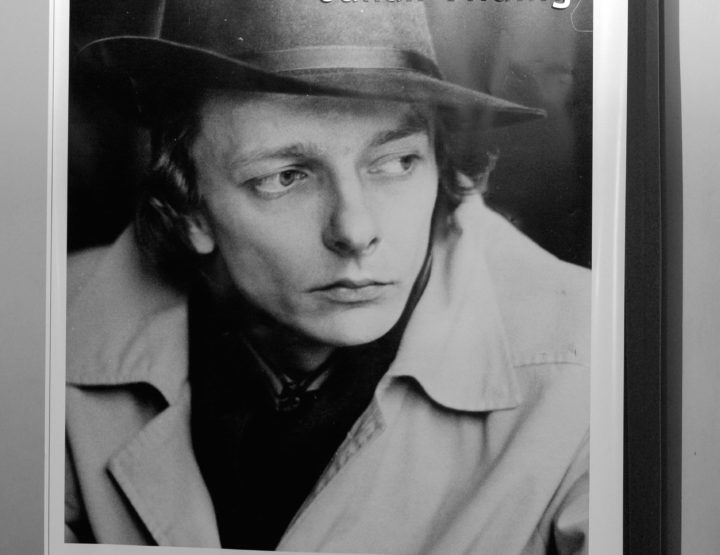

Tõnis Vilu is one of the most outstanding and significant Estonian poets today. He has published eight[1] works in less than a decade, each remarkably distinct from the last. As fellow poet Hasso Krull wrote: “In a very short span of time, Vilu has brought more tonality to Estonian poetry than Krull, Kivisildnik, and Kesküla combined in the early 1990s.” Referring to a remarkable transformation that shook the former truths and methods of Estonian poetry to the core, the remark is particularly meaningful.

Aside from Vilu, I doubt you could find a single Estonian author who has released eight high-quality but poetically unique works in such quick succession. The aim of this overview will be to highlight his different styles: I will briefly describe his earlier collections but dedicate more attention to his latest, which are substantial to yours truly.

With the debut collection Oh seda päikest (Oh That Sun, 2013) and its lyrical poems on environmental topics, Vilu proved himself to be one of the most linguistically sensitive authors in contemporary Estonian poetry. His works are dense and edgy, and written with sensitivity. The language is treated with intimacy and intensity: Vilu bickers with it, shakes it and bends it to achieve a unique kind of simplicity. Since his debut, Vilu’s poems have been very compact; interweaving voices and a variety of levels and topics. Nevertheless, he manages to preserve accessibility, temporal transcendence, and a universal force. It appears that the author’s poetry is becoming increasingly personal with every new book, though it is still conscious of theoretical, philosophical, social, and political issues. This is no doubt why Vilu earned the attention of critics and literary researchers early on.

Beginning with his second book Ilma (Without, 2014), each of Vilu’s collections have been conceptual wholes and yielded to the “serial principle”, in which the interaction between and development of individual poems is particularly important. The layers of meaning in one piece are often revealed in harmony with others and/or through the micro- or macro-narratives throughout the work. In an interview, Vilu put it this way:

“Different poems that are nevertheless strongly connected give a much more polyphonic image of the subject, creating a network of symbols like in a novel. I also enjoy the intermediacy or multiple levels that are created when a poem works both alone and in concert with others, and in various ways at that.”

Vilu’s symmetrically structured collection Without has been called fantasy poetry. In the third-person, it is the journey of a wanderer through a desolate, frozen landscape conveyed in couplets. Literary expert Jaak Tomber has defined it as a suspended post-apocalyptic moment that allegorically reveals several burning core questions, which are present in all of Vilu’s works. These include, for example, the ego and/as nature, the environmental crisis, the ego and loneliness, adjustment, and adaptation. To be fair, all of Vilu’s books contain social critique to some degree or another, probing the subject’s difficulty adapting to the opaque contemporary cultural space.

The pervading theme of Without is created by recurrent elements and motifs, a fictitious universe, and a wanderer. Vilu’s next collection, Igavene kevad (Eternal Spring, 2015), is an epic lyrical work that continues in an unreal register. It features main and secondary characters, a clear motif, and a fictional world that is similarly frozen – both living beings and nature as a whole are stuck somewhere, unmoving. We can only ask ourselves how to move forward, change, transform, and breathe in the stagnation. Whereas the earlier work was composed of two-line strophes, the sensually intense Eternal Spring is constructed of fourteen-line free-verse sonnets and divided into three lengthy sections rooted in different voices. The latter aspect makes the collection particularly fascinating, and is practiced more in his later works. Narrating the first section is a female anthropologist who has found herself in a tiny off-limits village. The second and third sections are populated by a third-person male instructor and a male artist, respectively. A further twist takes place when the narration returns to the first person in a description of the artist’s dream, prompting the reader to reevaluate the whole earlier fiction in retrospect.

In Vilu’s digital collection Uus Eesti aed (A New Estonian Garden, 2015), he scrutinizes the topic of mental health more thoroughly than any other Estonian poet to date (this grows increasingly complicated in his later books and interweaves with several other topics). As the author himself has commented, it describes “a mental state that softly desires, and is slipping into, escapism.” The monologue section “Before” comprises school-day memories mixed with present, topical musings. He expresses anxiety, a wish to escape the world, and anger towards the past and present inescapabilities. Essentially, A New Estonian Garden is also divided into three parts: the first is one of angst, the second of revenge-driven conflict, and the third drifts from the first-person to multiple perspectives; projecting a modern-day utopia conveyed by the making of a new metaphorical garden. The “I” perspective shifts into the “we” of romance, a condition of the new garden’s existence. Now, everything is clear; now, peace is made with the present, the past, neighbors, and oneself. It is the emergence of Vilu’s “positive agenda”. Although desolation and twilight radiate from Vilu’s earlier writing, he proves that he believes in empathy and love.

Mental-health topics take center stage in Vilu’s subsequent works and with it, he shifts from an elliptical style to something closer to prose. While A New Estonian Garden ends with the lines: “darling tell me / I haven’t gone crazy”, his Kink psühholoogile (A Gift to the Psychiatrist, 2016) focuses on a specific mental disorder: bipolar disorder. The epic autobiographical confession in poetic form has been called “documentary poetry”, an “illness poem”, and a “confession of one’s clinical state”. True enough, the divide between the narrator and the author is razor thin. The book is also exceptionally physical in nature, which is given away by its cover design: the author photographed in water, his eyes concealed by dark swimming goggles and his lips painted cherry-red. Vilu’s narrative is interspersed by more elliptical, rap-like, rhythmical, emotional, and sometimes even enraged poems (“revolutionary songs”), which are set on enlarged sections of the Roy-Lichtenstein-like cover photo. The blurb on the back cover reads:

“Life as a bipolar person is one big bout of anxiety, even when the meds are already working. The doctor told me I’ll be taking the pills till the end of my life because, at some point, years from now, something bad might happen again; maybe even several times. So, all I can do is wait for the misfortune, trying to guess when it will arrive.”

Yet, the writing itself isn’t borne of this waiting: the narrator alternates cautiously between what happened earlier, how things were before the illness was under control, what life was like when he started medication, and how things are now. Retrospective accounts add depth to the narrative, as do musings over what life and relationships were like before and after receiving treatment, and what will come next: “What will become of my kid? What is this powder bubbling within me doing to them? What will they be like when they’re born?”

Vilu has written several blog posts about being bipolar and has discussed it during performances. The poetically-charged description of his medical condition is exceptionally rational, including digressions over the nature of the illness and many technical terms that raise broader questions: Who am I? What is this split within me? How are ego and body connected? How can I accept myself, reassemble my pieces, feel whole again, and distance from myself?

As literary expert Aarne Pilv put it: “The question is whether or not I am free to talk about myself; whether I am capable of freely conditioning myself; whether I am free to speak about myself as someone else or a third person.”

Conflict with the psychiatrist leads to the question of reality and fiction; of the existence of illness as such. Specifically, the psychiatrist discovers that the narrator is a poet and is dissatisfied with how they are portrayed:

“No, no – it’s just fiction, just literature, I caricaturized you, / extrapolated you and…” / “Nobody extricates me.” / “That’s too bad. What I mean to say is there’s definitely some truth to it, but / you can’t take it all so seriously. The other characters in it are / pretty much idiots, too.” / “I see. / But you write rather, well… frankly. Does it mean you / believe your illness isn’t real, either?” / “No, no, though… well, it’s hard to say. I’m not the expert here. / The pain is real! Dark depression, memory gaps, / recovery – it’s all real!”

A Gift to the Psychiatrist gradually moves from the personal level to become more political and critical of society. Vilu’s depression-themed Libavere (Shifting Blood, 2018) consistently ties mental brokenness to various levels of society. The work is visually jarring, the author seeming to incessantly bite his own tongue. Its poems are incorrectly constructed from a linguistic perspective, brimming with grammatical and phonetic “disorders”.

The language of Shifting Blood is chock full of meaning, its flawed nature complementing the narrator’s psychological “defectiveness”. At the same time, this doesn’t inhibit reading comprehension. The various layers are mutually motivating: the narrator has difficulties expressing himself, which makes him feel self-conscious and causes low self-esteem and depression. This sense of brokenness is revealed in Vilu’s language itself: a faulty vehicle prevents him from expressing himself and others from understanding him, which only debilitates him further. Or vice-versa: since the narrator is broken within and cannot express himself, the language is broken as a result. It is tangible when we read the text’s errors and grammatical mistakes; you can tell that something is very wrong. A broader macro-narrative forms through the burgeoning disturbances and relatively accessible New Sincerity and once again climaxes with “WE”; with love. The narrator can’t fathom how someone like him can share in a utopic structure the likes of love (“WE”), but in the end, love brings everything together. It is, as they say, believed in.

The impact of Shifting Blood also lies in the way that various layers of upside-down lust are constantly, almost effortlessly, reconciled; in how the phonetic and grammatical mistakes are mentally “fixed”. This leads, in turn, to a theoretical conflict that Jaak Tomberg and I have defined as such:

“In order to reach the thematic dimension, we need to automatically eliminate the crux of what Shifting Blood constructs; to put parentheses around the errors; to push the errors onto a latent level. Only then can we clearly observe the narrator looking at himself from an outside perspective; wondering what people think of him; defining himself negatively; as well as how he points to the sub-language, now under narcosis, and legitimizes it.”

It is by implementing these mistakes, with the help of hampered pronunciation, that the reader is immediately set on a meaningful, world-constructing dimension. The fact that one has difficulties reading the text aloud or in their heads means that they physically experience the full inability to express and to exist.

Tundekasvatus (Sentimental Education), which received the 2020 Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Award for Poetry, is also a finely arranged collection that touches upon recent uncomfortable political topics and places them in the most intimate of registers. It is poetry that pinpoints one social perspective during a precise moment in time, along with all the fantasies and tensions that accompany it.

On the most basic level, Vilu ties together two reflecting and interweaving narratives, which trace a Bildung and supersede every individual poem: a painful life in the narrator’s homeland and a counterfactual life in Japan. The opening poem serves as the collection’s clef (looking back at one’s homeland from abroad, memory, collecting memories, etc.) and is gradually developed until the final piece ties together all the different ends/dimensions and many of the topics.

Whereas personal brokenness was most apparent on the grammatical/phonetic dimension in Shifting Blood, thus giving it strong potential for physical sensation, Sentimental Education’s brokenness is revealed through multiple dimensions, most strikingly on the similarly broken social/political level. The narrator’s inner crisis is compared to social processes from a generational standpoint, including topics like environmental catastrophe and social governance (and even high- and late capitalism). The interweaving of layers of meaning allows Vilu’s dozens of different themes to gradually develop, transform, and renew. An array of alternating voices and constant appeals constructs the narrator’s broken persona. Previously, I’ve called Sentimental Education a kind of alphabet book of poetry that uses hundreds of different styles – from ample intertextuality to parallelism.

Sentimental Education is also exceptionally sensitive in terms of language, containing several different linguistic dimensions (colloquial, journalistic, and many other specialized styles) without producing cacophony. Vilu’s use of language is so flexible that even completely improbable pairs start to seem natural. Simultaneously and with the utmost fluidity, he switches between themes, narratives, dimensions, and focus at a dizzying pace, doing so primarily through language (both on the surface and thematically). A single line might include the narrator’s psychological brokenness, scathing criticism of politicians, a statement addressed to the sun, a declaration of love, and more. Still, every element is interconnected in the only way possible.

Vilu’s latest poetry collection Kõik linnud valgusele (All Birds to the Light, 2022) turns to a traumatic early memory: it is addressed to a childhood friend who committed suicide. Taking the place of broader social/political statements, multiple voices, and changing linguistic registers are painful flashes of memory, tiny sensations, and individual moments. Childhood landscapes and scents, memories of playing with friends, mundane details – all remind him of a friend he was unable to help. It is a powerfully lyrical book where intense descriptions of nature blend with the narrator’s mental universe; where the outer, inner, past, and present become indistinguishable from one another. Thus, statements made to the lyrical “you” are always statements made to oneself. The line between the narrator and his late friend grows hazy:

warm late-evening rain moist soil a smell emanates from the window

outside rest a little from the burying now my late friend let

it rain I lie in the ventilation window and am a ventilation window cover myself

the extinguishing dripping lampshade has had enough

All Birds to the Light is also a structurally homogenous work – Vilu’s transition-rich poems are visibly similar as well. Still, you can also sense him walking the paths of his debut: the new collection has a definite narrator, an intense relationship with nature, and harmony between the inner- and outer worlds. Although Vilu’s poetry books are entirely dissimilar, his writing is held together by a common worldview and sense of life: by a sentimental education, probing the deeper nature of humanity, and an intimate relationship to language. By belief in empathy and love. By knowing that “I am nature, too,” to use Vilu’s own words.

Joosep Susi (b. 1989 ) is an Estonian journalist, literary expert, instructor, and philosopher.

[1] Eight works isn’t entirely accurate, as only seven have been physically published; Uus Eesti aed (A New Estonian Garden) was released digitally. One could also count his online poem “Thoughts Like Torn White Rags” (2013), which I will not address in this piece.