The collection Tuulelaeval valgusest on aerud – Windship with Oars of Light, subtitled Estonian Modern Poetry, brings together poetry written over nearly seventy years. All in all, it includes nine Estonian poets, whose careers span a greater part of the 20th century. The selection is necessarily limited, with no pretensions to all-inclusiveness, yet is representative of the core of the contemporary Estonian poetry canon, starting with two poets of the legendary Arbujad group of the 1930s (in English, the group has been called Logomancers by the American-based scholar Ivar Ivask, while the preface by the young literary scholar Lauri Sommer prefers the term Soothsayers). Their aesthetic criteria, which have set the tone for the mainstream of 20th century poetry in Estonian, are introduced by Betti Alver’s sonorous poems of intellectual intensity and Uku Masing’s occasionally cryptic and oblique verse of religious sensibility that also lends the collection its title.

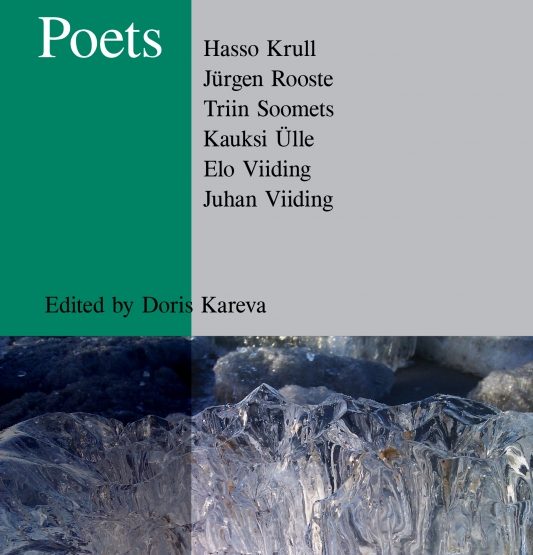

Another nucleus that is related to a significant period in literary history is provided by the so-called “cassette generation” of the 1960s, represented in the anthology by Jaan Kaplinski, the most widely translated Estonian poet, and Paul-Eerik Rummo, whose latest achievements fall in the realm of poetry translation. To these contemporary classics a handful of no less significant authors from later decades is added: in a somewhat reductive manner we might say that the 1970s are personified by the tragic jester Juhan Viiding, and the 1980s are represented by the sacral clarity of Doris Kareva, with Tõnu Õnnepalu and Triin Soomets expressing the different facets of the mixture of ever-changing nature and cultural decadence, religious feelings and sexuality in the last decades of the past century. The original talent of Artur Alliksaar, officially nearly neglected during his lifetime, but inserted into published literary history by a major posthumous collection that appeared a couple of years ago, has found its place between Alver whose oeuvre is already available to the Estonian reader, and Masing, the publication of whose numerous manuscripts many are still awaiting.

The thematic preferences in making the selection seem to have been the universal, the spiritual, the wondrously and painfully human. The relatively small number of authors included supports the overall effect of crystalline condensation. What seems regrettable, though, is the deliberate neglect of the translators’ role in compiling the anthology, although the editor’s introductory note expresses words of thanks to both “visible and invisible” translators. The note also suggests that in several cases the translations have ultimately emerged as a result of co-operative effort and thus presumably do not illustrate the individual styles of the particular translators involved. All in all, however, the collection does not testify to a single governing principle that might have guided translating or editing the texts, but rather represents multiple divergent approaches, as is only to be expected from a team of twenty-one people who have listened to and mediated such different poetic voices. The strategies employed range from metrical – although not strictly homometrical – rhymed translation, as found in, e.g., some poems by Alver, Rummo and Viiding, to less strictly formal image-centred renderings, especially suitable for the free verse prevailing in the poetry of the second half of the century – a strategy that obviously has paved the way for the wide publication of Kaplinski’s poetry.

For an Estonian reader, the translations resulting from the latter strategy may even prove an eye-opener as to those aspects of the poems that may be overshadowed by other ones, dominant in the original. This applies, for instance, to Alliksaar, whose verse in translation has been stripped of most of the prevailing sound patterns of alliteration and assonance so characteristic of the original poems. Yet the loss through translation serves to highlight the strength of the poet’s images. At the same time, not all poems survive equally well in a foreign language. The loss of Viiding’s linguistic ambiguity, punning and ingenious rhymes transforms the power of some of his texts to an extent that makes Lauri Sommer wonder in the introductory comment whether it is at all possible to render his poetry into other languages.

While the question of the ability to translate poetry surfaces every now and then without receiving a definitive answer, and the multiplicity of possible approaches to translation has once again come into focus in literary debate in Estonia, Windship with Oars of Light serves to illustrate these issues for a reader who has a command of both Estonian and English. For someone reading in only one language, it offers an intriguing glimpse through a doorway that exposes a fraction of modern poetry written in Estonia and, it is to be hoped, eventually invites one to proceed even further.

© ELM no 13, autumn 2001