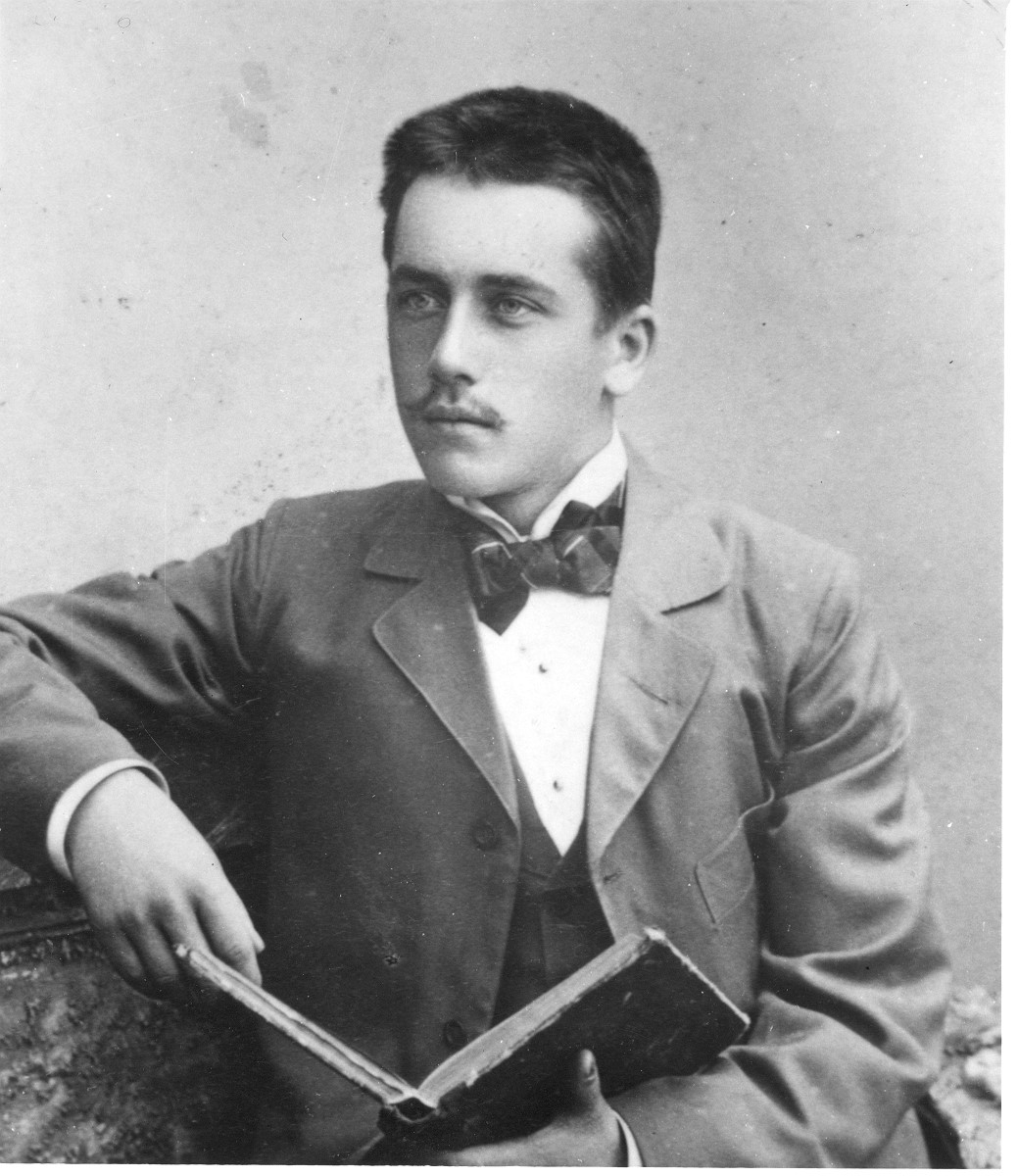

Born on 30 November 1883 in Võnnu, in southern Estonia, into the family of a village teacher, Suits came to Tartu in 1895 and began his studies at the then Alexander Gymnasium. The atmosphere of the old Estonian university town had an invigorating impact on the bright country boy whose expanding language skills enabled him to become more and more involved in world literature. This in turn made him think about the limited nature of his own culture and evoked a wish to do something himself.

At the tender age of 16 Suits published his first critical article in the newspaper Uus Aeg (New Time); a bit later the same paper published the young author’s first poem, Water Lilies (1899). These earliest efforts were nothing special – Suits was certainly no Wunderkind in poetry. The groundbreaking action in his life and work was establishing contacts with Finland and its culture. Beginning in 1901 he spent his summers working in Finland as a home tutor of German and French, and later studied for lengthy periods in Helsinki. In 1901 he also began his enthusiastic activities in ‘The Friends of Literature’, a circle of Tartu schoolchildren. They published three literary albums titled ‘Rays’ (1901-1902). After 1901, his poetic voice clearly began to develop.

The activities of the literary group Noor-Eesti (Young Estonia) between 1905-1916 were closely connected with Gustav Suits.

Noor-Eesti was probably the most influential literary group in Estonian cultural history. It grew out of the Tartu school circles, and its intellectual and ideological mentor was Suits. The year 1905 saw the publication of Young Estonia’s first album. In the lead article ‘Aspirations of the Young’, Suits expressed the main slogan of the movement: Let us be Estonians, but also become Europeans! 1908-1909 saw noticeable creative achievements. Young Estonia’s third album especially stood out for its novelty. Cultural historians have different opinions about the aspirations of the Young Estonians towards Europe. It has been claimed, on the one hand, that it was precisely Young Estonia which initiated a European epoch in Estonian literature, but on the other hand that they actually did not bring along anything new because already the great literary figures of the 19th century, e.g. Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald (1803-1882), author of the national epic Kalevipoeg, and the patriotic poet Lydia Koidula (1843-1886), not to mention the founder of the Estonian novel, Eduard Vilde (1865-1933), were influenced by European culture.

Earlier Estonian literature certainly displays traces of European literary traditions, although those were somewhat one-sided, due to historical circumstances largely relying on German literature. Young Estonia attempted to extend the field of influence primarily towards France, but also towards cultures of the Nordic countries. Equally significant was the fact that Young Estonia did not merely wish to learn about foreign cultures and use them to their own advantage, but they also wanted Estonia to reach the level of European culture of the time and to influence its development. From the culture of a backward small nation under the occupation of the Russian empire, this in fact demanded a gigantic leap, verging on the miraculous. Gustav Suits was fully aware of this seemingly hopeless situation when he asked in the lead article of Noor-Eesti’s first album: is such an elevation of Estonian literature and artistic standards at all possible, isn’t any advance from the present modest level totally excluded? And he replied with utmost optimism, forbidding the use of – in the words of the French writer Octave Mirabeau — such a stupid word as ‘impossible’…

The Young Estonians thus set about preparing for the great leap to Europe. The group’s nucleus also included the prose writer and critic Friedebert Tuglas, poet and literary scholar Villem Grünthal-Ridala, linguist and writer Johannes Aavik, critic Bernhard Linde and others. Many authors supported the goals of Young Estonia with their work, e.g. the later grandmaster of the novel, Anton Hansen Tammsaare, and Finnish-Estonian writer Aino Kallas. ‘Experiment Europe’ was successful – surprisingly so – but it naturally involved only a part of Estonian literature of that period, evoking fervent opposition among conservative nationalists, but also among critical realists. Young Estonia was accused of being alien, imitating French and other nations’ literature, of elitism and of a disregard for Estonian readers. In hindsight, quite a bit of this criticism seems true, but the steps taken by Young Estonia were nevertheless fundamental in the development of Estonian literature.

Young Estonia’s innovations mostly occurred in poetry, short prose, and literary criticism. In poetry, Gustav Suits clearly held sway. During the active period of Young Estonia, Suits was living in Helsinki. Between 1905 and 1910 he read European literature, Aesthetics and Finnish language, literature and folklore at Helsinki University. After graduation, the young writer and literary scholar could not find a job in Estonia and stayed in Finland for years, working in the Helsinki University library and then as a language teacher in a gymnasium. During his Finnish period, Suits naturally spent some time in Estonia. After busying himself in the Young Estonia movement, he participated in the emerging Estonian political life in the revolutionary year 1917, in the party of socialists-revolutionaries. Like many members of Young Estonia, Suits was politically left-wing, although he did not share communist or Soviet opinions. In 1911 he married his fellow student in Finland, Aino Thauvón, with whom he had two daughters.

After Estonia became independent, Suits was invited to take up the position of Professor at the University of Tartu, which had gained the status of a national university. He arrived in 1921 and stayed until 1944. Suits was the first professor of literature to teach in Estonian at the university level, and his work as a scholar and university professor was groundbreaking. He delivered lectures in literary theory, comparative literature and Estonian literary history – the latter was his main area of study. Professor Suits primarily published research papers on older Estonian literature, particularly on Kreutzwald and his time. On Suits’s initiative, the Academic Literary Society was founded in 1924 at Tartu University, organising lectures and meetings and issuing its own publications. Highly valuing contacts with Europe, Suits frequently travelled in Finland, France, Germany, Holland, Sweden and in 1939 also in the Soviet Union. He delivered lectures at the Universities of Königsberg, Stockholm, Göteborg and Lund, was elected a corresponding member of the Finnish Literary Society and the French Academy, and was awarded an honorary doctorate by Uppsala University. Throughout the period when Suits was working at the university, he was almost totally silent as a poet. He was, however, a sharp critic and publicist.

The fateful years of the Second World War brought Suits, first of all, the loss of his home in 1941 – his house in Tartu burned down, together with his huge library, archives and manuscripts. Numerous unpublished scholarly papers perished. In 1944, before the arrival of the Soviet troops and the new Soviet occupation, Suits, like approximately 70 000 others, fled to political exile. The Suits family travelled via Finland to Sweden. The last stage of the poet’s life was spent in Stockholm, where he was amazingly prolific in research work and wrote poems as well. In 1953 he fell seriously ill and died. He was buried in the Stockholm Forest Cemetery.

The poetry of Gustav Suits is meaningful in various senses. It is an expression of an educated thinker and a poet possessing an original talent, and at the same time characterised the aesthetic principles of the Young Estonia movement and the general line of development during the first decades of the 20th century. Suits’s poetic oeuvre is not extensive: he published six collections of poetry, but almost all of them are landmarks in Estonian literature. Typically of high-level literature, Gustav Suits’s poetry combines both the very personal and general. It depicts the history of his land and people and reaches out to touch the fate of humanity in general.

His first collection, The Fire of Life (Elu tuli, 1905) is the simplest of all his poetry books, the most popular, reader-friendly and appealing, due to its youthful enthusiasm. It was a kind of preparation for the readers of that time for more demanding lyrical works. The manner of the young poet betrays the influences of Friedrich Nietzsche and the Finnish poet Eino Leino, but it also reveals traces of 19th century Estonian national romanticism. His attempt to join national ideas and the new, self-centred, individual world outlook in Elu tuli does not always produce a convincing artistic result, but the poet’s spirit of a determined seeker cannot leave anyone indifferent. This collection of poetry gained wide response partly due to its connection with its time: Suits’s poems reflected the rising mood of Estonian society in the early 20th century and the revolutionary atmosphere of 1905, expressed especially in its declaration of the younger generation’s great hopes and high ideals. The title poem, The Fire of Life, as well as The End and the Beginning, Men, Young Blacksmiths and others, display a surprisingly plucky spirit. At the same time they possess a personal shading of emotion and are poetically elaborate, bearing no resemblance to the typical verse slogans of so-called working class poetry.

The mood of The Fire of Life, however, is not just militant. It also contains memorable love poems, born out of an enormous sense of happiness. The muse in this case is a girl of Swedish-German origin whom Suits met in Finland. She was known as the Spring Girl. The relationship between Suits and the Spring Girl was truly romantic, but their background and world views drove them apart. The story of Gustav Suits and his Spring Girl and their correspondence was later presented in a fascinating book by the poet’s wife, Aino Thauvón-Suits The Youth of Gustav Suits (1964). In any case, The Fire of Life contains passionate and – considering the conventions of that time – even remarkably sensuous poems inspired by happy love, such as Young Love, Time of Youth, Spring and Autumn, etc. The well-known An Island of My Own, which later acquired a more general meaning, first appeared in the cycle of love poems dedicated to the Spring Girl. The second collection of poetry, The Land of Winds (Tuulemaa, 1913) is to a large extent a total contrast to The Fire of Life, primarily in terms of its attitude to life and prevailing moods. Historically, it reflects the post-revolution mood of decline, the disappointment of the poet and his generation, and a sense of premature ageing. One poem bears the title The Old Young. The poems abound in allusions to matters Estonian; the most vivid example here being Song About Estonia. Its grimness and pain resemble the work of Juhan Liiv (1864-1913), our greatest patriotic poet. The personal feeling of Suits as someone living away from his native land is also strongly felt. It can be said as well that The Land of Winds expresses something universally human or typical of 20th century man: doubts, disappointment in rationalism, feelings of insecurity. The wish to find a place of one’s own in the windy world – or to create one’s own Land of Winds — nevertheless persists. Contemporary, as well as later, reviewers have paid great attention to the meaning of the image of the Land of Winds. Is this Estonia, suffering in the winds of time, or the refuge of the poet’s own mind and spirit? The symbolist image allows both interpretations, being simultaneously a general vision of the whole world and life as an unpredictable and forever changing domain of winds. The only choice is to accept this volatility which, for a man who has distanced himself from nature and traditions, means finding the lost unity again. The poem Under the Trembling Aspens displays the most vivid recognition of the initial togetherness of man-nature-creative work-cosmos.

The Land of the Winds is considered one of the most masterful collections of poetry in Estonian literature. It is truly stylish, precise in form, closest to French literature (Gautier, Baudelaire, Verlaine) and Russian symbolism. Its form is diverse, almost like an anthology where the poems range from demanding classical terza rima to fragile free verse. Still, classical and traditional verses prevail. The images, squeezed into strict stanzas, are tightened to the extreme and are full of tension, so that the form threatens to crack or burst at any moment, as for example in the four-part cycle The Land of Winds I-IV.

This kind of cracking or deliberate breaking of the form can be observed in the 1922 collection It Is All but a Dream – a collection entirely new and different from both The Fire of Life and The Land of Winds. Admittedly, there are occasionally more complicated phrases and lines of thought that require some effort on the reader’s part also in The Land of Winds. It is All is but a Dream, however, was written in a much more modernist and intellectual vein. It includes, for example, the excellent free-verse poem A Voyage Home, depicting Suits’s journey from France to Finland, crossing the dangerous North Sea of the First World War. The visions presented intertwine places and times- the melee of war refugees on the ship, recollections of visited cities, thoughts about Europe’s past, present and future. Poetic imagery is joined with prosaic expressions. The poem’s modernist technique resulted in its being seen as innovative throughout Europe.

The collection of poetry itself is highly diverse and contains poems written over a long period of time, which together form a kind of diary reflecting radical events in history, from the beginning of World War I through the 1917 Russian revolution to Estonian independence. The poet also casts a critical eye on the social contradictions of the newly independent Estonia, its dishonesty and snobbery. The poems Balladeer of the Time, Changing Flags and Old Devil are among the most original achievements in Estonian expressionist poetry.

The Land of Winds, in particular, but also All is but a Dream and The Fire of Life, established Suits’s fundamental position in Estonian poetry. Suits, however, has other surprising works. The longer ballad, Birth of a Child (1922) is an impressive literary work, an imitation of old Estonian folk songs. It successfully unites the ancient and modern world views. The collection Fire and Wind (1950), published in Sweden after a long ‘poetic pause’, excels among earlier Estonian exile poetry. Gustav Suits, as a poet, deserves admiration primarily because of his uncompromising soul, which keeps searching. Even in his first collection of poetry he had found a style that served him nicely for a long time. Suits, however, never stopped at whatever had brought him recognition. Each of his books was a new attempt to test the possibilities and boundaries of poetry. Suits never sought popularity or tried to please the readers of his time. Partly because of this, his work has fascinated and still fascinates new generations of readers. Suits’s poetry has had a strong impact on the best and most original Estonian poets, including Henrik Visnapuu, Marie Under, Heiti Talvik, Betti Alver, Bernard Kangro, Paul-Eerik Rummo and Juhan Viiding.

© ELM no 16, spring 2003