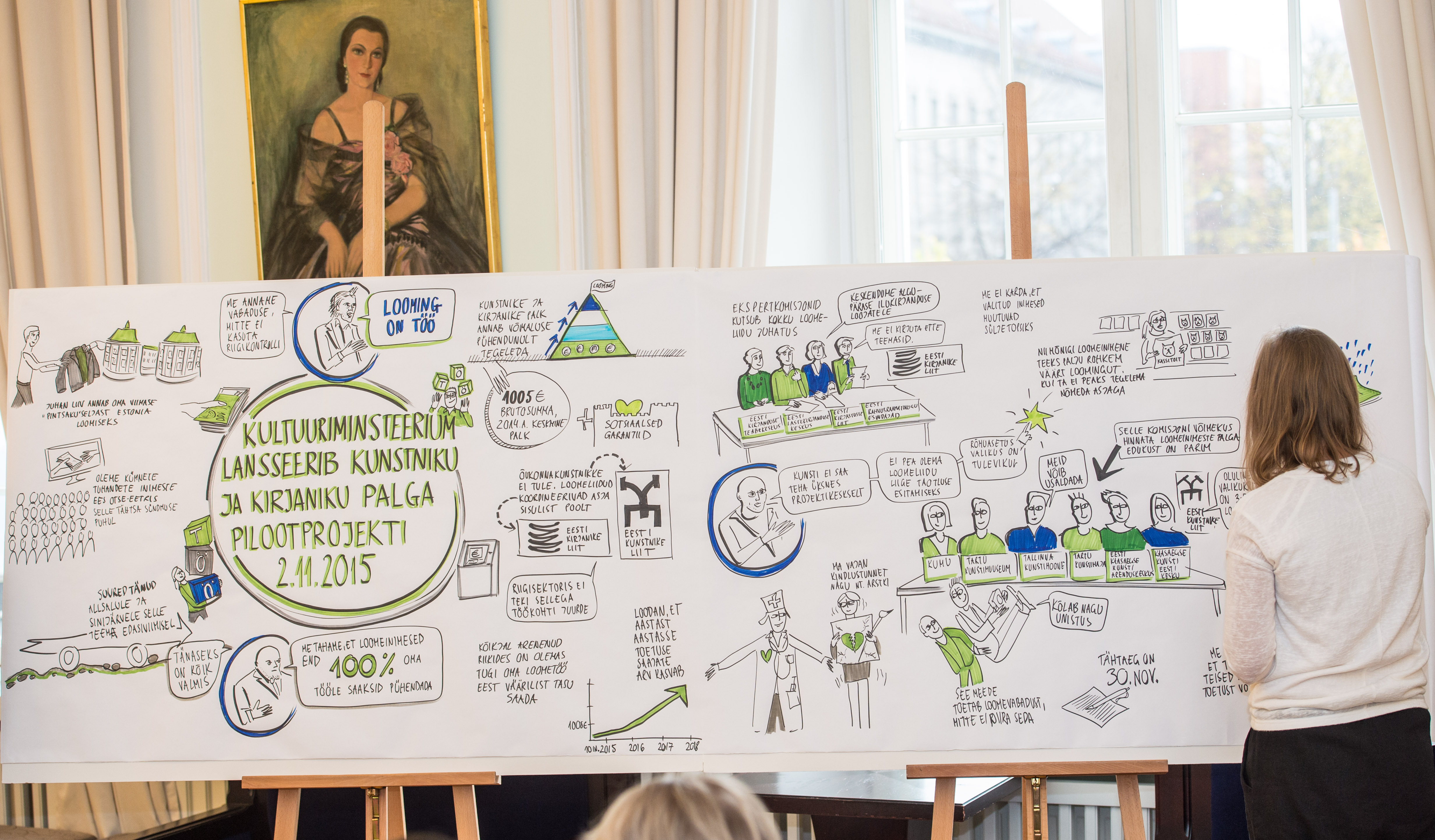

Estonia is a small country where people generally can’t make a living purely on art and literature: the market simply isn’t large enough. That’s why several years ago, a discussion sprang up over whether the state could start paying writers and artists salaries. The idea finally came to fruition in 2015, when the Estonian Ministry of Culture launched a unique pilot project: three-year salaries for artists and writers via an additional amount of government funding earmarked for creative unions.

The funding is distributed through the unions’ open competitions: selected salary recipients sign three-year employment contracts and are paid the average Estonian monthly gross salary for the year before last (€1,146 in 2016). At the same time, the salary does not apply any creative limitations or place obligations on its recipients, and all copyrights to works created during the salary period still belong to the authors. Although there are basically no restrictions, the salary does entail providing an annual overview of the recipient’s creative activities. Thus, while not especially encumbering the recipient, the regular salary, along with the social benefits it includes, provides an opportunity to write or create more freely. So far there have been three separate opportunities to apply for the Estonian writer’s salary, with 12 authors total: Maarja Kangro, Indrek Koff, Mihkel Mutt, Jürgen Rooste, Triin Soomets, Jan Kaus, Mehis Heinsaar, Eeva Park, Hasso Krull, Maimu Berg, Kätlin Kaldmaa, and Piret Raud.

Naturally, a relatively unusual undertaking such as this has been dealt a fair amount of criticism. Commentators have focused on the extraordinary details of the contract, but even more talk has revolved around the difficulty of evaluating outcomes. Discussions have likewise sparked over whether or not the desire to make a living off of literature is an extravagant and luxurious life choice in and of itself, for which the writer is personally responsible.

Still, the fact remains that the current salary recipients have already published a wealth of new works, and public opinion of the writers’ and artists’ salaries leans towards the positive. But how do those getting writer’s salaries feel? Seven of them shared whether the honor has changed anything in their lives, as well as whether their original expectations matched the reality of the situation.

Indrek Koff

Materially speaking, one extremely important change is that I don’t have to work myself to the bone for a chance to go to the doctor. And overall, it’s good to know that you won’t starve even if you only busy yourself with literature for three years. Another side of it is specifically the involvement in literature: I’d probably still have done more or less the same things, but the idea of being a “state writer” haunting my brain motivates me to better structure my activities and to undertake and finish things that otherwise might have simply remained ideas.

I had no expectations at first, only that for three years I could do what appears (at least in my mind) to be my calling: writing and translating at full speed and with full dedication. I suppose there were some little worries about public opinion, too, since the idea received heavy criticism at first. And occasionally, a question nagged at my subconscious: what if I develop an obligation block? The criticism died down and no block came. I’ve been able to dedicate myself to writing. In short, I’m grateful, and I believe that the salaried writer’s spots should definitely remain. It’s an unbelievably great opportunity for literature, in a country with such a small readership.

Mihkel Mutt

The writer’s salary has provided me with peace, freedom, and certainty. The money doesn’t allow for any luxury, of course, but neither is there a gnawing worry about how to pay the bills. There are many different kinds of creative people and, for some, living under pressure so much as favors their writing, but that’s certainly not true in my case. My creativity is at its peak and my productivity at its greatest when I “don’t have to do anything, but can do everything”. I’ve published three books in the last two years. In particular, the writer’s salary has relieved me of the need to do side work, i.e. to constantly write for the media. That’s something that writers have been forced to do at least since Dickens’s time, and something which all have cursed. When I write a column now, I do it out of free will, and not to patch a hole in my budget.

Did the initial expectation and reality match? Yes, entirely. The writer’s salary hasn’t come with any strings attached, and nothing has limited my freedom. I’ve slept better, and it’s possible that I’m more tolerant of my fellow citizens and the whole world!

Eeva Park

The writer’s salary basically hasn’t changed anything, but it has yielded an important answer. I started writing when I was a little over the age of thirty, meaning relatively late. I’d decisively incinerated all of my first attempts at the age of 16, and never intended to do what was excessively ordinary in our family: write. I kept my promise for longer than the age I was at the time, but at some point (and not at all when I had too little work to do daily, but the exact opposite), surprising even myself, I started writing at night instead of sleeping. My brother Ats, with whom I was very close, asked me what I was doing, and when I told him I’d started writing, he was incredibly shocked. He looked me straight in the eye and said: “Don’t! Quit right this instant; I don’t want things to go badly for you.” My brother was a big materialist, so perhaps the writer’s salary would have convinced him now that things didn’t go as badly as he feared when I ignored his advice.

Triin Soomets

I had no expectations for the writer’s salary. I applied without any great hopes of being chosen: I simply wanted to support the undertaking, so to say, so that there’d be applicants and those making the decisions would have people to choose from. Being selected came as such a great surprise that I had to sit down on the floor when I got the call. The reality is that I’m receiving a regular salary for my persistent work. What has it changed in my life? I’d really like to ask what would change in your life if you suddenly started receiving wages for your work. It would feel normal, wouldn’t it? At the same time, it certainly hasn’t changed anything, because you can’t write on command, or at least I can’t… Well, I can, but straight into the wastebasket. A writer will work no matter what, in almost any kinds of conditions. But I find it entirely normal and proper for it to be accepted just like any other job. Those in other professions would hardly do anything without pay, nor should they.

Hasso Krull

The salary most definitely meets my expectations. One can only dedicate himself to writing literature in two cases: if he is receiving a regular income from somewhere, no matter what stage of writing it is at the moment (James Joyce being a good example), or if he accepts conscious poverty and an asocial and bohemian lifestyle (Charles Bukowski being a good example). I’ve tried both, and I believe only the first option is suitable for someone with a family. As such, the writer’s salary is normal and as I’d expected. There are only a couple of small problems: the salary isn’t all that big, and it doesn’t last until the end of your life. So, it’s still just a milder type of uncertainty: you can’t make very long-term plans. These little problems could certainly be fixed in the future, which could lead to surprising results.

Maarja Kangro

What’s changed is that I don’t translate as much anymore. Or I almost don’t translate at all, compared to before. Translating and grants to write abroad were my earlier back-up; now, I don’t have to hassle with them. But I suppose it’s also tied to other income like book sales, etc. What’s more convenient is that I don’t have to pay social tax separately every quarter anymore. The writer’s salary is like a safety net for freelancers so they can work on projects that might not turn out to be commercially successful, but which they feel are still necessary, both for the literary scene and for society overall.

I expected to have an increase in discipline, which unfortunately hasn’t turned out to be the case: I write with the same spurts and spells of procrastination, just like I used to. The measure itself is wonderful, especially the idea of it. I’m glad that the number of salary recipients has increased every year, otherwise I might have felt guilty to be so lucky. There are far more productive writers than me.

Jan Kaus

There are two ways I can answer the question “What has the writer’s salary changed in my life?”. Structurally, very little has changed. I’ve been a freelancer since 2010, and I’ll continue that lifestyle even after having received the writer’s salary. I’ve always enjoyed the opportunity freelancing gives to boost my personal freedom, remove routine from life, and do all kinds of things: to write in all kinds of genres, from novels to librettos, and to address all kinds of topics; basically, to maintain a wide horizon. Between writing different pieces, I translate, play music, or draw and paint.

But in essence, the writer’s salary has changed a lot. To tell the truth, I regard the writer’s salary as recognition equatable to literary awards, or even more important than them. It’s a way in which the Estonian state acknowledges my work and its importance. Even more than that: through my own writer’s salary and that of others, the state emphasizes the necessity of literature. The initiative was a step with broader importance that impacts not only those receiving the support, but all Estonian writers and local literature as a whole.

***

The writer’s salary is recognition for the writer: it gives a clear signal that the person’s job is just as important as anyone else’s. On the one hand, the salary guarantees better conditions for creative work, and on the other, it helps authors to better deal with life’s little details by providing social benefits, including health insurance, which has always been a persistent problem for those who dedicate themselves to creative ambitions. Estonia’s cultural repository will undoubtedly be enriched with many more important works as a direct result of the state-sponsored writer’s salary.

Piret Põldver (1985) currently studies Estonian literature at the University of Tartu. She has been a literary critic since 2006, and works as a language editor at a publisher specializing in educational materials.