in miniatures, and one collection of poetry. When he made his entrance onto the literary scene, a new wonder-child phenomenon transpired: even as a very young writer, Heinsaar scooped up almost every Estonian literary award for his first books. His first novel Artur Sandmani lugu (The Story of Artur Sandman, 2005) was treated somewhat unfairly by reviewers in my opinion – at the time, critics latched onto Heinsaar’s fantastical world, which had worked so well in his short stories and miniatures. Reviewers felt that Heinsaar’s dream-like world, with its constant metamorphoses, did not hold together well enough in a novel-like way; that it insufficiently served the story…

Yet, that particular worldly creation (both then and today’s) is Heinsaar’s ingrown way of seeing things. How often we demand that writers have their own voice! And how often we tend to accuse of repetition those, who have found that voice. Heinsaar is the kind of writer (alongside other magical realists, perhaps?) who is always clearly recognizable. Quite many devoted fairy-tale fans are unable to refrain from reading his works. They are like literary LSD or a journey taken with a magic mushroom – a fantastical vision of the world, which heals the soul. In Heinsaar’s new work, he has shifted back towards longer forms of writing, which lets us be swept away into the enchanting unknown down his very unique current. Has Heinsaar changed significantly or found a completely new linguistic style in Unistuste tappev kasvamine? Nope! But his whole former arsenal is present in a special and strong way.

Firstly, there is loneliness. Almost all of the characters in Heinsaar’s world – even if they find love or an old witch, to whom they fall victim – are initially alone, solitary. Life’s great questions lie before them like treasure maps or riddles. They don’t gain ultimate closeness or a solution to their troubles from other characters. One of the most beautiful love stories in Heinsaar’s latest book goes like this: every time after making love, a woman falls asleep for several weeks, and her husband knows that in her dream-land, the woman is with someone else – that she is the mother of several children somewhere far away in a shepherd family, and… But she always returns from her dream. The husband waits for her, watches over her, and helps her to re-adjust once more. And they are happy, in a strange way. But at the same time, he is also still essentially alone. He is in a state of waiting. Many of Heinsaar’s characters are waiting for something, but for the most part, they must personally make the first move for anything to happen. And they must do so in a dream.

Secondly, there is an adventure or journey that may be shackled to a curse the character suffers for his or her whole life; or may lead us to the smidgen of happiness we’ll have for the rest of our lives, or to our lost vitality, or… A large part of Heinsaar’s adventures are kicked off by inner need; by disquiet. His characters are propelled onto their paths because something perturbs them; something calls to them. It might simply be a feeling that sets them on their way; some prophecy or a quest for happiness – but it also might be absolutely real interference by the magical world that leaves them no chance, no choice… The adventure might lead them to a fairy-tale forest or to bizarre Estonian communities, which even while appearing completely realistic on the surface transform into fantastical places inhabited by bizarre people with bizarre maladies… Because, yes – loners and roamers are often eccentrics. So, we could say that on a larger scale, Heinsaar is an eccentrics’ writer.

Thirdly comes his fairy-tale-teller’s style – a certain calm, poetic observer’s manner, from which the speaker himself (sometimes as narrator; sometimes interrupting third-person characters as the author) is never absent. He is a wandering storyteller who truly drifts through those tales. There are questions of human fate. There is a dark, but simultaneously childish and natural eroticism.

In the book’s title short story, the dream of love helps an electrician infatuated with a woman transform into a rain cloud while standing beneath high-voltage wires, thereby (falling as magical rain) allowing him to secretly share his love with his beloved… True, the deception – the illusion – ultimately ruins lives and leads to failure; i.e. the magic doesn’t last. But occasionally, what matters isn’t magic’s persistence – its eternal accessibility – but rather the possibility of it. We love because we know that the magic of love exists and is possible, but it can’t be obtained all the time. We can’t live in a magical high endlessly.

In short, Heinsaar’s effect may be like that of a drug that douses the world in bright colors. There are dark moments among his stories; “bad” trips, so to say. Still, I am enchanted by his childish belief in fairy tales – everything really is a little magical. And in Estonia, Mehis Heinsaar is one of the greatest writers of our generation – what can you do. One of his characters remarks somewhere that the other side of our lives is like the dark side of the Moon – almost like a secret at first, but when we arrive at it… I certainly feel like I’ve personally arrived at mine – at the dark side of my Moon. In order to get by there, among the lunar seas and mountains, one must have one of Heinsaar’s maps – one of his books – in tow…

Jürgen Rooste (1979) is a poet, journalist, and one of the most renowned Estonian writers of his generation. He has published fifteen poetry collections and received the Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Award for Poetry on two occasions, among many other literary awards.