Jaan Kross first came to prominence in the English-speaking world in 1992 with the publication of The Czar’s Madman (Keisri Hull), translated by Anselm Hollo. A grimly absorbing novel about the folly of political idealism, the novel concerns the alleged insanity of a Baltic-German aristocratic, Timotheus von Bock, who was stationed in 1820s Livonia (present-day Estonia and Latvia). Baron von Bock has the temerity to send Tsar Alexander I of Russia a list of proposals for constitutional reform and moreover upbraids him for his maltreatment of serfs. His criticisms land him in jail for eight years.

Upon its publication in Soviet Tallinn in 1978, Keisri Hull sold an impressive 32,000 copies. Kross’s paradox – is von Bock mad, or does his truth-telling illuminate the “insane” world in which he lives? – anticipated the Brezhnevian psychiatric asylums and the misuse of medical diagnoses in the USSR to silence dissidents. The émigré Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky (who shot parts of Stalker in Tallinn) reportedly wanted to film the novel, but died before the project could materialize. Forty years on, The Czar’s Madman endures as a European masterwork; it has the pleasurable density of a 19th century novel and moreover radiates a pleasingly old-fashioned gravitas.

Kross’s early years unfolded happily in pre-Soviet Tallinn, where genteel standards prevailed. His father was a machine-tool foreman and reasonably well-off. As a boy, Jaan attended the local Jakob Westholm Grammar School and from 1938 he studied law at Tartu University. At Tartu, he met Helga Pedussaar, a philology student and, later, translator, whom he married in 1944. On the eve of World War II, Kross was made an assistant university lecturer in international law, but all was not well. Rumours of Stalin’s Great Terror had begun to reach the campus: Estonia, on the edge of the Slav world, was in imminent danger of Soviet takeover. In June 1940, after two decades of independence, Estonia succumbed to Soviet occupation. Some 9,700 Estonian army officers, clerks and priests were deported to collective farms in eastern Russia, if not executed. Not surprisingly the deportations had a nightmare quality for Kross: the last novel by him to be published in the UK before his death, Treading Air (2003; originally issued as Paigallend in 1998), was a semi-autobiographical account of Estonia’s wartime devastation and humiliation, where Stalin’s departure was followed by further brutality under occupying Germans.

Kross was able to avoid conscription into the Waffen-SS Estonian Legion by swallowing pills that produced thyroid gland swelling. On the morning of his medical check-up he chased down the pills with a measure of brandy and became dangerously bold and loquacious. “The German medical officer examining me said I was a drunken idiot not worthy of fighting and struck me off the conscription list”, Kross told me in an interview for the Guardian in 2002. At 82, Kross was frail and had recently suffered a stroke. He was living, I remember, with the poet, children’s writer and translator (from Hungarian) Ellen Niit, his third wife, in an apartment in the Soviet-era Writers House in central Tallinn. In the course of the interview, Kross had the modesty of the true writer, and a sorrowful yet at times slightly mischievous presence. He said he was “itching” to write another novel but was content for the moment to work on his memoirs, which were published as Kallid kaasteelised (Dear Co-Travellers) in two volumes in 2003 and 2008.

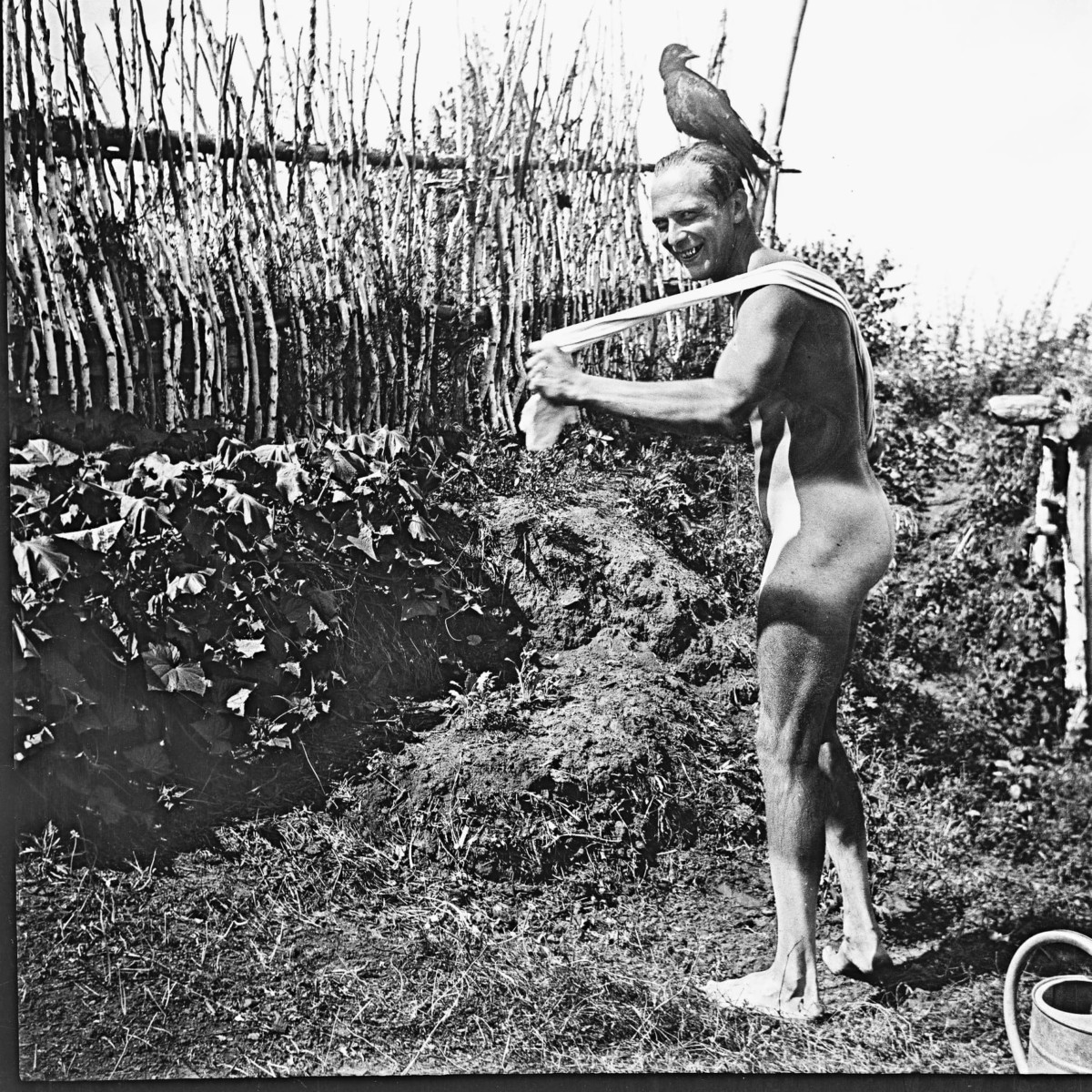

Photo by Peeter Langovits / Scanpix

Kross continued to teach international law at Tartu University during the second Soviet occupation, only to be arrested in January 1946 by the KGB. He was taken to the KGB headquarters on Tallinn’s Pagari Street and placed in a cell there with four other men condemned to death. The 26-year-old Kross had never actively resisted Soviet rule yet suddenly he was a “bourgeois recidivist”. (It did not help that his father had been deported in 1945 to the Mordva Autonomous Republic, where he died). Although reprieved from execution, Kross spent the next eight years in the Gulag, a fate shared by some 150,000 of his compatriots. He slaved in a coalmine near the feared Vorkuta camp west of the Urals, and later at a brickworks in the Krasnoyarsk region. Conditions were appalling but Kross had the good fortune, in 1949, to work as a felt-boot dryer, thus avoiding the sub-zero temperatures outside. Bizarrely, two of his co-prisoners were English: one was a Communist accused of anti-Soviet espionage, the other a former Wehrmacht conscript. (“They argued the whole time so I was unable to practice much English with them”, Kross told me.) While in the Gulag, Kross met and married his second wife, Helga Roos, an Estonian translator of English and German. With the Khrushchev so-called “thaw”, he was allowed to return to Tallinn with Helga in 1954. There he began to translate a selection of the classics, among them Shakespeare, Balzac and Lewis Caroll. (“Soviet patronage of the arts, though it could be repressive, nevertheless ensured that some of the great European works appeared in Estonian”, Kross told me.)

His first volume of poetry, Söerikastaja (The Coal Enricher), came out in 1958; the erudite, allegorical-ironical free-verse introduced unusual themes of galaxies, electrons, Milton, Homer (and of course sputniks). Nevertheless it was denounced by the Soviet Estonian cultural monthly Sirp ja Vasar (“Hammer and Sickle”, today just “Sickle”) as “decadent” and “insufficiently Bolshevik”. Though Stalin had been dead for five years, Stalinist strictures still determined Soviet arts and letters. It was Ellen Niit (whom Kross married in 1958) who encouraged Kross to turn his attention to the historical novel: history at least would allow him to write obliquely of the Soviet present. In 1970, Kross published the first in a series of semi-factual historical works which made him famous, first throughout the Soviet Baltics, and later in the West. Neli monoloogi Pha Jri asjus (Four Monologues on St George) investigated the life of the Estonian artist Michel Sittow (1469-1525), who had worked as court painter to Queen Isabella of Spain. The breakthrough, though, came between 1970 and 1980, when Kross released his three-part novel on the life of 16th century Tallinn city elder Balthasar Russow, Between Three Plagues. Written partly to outwit Soviet censorship, and to chart the vagaries of Baltic life under foreign dominations, the trilogy remains a masterpiece of paradox and ambiguity.

The trilogy’s first two volumes, The Ropewalker and A People Without a Past, published in English translation by Merike Lepasaar Beecher in 2017, are brocaded with flavoursome period detail. Russow, born to a drayman in the poor Tallinn district of Kalamaja in 1536, wears a dog-skin cap and drinks quantities of malmsey wine from “juniper-fragrant kegs”. Plates of roast goose, salted pork, smoked venison and marzipan puddings are washed down with goblets of white klarett and Rhenish red. The smell of Russow’s Baltic childhood – paraffin, wet wool – practically lifts off the page. However, only in the loosest sense can Kross be described as an historical novelist. The Russow trilogy explores such contentious issues as nationhood, cultural assimilation and political exile. Russow is celebrated today in the Baltic States for his Low German-language chronicles of Livonia, first printed in Rostock, Mecklenburg in 1578. To Kross’s evident approval, Russow was highly critical of Livonia’s upper-class German rulers, who looked down on the Baltic peoples as a semi-pagan peasantry, good only for forced labour.

Estonians who managed to escape serfdom, such as Russow, could only do so if they spoke German, or Low German, a language considered at that time second only to ancient Greek. Russow’s rise from “peasant stock” to become Estonia’s first historian and the pastor of the Holy Spirit Church in Tallinn (a post he held from 1566 until his death in 1600) was extraordinary in the highest degree, though perhaps not without historical parallel. Three centuries later, Kross reminded me, one of Tallinn’s military commanders under the Tsars was a freed African slave, Abram Gannibal. The Cameroon-born Gannibal was appointed to the position in 1742 by Peter the Great’s daughter Elizabeth, Empress of Russia. Gannibal was the maternal grandfather of Alexander Pushkin. Kross had long wanted to write Gannibal’s story; but, it seems, he decided instead to chronicle Russow’s.

In all sixteen of his novels, Kross used history as a source of inspiration, as well as a way to restore Estonian national memory under dictatorship and confirm the country’s place as Europe’s ultimate borderland and microcosm of Teuton-Slav antagonisms. In 1991 he was given advanced warning that he would win the Nobel Prize in Literature and told to stay by the telephone. “It was easy to do, as I never really leave my flat, let alone leave Tallinn”, Kross told me. Nadine Gordimer won that year. Kross never did. That same year, after the collapse of Soviet communism, Kross returned to politics and took his place in the Estonian parliament, where he helped to draft the new constitution. Kross’s one-year stint as a Member of Parliament in 1991, chronicled in Volume Two of his memoirs, was in many ways extraordinary: at 72, Kross was by a long chalk the oldest member on the benches.

His discovery by English-speaking readers, long overdue, was of course only made possible by the departure of the Soviet censors. His later short stories, collected in English in 1995 under the title The Conspiracy,recount attempts by Estonians to flee to Finland during the German occupation and their later deportation by the Soviets. There is surprisingly little bleakness in his prison stories. Kross wrote about his incarceration under the Soviets with a poignancy devoid of anger. He died in Tallinn in 2007, at the age of eighty-seven. The third and final part of the Russow chronicle, A Book of Falsehoods, is due out in the UK in October 2019. I shall look forward to reading it.

Ian Thomson is the author of two prize-winning works of reportage, Bonjour Blanc: A Journey Through Haiti and The Dead Yard: Tales of Modern Jamaica. His biography of Primo Levi is regarded as a classic, while his book Dante’s Divine Comedy: A Journey Without End was published in 2018.