According to US literary critic Shoshana Felman, insanity is an obsession of contemporary literature: stories being told are almost exclusively those of madness. Is this the case with Estonian literature, also?

The New Devil of Hellsbottom (Põrgupõhja uus Vanapagan), the last novel by Estonian literary great A. H. Tammsaare (1878–1940), was published in 1939. The author once explained to an astonished journalist: “It may be true that at first, it appears to the reader that the author is insane, but as soon as he reads on, he finds that he himself is insane. And when he reads even further, then it appears to him that the whole world has gone insane!”

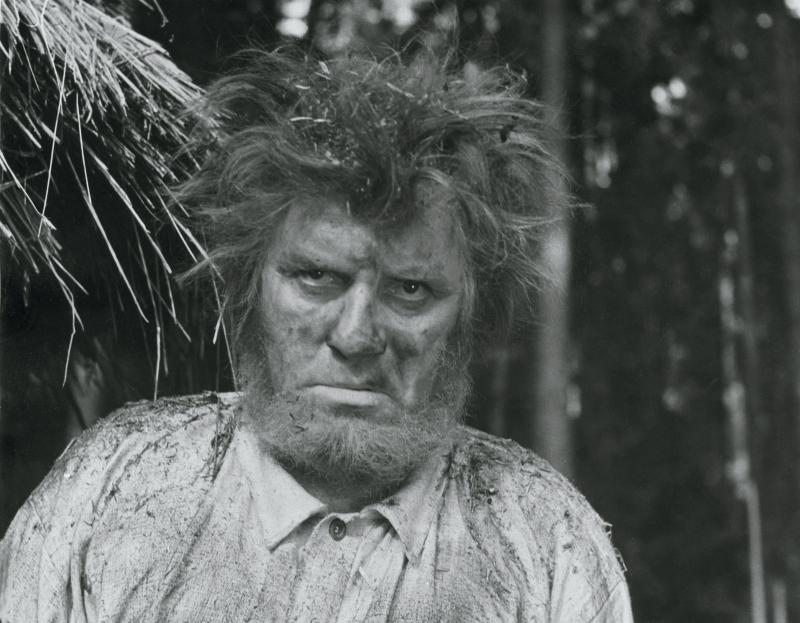

The New Devil of Hellsbottom is Tammsaare’s most mysterious and highly social-critical novel. In it, the author is intrigued on the one hand by theological questions (Does redemption exist, or is it possible?), and on the other by what becomes of a society being led by greed; one that no longer possesses ideals or spiritual foundations. The main character, Jürka, claims to be Vanapagan (the “foolish devil” of Estonian folklore), who wants to continue running Hell and has therefore come to redeem mankind – this in order to prove it is possible to live in a manner that one achieves eternal bliss. Naturally, the other characters assume he is off his rocker when they hear this.

Tammsaare-era readers were unaware that the author also wrote a prologue to the novel, in which he reveals the backstory. Specifically, Jürka goes to speak to St Peter in Heaven, where they agree that if he manages to live his life and achieve eternal bliss, then he can keep running Hell. Readers of the time thus faced a conundrum: they hadn’t a clue whether Jürka was merely a dim-witted peasant or the true Vanapagan. It was up to each reader to decide for him- or herself.

Why did Tammsaare decide not to publish the prologue? Perhaps it was to test readers. If the reader deemed Jürka insane, then his or her own value judgements were also misaligned. For in spite of his “insanity”, Jürka embodies the almost sole element of normality in the novel – he attempts to live according to the right ideals and value judgments at the same time as most of the other characters are heartless and unethical. On the one hand, Jürka is like Faust turned upside down (whereas Faust sells his soul to the Devil in order to achieve his aims, Tammsaare has the Devil sell his soul to God) or a dislocated Christ, who declares truth and wishes to redeem humankind. On the other hand, Tammsaare uses Vanapagan to criticise an upstart society that esteems vapid and bad-natured individuals while simultaneously regarding someone who lives in the name of ideals as “bizarre”. Either way, by writing the novel – published on the eve of the Second World War – Tammsaare intended to point attention towards his view that everything in society had seemingly flipped upside-down; that the world had gone insane. And as history showed, he was right.

One “madman” character somewhat similar to Jürka is the Livonian nobleman Timotheus Eberhard von Bock of Võisiku Manor, who appears in the novel The Czar’s Madman (Keisri hull, 1978) by Estonia’s most internationally-renowned writer, Jaan Kross (1920–2007). In Von Bock’s case also, readers and the other characters are unsure whether the man is pretending to be insane or is indeed mad. In truth, Von Bock represents the same kind of social-critical attitude as Jürka, since he is likewise someone who strives to behave according to his ideals – and who is therefore classified as insane in the eyes of the rest of the world. Kross’ Von Bock has been compared to Shakespeare’s Hamlet: both men’s insanity is associated with speaking the truth; both behave simultaneously provocatively and ironically in their madness. The relationship between deception and truth is a question apart in the cases of Jürka, Hamlet, and Von Bock. All three are convinced that they themselves represent the truth… or does it only appear that way to them? In any case, the figures raise the question of where the line between insanity and sound thought runs. Up to what point does a “sensible” man go along with his actions, and is progressing further in the name of his truth then perhaps “insanity”?

Yet the issue of insanity and normality has not been left to mere theoretical discussion in Estonia. During the 1970s and 1980s, one of young men’s greatest fears was conscription into the Soviet Armed Forces, which could mean being sent to the Afghan front or simply having to endure daily physical and psychological violence. Jaan Kross’ son Märten Kross (b 1970) published in 2014 The Insanity Game (Hullumäng): a novel telling how the only way for young men to avoid Soviet military service was to get themselves a “diagnosis”. This meant months, if not years of “playing insane” – faking mental disability in order to convince the authorities that one was unfit for service. It was in this very way that many Estonian cultural figures received the proof they needed from accommodating doctors.

However, the “insanity game” did not only concern young men fearing Soviet conscription. One of Estonia’s most famous writers who acquired “crazy papers” to save his life was Aadu Hint (1910–1989). The KGB found out that Hint, who was initially loyal to the Soviet regime, planned to escape to Sweden by boat in 1946, and the writer was issued a harsh warning. Literary critic Toomas Haug[1] writes: “It’s possible that after being caught with his escape plan, Hint was so overcome by fear that he saw it necessary to acquire a certificate of insanity. The writer’s home archive contains a few papers filed under the keyword “Insanity”, one of which – in Russian and almost illegibly written in pencil – is a questionnaire for one “Mikhail Mironov”. It’s possible that this was indeed Hint’s “split personality”, whose life-story he drafted while in the loony bin. Ralf Parve has recalled how one morning, Hint entered his editorial office at the Pioneer and announced that he was actually a Russian – claiming you could tell by his hair.”

It’s said that Hint pretended to be schizophrenic with terrifying believability, and he wasn’t the only person who hid himself away from repression in an insane asylum. One of Estonia’s most well-known pre-WWII novelists, Karl August Hindrey (1875–1947), sequestered himself at the Iru Care Home under a false name; not as a madman, but as being quite mentally unstable. Hindrey died there in the squalid conditions, and was buried in secret at Metsakalmistu Cemetery.

But those who truly couldn’t cope with the atmosphere of Stalinist terror also ended up in asylums – take for example poet and prosaist Jaan Kärner (1891–1958), who suffered an actual mental disorder that developed in 1946: he began sensing he could hear in his own home everything being spoken about in the government. Or short-story writer Peet Vallak (1893–1959) – his inability to come to terms with conditions of Soviet occupation brought mental ruin along with brain damage, which crippled his ability to live, and as an ultimate consequence of which he died. Communist poet and Deputy Secretary of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Estonian SSR Johannes Vares-Barbarus (1890–1946) could not mentally endure the pressure from Moscow, either, and committed suicide.

Perhaps the most legendary “insane man” of Estonian literature is coincidentally one of its national treasures – poet Juhan Liiv (1864–1913), whose extremely sensitive psyche shattered under life’s pressure. Liiv encountered delusions of royal heritage (a call to the Polish throne), chronic paranoia, heard voices in his head, etc. His classic story The Shadow (Vari) depicts an Estonian peasant, who suffers a severe state of confusion after being flogged at the local manor. In Liiv’s patriotic lyricism, his illness and personal tragedy are heightened into worry for the fate of his homeland.

Estonian literature has also had its own “shrink” – psychiatrist and prosaist Vaino Vahing (1940–2000), who enriched the country’s literary scene starting from the late 1960s. Vahing’s parlour was famed for its experiments, which included human psychological testing and the sampling of psychotropic substances. It was through Vahing that various psychoanalytic ideas and corresponding literature spread and influenced the development of Estonian literature.

Perhaps this brief bout into the discourse of insanity may be concluded with a quote from Tammsaare, likewise. In Volume II (1929) of his Truth and Justice pentalogy, school headmaster Maurus imparts the following words of warning to his pupil Indrek: “You think that you’re not the one who is crazy, but rather it is those others, and then it is certain that you are already insane.”

Doubtless it is worth keeping Maurus’ words in mind.

[1] Haug, Toomas, 2010. Lahkumine tuuliselt rannalt. Aadu Hint 100. – Klassikute lahkumine. Tallinn: EKSA

Maarja Vaino (1976) is a literary scholar and the director of the Tallinn Literary Centre. Her doctoral dissertation Poetics of irrationality, which scrutinizes the works of A. H. Tammsaare, is an outstanding study of the Estonian classic.