Martin Algus (b. 1973) is known foremost as an actor, dramatist, and screenwriter. He has authored award-winning plays for over a decade and written scripts for popular Estonian films and TV series, including the popular comedy programs Ühikarotid (Dorm Rats, 2010–2012), Ment (Cop, 2012–2013), and the long-running drama Padjaklubi (The Pillow Club, 2014–…) about the lives of four young women. Algus likewise authored the screenplays of the Estonian hit comedy films Klassikokkutulek 1, 2, and 3 (Class Reunion; 2016, 2018, 2019), which are essentially remakes of the Danish Klassefesten (2011, 2014, 2016).

It thereby came as somewhat of a surprise when Algus’s novel Midagi tõelist (Something Real) received the Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Award for Prose in 2018. I cannot overly exaggerate my own surprise, as I was also a member of the awards jury that year. Nevertheless, drama and prose tend to be divorced in Estonia, as Oliver Berg recently remarked in his video review of Estonian drama in 2019.[1] That being said, there are a handful of literary writers who collaborate with the theater and manage to stage some of their plays on occasion. Traffic in the opposite direction is very unusual, especially the leap from writing TV comedies to receiving a ‘serious’ literary award – in short, it stood out. The author’s surname, which means “beginning” in Estonian, naturally prompted journalists to dabble in wordplay with their reporting.

Algus’s trajectory does seem logical if one peers closer at his artistic biography. He has always been interested in social issues, and although such topics are handled with greater gravity in his plays, they’ve even surfaced to a certain degree in his television scripts. Out of his award-winning plays, Janu (Thirst, 2007) depicts the life of an alcoholic and his loved ones, Postmodernsed leibkonnad (Postmodern Households, 2009) addresses different family formations and their fracturing, Kontakt (Contact, 2010) looks at individuals encapsulated in solitude, and Väävelmagnooliad (Sulfur Magnolias, 2013) explores the life of a woman who finds herself dealing with an unexpected and unjust caretaking obligation. The playwright often adds “based on-” or “inspired by true events” on the title page. He has named Sarah Kane and Mark Ravenhill – big names in 1990s British in-yer-face theater, whose works he has also translated into Estonian – as two of his greatest inspirations and models.

In his plays, Algus experiments with different styles while maintaining a clear and consistent signature. He loves to use bold, thick strokes when prodding societal pressure points. Whenever detailing a seemingly dead-end situation, he usually directs attention towards the factors that led the characters to that given moment: to their memories, especially those from childhood. Often, a traumatic encounter shimmers in the person’s past – violence or harassment inflicted upon them as a child, or perhaps merely a lack of proper care. This also frequently gives rise to violence committed in the present; there tend to be violent impulses simmering within Algus’s characters, in any case. At the same time, his scenes can contain unexpected twists and resolutions. A violent episode is not an easily achieved culmination, for the most part, but just one step on the path towards it. Algus also brings different storylines together or interweaves them in unpredictable ways, which is perhaps facilitated by his screenwriting background. Family is seemingly one of his favorite topics, which comes as no surprise – the harmonious nuclear family is the stuff of happy fantasies, and is always the first to suffer whenever anything goes wrong.

This also broadly applies to Algus’s novel and play with the shared title Something Real. The story came first as a play, simultaneously trying out a new style for him: monologue (Algus modestly points out that this has, of course, already been practiced widely elsewhere in the world, such as by the playwright Conor McPherson). When Something Real became lost in the shuffle on several theater directors’ desks, it seemed only natural to start rewriting it into a novel. In the end, though, both projects picked up momentum – Algus’s book release and stage premiere took place on the same day.

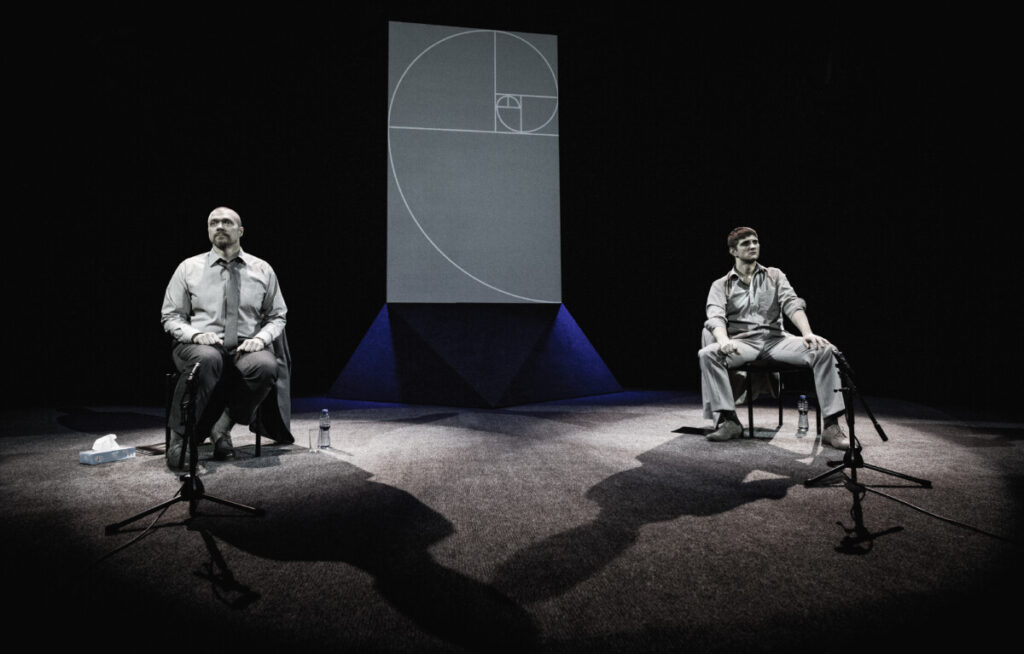

The play and the book are essentially identical, their main differences lying in the density of Algus’s writing on the phrase and sentence level, in accordance with their given genres. Two contrasting characters are juxtaposed, both middle-aged men with a ten-year difference: Leo works at an architectural bureau and lives with his wife in a terraced house in the suburbs; Carl has just gotten out of prison and moves in with an alcoholic woman named Leila. Leo analyzes and compulsively justifies his behaviors – he is articulate, constantly coming up with new arguments and counterarguments. The reader frequently has to wonder whether he is honestly debating his choices or simply rationalizing them to himself. Carl, on the other hand, speaks with a hint of local dialect, which in literary code generally points to a character’s lack of sophistication and presumably also their sincerity. He is surprisingly determined and gives the impression that he has everything under control, which later turns out to be false, of course. Despite the dissimilar manners of speech, the author inserts recurring phrases in the characters’ respective monologues, causing them to reflect each other. Both are searching for “something real”: for Leo, this entails breaking out of his truly oppressive middle-class pseudo-existence, while for Carl, it involves creating a picture-perfect family at long last.

Specifically, the plot of Something Real is knit around chatroom-enabled catfishing and blackmail. Longing to escape his suffocating secure lifestyle, Leo dives headfirst into the world of internet porn. Before long, he realizes he is addicted to a silly fantasy world and “something real” slowly manifests as the chance to meet a female internet acquaintance offline. Simultaneously, Carl methodically strives to construct a “real” family out of himself, Leila, and her two children; to keep them all on a straight path; and to improve their well-being. To do so, he believes he needs to first win their respect – to show them he has a plan. This leads to the inception of his idea to use 11-year-old Marta as bait for online pedophiles, then blackmail them. It is at this point where Leo’s and Carl’s paths cross. Although the former is in no way looking for young girls specifically (at least in his own mind), his attention is immediately caught by “Marta16” – a chatroom user who comes off as incredibly pure, melancholy, and real compared with all the others. And so it begins…

Algus’s story is packed with fast-paced developments, including a fair share of action scenes. There is excitement galore, especially for a relatively thin book. Even the common phrases that tie the dual protagonists together have perhaps a more powerful effect on the stage than in writing, where the actors volley their monologues back and forth. That being said, the use of dishonest narrators is a characteristic tool of prose, and with it, Algus manages to keep a question dangling throughout the work: who is normal, and what does normalcy even mean?

The twists and turns that the reader undergoes along with the two characters stem, in fact, more from the constant fluctuation of this assessment than from the doglegs of the plot itself. At first, Leo seems like a typical middle-class man with decadently perverse impulses that have started to raise their ugly heads while marinating in the monotony of “the good life”; Carl, on the other hand, is an honest small-time crook who actually wishes to live a decent life, but has been dealt a less-savory deck. These judgements are thrown into doubt relatively quickly. Leo’s behavior is obscene, but there is a human quality to it and, for the most part, he treats others with mild goodwill, holding no anger towards his unfaithful wife or the boss who fires him. Carl, however, is like a dog with a bone in regard to his gossamer dream, which increasingly reveals how blind he is to other perspectives and the tremendous degree to which he manipulates those around him. Nevertheless, these characterizations are not absolute: with Leo, for instance, Algus cleverly demonstrates how even an insightful self-analyst is prone to falling into the same old traps. That which is “real” is tenaciously elusive.

A thriller like Something Real truly deserves critics’ praise for its twists. No doubt Estonian readers will gradually accustom to it, too.

Johanna Ross (1985) is an editor of the Estonian philology journal Keel ja Kirjandus (Language and Literature). As a scholar, her main fields of interest include women’s and Soviet literature.

[1] O. Berg, “Kitsas tee püünele. Kodumaine näitekirjandus 2019”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z1Bcn6AcV4g&list=PLE_9_I6jBdE2T4kN9PijrTN_DfJEgyv6e&index=2&t=0s (accessed 5 July 2020)