pp. 14–18

II

I just wrote about Undo and Redo at considerable length, but barely added a word about Mom and Dad. As someone wrote—I can’t remember who: Memory is like a dog that flops down wherever it pleases. It was a human, at any rate; not an ape. Apart from me, are there still any other apes who can read and write? It’s possible they’ve all been tracked down, for if the seeds I sowed had sprouted and flourished, then some would’ve rowed here by now. And not just to deliver food once every two weeks, but to ferry me back to the capital. Not that I’d go with them, of course. My home is here now. I’m not the same ape I was ten years ago. My strength is petering out. I can barely write these lines and I doubt I’ll ever complete the work. But would it even be completion? Right now, it feels like writing is the final hair still holding me to this tiny island. I am endlessly grateful to Herba, who supplies me with the paper. He’s not even supposed to speak to me. Regardless, he’s helped an old chimpanzee out of a bind, though he’s an orangutang himself—not to mention descended from red apes who ended up here during the Big War. We’ve had rather pleasant conversations, albeit cut quite short—he’s not allowed to spend more time on the island than it takes to unload the crates of provisions.

My father, as I mentioned earlier, was a pastor in the Church of Manifestation, so our family strictly adhered to the principles of human proximity. Seeing as chimpanzees are as close to humans as you can get—anthropoid and nearly ape-men—he lathered up his behind every morning (lacking a tail as we do) and shaved it clean, always “bottom up, bottom up”, as he taught me. A proper behind resembled that of a human: warm, smooth, and soft; not cool and hairy. It drew ape and human closer together—every draft and accidental touch reminded you of whom you were meant to become. Anyone who had closer dealings with humans kept their bottom and tail smooth and hairless: not just church apes, but those in the party; economics, education, and so forth. I regarded the silly tradition with the utmost disdain, of course. My father looked upon me and my friends’ bristly, matted bottoms and tails with equal contempt. A couple of times, the school director took us into his office one by one and shaved our bottoms himself, sputtering angrily all the while. Usually, he just forbid us from wearing pants. Dad was incredibly embarrassed, of course. Just think: the son of a pastor in the Church of Manifestation having hairy butt cheeks . . .

“We run an elite ape school here,” the director hissed when he finished the job. “Ergo, you are an elite ape. If you cannot be one and wish to waddle around with a bottom like yours, then be my guest—go to an ordinary school and be an ordinary ape. But so long as you are attending mine, you represent not only yourselves but your institution as well.” It was also more or less the lecture he’d give, albeit without hissing, at the ceremony at the beginning of every school year. Overall, he hadn’t much else to say year after year or day after day: “This is an elite school and you are elite apes.” Ours, Albert’s Gymnasium, even had its own uniform cap, the wearing of which was compulsory. The bare heads of me and my spiritual kin yawned amidst otherwise endless rows of gold-embroidered velvet caps at every school assembly, attracting glares during the pregnant pauses in the director’s timeless speech. I remember wanting to ceremoniously burn mine after graduation, but I hung on to it all the same. So who knows—I guess it did mean something to me. Me, who never wore it once.

Although Dad occasionally growled that my friends and I looked like red apes when he saw our disheveled appearances, we didn’t know much about politics at the time. We just didn’t like going to school. School was a human invention. Red apes believed that humans were unnecessary. We believed school was unnecessary. Thus, the spiritual kinship. Red apes made everything themselves in their own country: roads, electrical grids, vehicles, you name it. As they broke down exponentially faster than products made in countries where humans were in charge of manufacturing, there were naturally red-ape jokes galore. But we, just as all young chimps believed, showed them what apes are truly capable of doing. There was no doubting their passion and enthusiasm. And on many a school day, the red apes’ idea to exterminate all humans did seem to have some merit. Wearing down the wood of your desk for years and years just to learn how to grow food for people, how to build roads for them . . . Human children were taught completely different and much more fascinating things at school—and they, just like the red apes, did everything for themselves! “Apes were created to serve humans!” Dad snapped when I complained. “Just think of how few apes are able to go to school in the first place. You’re lucky, you know.” If he was too tired to argue, he’d just sigh more conciliatorily: “I suppose whoever isn’t a red ape in youth has no heart, and whoever isn’t a blue ape in old age has no sense.”

In our house (and actually along our whole street), every activity that required proximity to humans was delegated to my father. It was the logical thing to do, as he had so much contact with them through work. First and foremost, it meant humans entrusted him with a lawn mower. Dad was tasked with its safekeeping, fueling, oil changes, and, of course, mowing lawns on our street. Multiple times a week, humans would take him to their neighborhoods to mow their yards as well. “In this world, there is no greater spiritual communion with humanity than mowing grass,” he said tenderly. “No other activity unites primate and human more.” When he returned, his vestments—a suit, white dress shirt, tie, and dress pants—smelled of sweat and fresh-cut grass, but he never took them off, even when mowing our own yard. Humans were impressed, as “ordinary apes” usually never wore clothes. Mom had to wash all those green-striped shirts, of course. I remember, when I was just a pipsqueak, I even told her that I never wanted to be reborn a human because it’d mean having to wear clothes all the time. Mom laughed and agreed.

Dad only undressed between the four walls of our home. I remember a recurring scene where, after a long day spent among people, he sat slumped in the armchair, snoring and hugging a big bottle of fermented juice, his clothes lying in a heap next to him. I saw it repeat frequently later, to be honest, and it seriously undermined my faith. I felt that to live like a human was too great a burden for an ape. Was there any hope of us becoming human? Was there even any point? Dad’s faith was never shaken, of course.

Several times, Undo and Redo said right to my face that my father was just after a medal: the Order of the Fellow Human, the highest honor that could be bestowed upon an ape back then, and perhaps still by the time you read this. Yet, I know that Dad had no such ambitions. True, he was awarded the Cross of Hominidae, Third Class, for his contributions to furthering cooperation between the human and ape churches, but he merely kept it in a drawer and never wore it in the company of other apes. And if so, then only at a formal human-organized reception. The fact remained that he was motivated solely by faith and duty. And he truly enjoyed being around humans, getting along with them wonderfully. It wasn’t uncommon for a human to pay us a visit—hairless and warm, surrounded by an intriguing scent. As a young chimp, I had the opportunity to sit on many a human lap. Such gatherings typically wound on till the early morning hours. The human would invite their acquaintances to join, Dad would call his own in turn and, in the end, everyone in that merry assemblage would do and say things that furthered our hopes that humans and apes might someday even inter-exist. Times were different, disorderly, and free: the red-ape regime had just been toppled and to be a human-friendly blue-ape was a novel and fascinating way of life.

My most vivid memories from that period revolve around Anders Metssalu, a brilliant young scientist renowned among humans and a frequent visitor during the restoration of the human state. My mother had granted him a brief interview and later, at our home, in an even more liberal environment, he showed an interest in her that was perhaps somewhat too animated for a person. I don’t know what she did or did not show the man, but in any case, he gradually became a good friend of my father as well. I remember them conversing in the kitchen while sipping mandarin-orange liqueur till late at night. I crouched behind the door and eavesdropped for a very, very long time, but only one breathtaking, outstandingly generous remark from that evening was seared into my memory: “A chimpanzee is 99% human.” I can’t say if Dad had any idea what the concept of percentage means, but no doubt Anders’s tone and expression at that moment conveyed everything a buzzed pastor of the Church of Manifestation needed to hear.

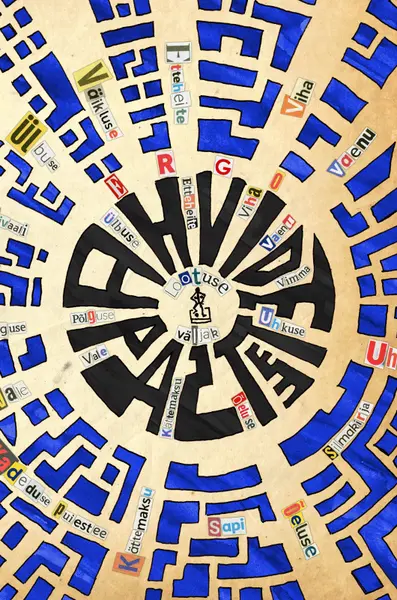

Tõnis Tootsen

Ahvide pasteet

Pâté of the Apes

Kaarnakivi Selts 2022, 266 pp.

ISBN 9789916966433