This letter was written in Helsinki, even though the recipient also resided there. It is dated simply : Good Friday, 1905.

My dear “Kameradin”!

I have taken up my pen to write to you, even though I could have said everything to you face-to-face. But I fear that in your presence the words would have escaped me, as happened on Thursday – and they must be spoken!

It is our future that is the issue. Or perhaps I should say my future. Like a dark cloud the question hangs over me: what right do I have to make your future happiness depend on me?

I dislike intensely listening to people talk and philosophise about love. I want to take it as it is: as a gift from heaven – the way spring suddenly arrives, the way the unfettered sea crashes against cliffs, the way the woods turn green, and birds, caught up in the magic of spring, sing as though they could die singing. I have yielded to the moment and allowed the waves of our springtime love to carry me away – without thinking of what lay ahead or where we would end up. I was aware only of the present; I cared only about what is, not about what would be. And I believe I had a right to take delight in living without thinking about what was to come. If someone takes a deep, long drink to quench his thirst, no one thinks of making it a matter for discussion – and similarly, I think the need to love and be loved is just as natural a thing. I was annoyed when people asked me when we’d announce our engagement and how we’d set up our household– without understanding the reason behind my annoyance. But now I know: it was an instinctive reluctance to wake up from our dreams into the prose of our future life.

Nothing can hold back the waters loosed in a springtime thaw – they follow their course, roaring and overflowing their banks. But gradually, when the first rush of spring has passed and summer approaches, they become more serene, more limpid. The surging of young blood is like that; feelings are like that – they ebb and flow like the wind and the waves. When love comes one doesn’t want to feel in part, one wants to surrender one’s whole self to it — body and soul. Great love, true love is like that. You were like that.

But joy and care walk hand in hand – they are twins. A great care-free joy lasts but a heartbeat. And I hear the tremor of a low and melancholy voice whispering in my heart: “You are playing a dangerous game!” It is the voice of reason.

Let us listen to the critique of pure reason!

We know to some extent what I am. But we know nothing at all about what I will become. There’s no better way to describe my future than with a ? (a big question mark). But a house should be built upon a rock. That’s an age-old truth. In this respect your parents are right to oppose our union. I cannot guarantee you material prosperity, even though this practical matter of the future – in the more-or-less practical “institution” which is marriage — is without a doubt a very important consideration. The prospect of withering amidst the cares of everyday life, powerless against the cruel barrage of daily hardships — this possibility has to be considered, especially if one has grown up in different, more comfortable circumstances.

If we look at my future with respect to the realm of ideas, it is not hard to imagine what it will be like. It will be stormy and windy, there will be conflict and struggle — against narrow-mindedness and apathy, against political and social slavery.

Above all, I must work for my people. That is why I am resolved to return to my homeland when I have finished my studies and to lay the groundwork there for my work. There’s strong discord right now throughout the country between the privileged class and those in the Estonian populace who have recently taken up the struggle for their right to create their own independent culture. I will of course stand in the frontlines with those fighting for my people, and my arrows will be directed – by dint of inescapable fate – at the Germans, who make up the conservative element in our land. Obviously I would be even less able than before to maintain contact with German circles, and my name (as well as yours) would become unwelcome among them. You would be in the midst solely of Estonians – a society only half-cultivated when it comes to etiquette and social graces, yet in matters of mind and spirit, much more alive and active than our Baltic compatriots — and on a higher moral plane. You would have to learn Estonian: for if I were to have a family, I would most definitely want Estonian to be spoken in my home. And my children, should I have children, would of course see themselves as Estonian.

But it is also possible that my own countrymen would begin to despise me if I were to disagree with the opinions of the majority, if I went my own way. In small countries it is easy to make a man’s life intolerable. One need only recall Ibsen in Norway and Georg Brandes in Denmark, who had to leave their homelands on account of their own countrymen. And it is possible I would be driven from the country or imprisoned if I did not bow down before those in power and they began to consider me politically troublesome.

Do I have the right to make your future happiness depend on me? Permit me, please, to add an example to what I have said: Eero Erkko and his wife! Juhani Aho writes about Erkko’s return from exile: “You can be sure they were not dealing in gold over there! I knew, even if it wasn’t from them directly, that it was difficult to get even a dried crust of bread. No matter that Erkko was editor of his own paper, as well as his own printer and procurator, and his wife worked as an office clerk, a housewife, a maidservant and laundress washing shirts – both of them toiling from morning till night.”

I recall something an acquaintance in Tartu once said: “A man like you should never marry.”

“ I too was born in Arcadia.” There is something in me too of a “restless soul” — as thinkers and poets are called. Restless souls have rarely been content with peaceful domestic happiness. Take an example from antiquity: Socrates with his Xanthippe. There are many other examples from more recent times — just to mention an idealist like Carlyle, for one, who was both a bad husband and bad father. And Goethe, Byron, Heine, Gorki – no, I could not count all the poets who were not suited for married life, for they were all wild and brought unhappiness to many a woman’s heart. Most of them actually were not married “like everyone else”. This is true among the great and the minor figures both. You can see the same thing in Finland. Let us assume that I am not quite so restless a soul – but I am still a man of ideas! I know one man of ideas in my homeland – it is the newspaper editor Tõnisson, who had an intended in his student days – she was also German, by the way — but later he gave her up, on the grounds that deep down he knew he was destined to be a man of ideas. And in the case of Kallas, I see again how little time a man like that has for his family: at most perhaps one hour (!) a day – for his work demands all the rest of his time. He once said, by the way: “He who marries does not act wisely, nor does he who does not marry.” And his wife observed: “People today are so sophisticated that they refuse to see the idyllic possibilities in marriage, viewing it rather as a drama that is in danger, every day, of becoming a tragedy.”

In my view there is only one circumstance in which a man of ideas has the right to make his beloved dependent on him: and that is if his wife pursues the same goals, if she is enthusiastic about the same ideas, if she is eager to undertake the same work, in brief: if she can be a doer, an active partner to her husband. With respect to us — we do have the same temperament – the same basic disposition; in some ways we are soul-mates; we are both subject to feelings and moods; we understand each other well, and so on. But our intellectual qualities, our ideals, the things that matter most to us in life are not in harmony the way our emotions are. In the course of everyday life, where it is not a question of feelings, but of actions, there is the danger that these divisions could easily lead to friction. You might, for example, accuse me of loving my wild and mad ideas more than you.

And that is why the quiet voice of reason speaks: “You who do not know life, you are playing a dangerous game. Think it over, before it is too late!”

This is the “critique of pure reason.” But my blood also wants to speak. You once asked me: “ Does Eino Leino plan to marry Freija?” I answered: “I do not think so, for poets do not generally marry willingly, and in any case not that young. You said: “But they can’t all be like that!” And I said: “ All of them – without exception.” And I meant it. For even my young blood rebels: it too shuns chains, even chains of roses. I want to enjoy the golden freedom of youth. Do you not want it too? Write, write, divine life! I am not yet ready to get tied down so young. I am not yet ready for babies and cradles. And besides, I already have children who are bone of my bone and blood of my blood: my poems. The thing I fear most in marriage is the necessity of behaving politely – and not being able to speak out, to say something “outragous” right to someone’s face, being obliged to socialise with people whose company I do not find congenial.

Obligations! Obligations!

This is what my blood is saying, my wild young blood. And you know that it is young and wild.

Springtime girl, there are two roads before you. One will lead you to an unknown future with a strange and sickly man who can promise you nothing. The other will take you far way — maybe to white houses where good and decent people are living – or to the blue sea, where a handsome, cheerful seafarer is waiting for you.

I do not think my kisses have made you impure. Our love consecrated us. I will think back to this spring as if it had been “ver sacrum.” The radiance of this sacred spring will last a lifetime!

*****************************

I will pose the most important question again: do I have the right to bind your future happiness to me? You have already said to me, “ Our love gives you the right.” But I ask further: is our love stronger than — death? If so, I have the right. But what if it is merely a chance joy – a bright moment of youthful wantonness – or more simply put, only the surging of our young blood? In that case I have no right.

Consequently: we both want to put our love to the test of time. Do we want to keep constant watch over our consciences in the event of changes in ourselves? We are both so young that we can wait, and we have to wait. I for one could only marry in five years at the very earliest. Let’s leave it to life, let’s let life decide. And if in the end, “ On revient toujours a ses prémiers amours” (one always returns to one’s first love), only then can we dare to take the actual step, which usually begins with an official engagement.

From now on we will be but beloved comrades to each other. In this spirit, let us celebrate together the first of May.

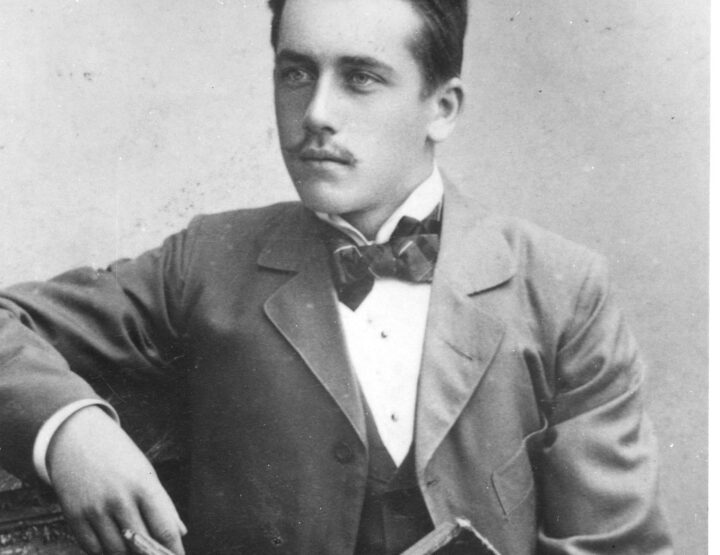

Your Gustav

Translated by Merike Lepasaar

© ELM no 16, spring 2003