The year 2019 looms large in Estonia’s cultural calendar, marking the 150th anniversary of the Estonian Song and Dance Celebration. Its importance, however, does not merely lie in celebrating our song and dance tradition or commemorating our great composers and conductors of the past. It is also an occasion to pay tribute to our great poets whose work has often been the basis of the festival’s songs and who have, perhaps more than anyone else, borne witness to the nation’s spirit of persistence or been instrumental to it themselves. It might be difficult to grasp, for those devoid of the experience, but the fact is that for many Estonian people, a single line of a poem or song was often that last vital thread of consolation that kept them going in years and decades of hardship.

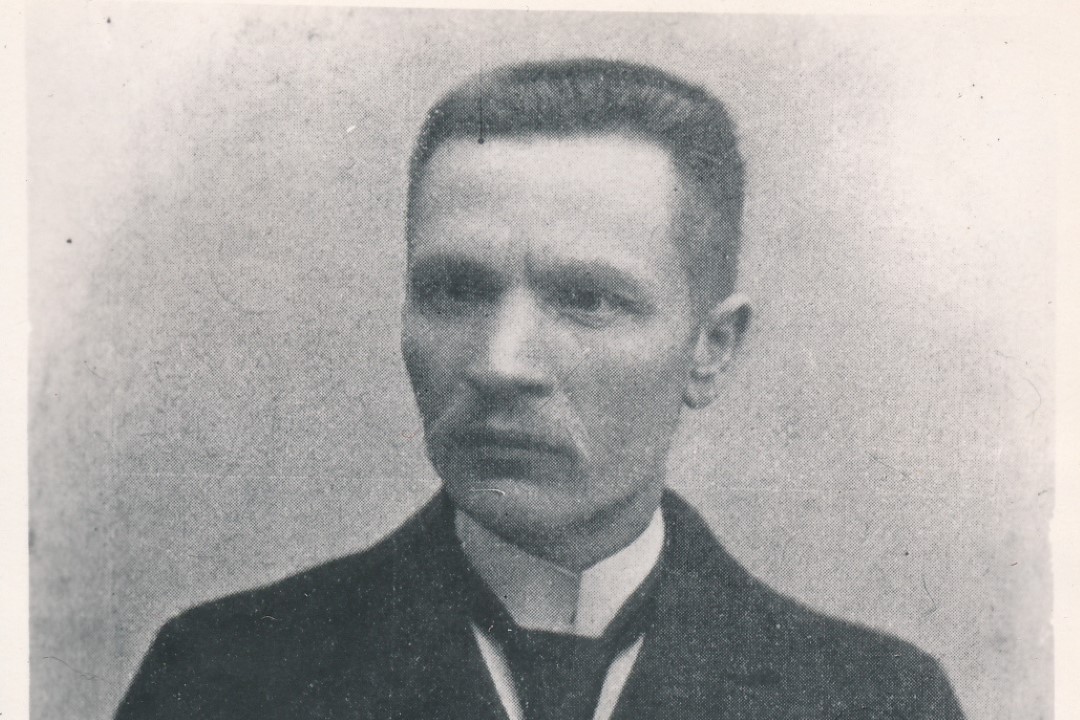

There is hardly another poet as evocative and influential in Estonian literature as Juhan Liiv. Almost every Estonian knows at least a bit of his poetry by heart and something of his life story. Traces of his ethos and style can be found in countless literary works that followed. And yet his importance is not merely literary. He is precisely one of those authors whose words have been the mentioned as threads of consolation and hope, one of those whose writing has found expression both through choral and popular music and played an important role there. It is in fact fair to say that part of Liiv’s work has nearly reached the status of folklore and people might sometimes cite it without even realizing the quotation’s origin.

More importantly though, Liiv managed to give a voice to a previously undefined, yet underlying element of the Estonian psyche and it is particularly in that capacity that his poems have steeped themselves into Estonians’ perception of their own national self. We recognize ourselves in his words and at the same time identify ourselves through the words that he has given us. There are very few poets in our literary legacy that share that status with him.

And yet Juhan Liiv was not at all an author famous in his lifetime. Born on April 30, 1864, in the village of Alatskivi on the eastern side of Estonia, he showed an early interest in literature, much by the influence of his older brother who was a writer and school teacher. Liiv’s own education remained unfinished though, for he had hard time acclimatizing himself to the rules and discipline of educational institutions. He later took up work as a journalist with various local papers and that allowed for the first publications of his own writing. Soon though, at the age of 29, he was diagnosed with mental instability and later with schizophrenia, which resulted in his long withdrawal from the public eye. Due to his seclusion over these years, some thought him already dead. However, he kept on writing and it is to that period that many of his best loved poems belong. He lived in poverty and subsisted on the alms of his relatives; Liiv returned to social circles in 1902 and a year later a group of young authors named Noor-Eesti (Young Estonia), encompassing several of the later coryphaei of Estonian literature and linguistics – Friedebert Tuglas, Gustav Suits, Johannes Aavik et al – set up a collection of funds with the aim of publishing a book of Liiv’s selected poems, released in print a year later. The decade to follow saw two more collections of Liiv’s poetry released, as well as a book of his prose miniatures and remarks. In the later years, Liiv succumbed again to his illness and became delusional. He passed away in December 1913, due to tuberculosis.

It was in the spring of 2017 that a long-planned monument to the victims of Communist regime was opened at Maarjamäe in Tallinn, dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives or suffered cruelties under the yoke of Soviet occupation. The monument consists of two parts, a long dark corridor of stone plates with the names of the deceased, and at the end of it, a little open field or a valley called “the nest”. There, the wall carries a quotation from Juhan Liiv’s poem “She Flies To A Beehive”, which begins,

Flower to flower she flies,

and she flies to a beehive;

and should a thunder cloud rise,

she flies to a beehive.

And thousands will fall,

but thousands will reach home,

they won’t let sorrows abide,

for they fly to a beehive!

Beehive is, naturally, an image of a homeland and it is emblematic of Liiv’s deep love for his country which, for him, was identical with love for one’s self. At the same time, the image of a beehive corroborates the need of a collective consciousness in order to survive “the thunders”, the trials and tribulations of times, and it is also indicative of the idea that survival is possible by collecting the fulfilling essence of land, availing oneself to its gentle gifts thankfully, even prayerfully. A beehive, just like a country of one million, is no doubt a small unit, but it’s still a world in itself, and one that needs a number of qualifications to fall in place.

Apart from weaving the nation together with nature – a perception crucial to the Estonian people – the poem, written in 1905, is almost prophetic. For it could well be a description of the fate of Estonians in the 1940s and 50s when thousands did fall – on their way to war and deportation – and thousands still reached back home, so as to keep the “beehive” of the Estonian nation, culture and language alive. In Miina Härma’s, as well as Peep Sarapik’s composition, the poem is also a well-known choral song, often a pivot of our song celebrations.

Two other seminal poems of Liiv have found an expression in popular music. “Our Room Has A Black Ceiling” was made into a song in the 1980s by the rock group Vitamiin. Its release was accompanied by a very avant-garde music video where the band members were so heavily covered in make-up that they almost appeared to be wearing masks. The recitative style in which the words of the poem were rendered gave something of an inhuman feel to the piece. The song caused quite an uproar in its time, particularly for the inclusion of the lines,

Our room has a black ceiling,

and our time does as well:

it writhes as if in chains ‘twas bound —

if only it could tell!

These were then seen by many as hidden criticism of Soviet rule, as well as a suggestion that not much had changed in people’s lives since the time that Liiv had written this poem.

It should be noted though that the black ceiling in the poem is both a metaphor and description. Ceilings of many of the old Estonian farm houses were black from smoke and soot; the oldest and poorest had no chimneys and were called smoke houses, they might have also been saunas inhabited by farm hands who could not afford, or were not allowed to possess their own dwellings. Smoke had a practical function, for it protected the wood from decay and vermins, yet in Liiv’s poem the black ceiling becomes an epitome of Estonian history, viewing the country as a place of dark past and bereft of any welcoming future. After centuries of foreign rule and oppression, forever living as a nation serving others, there was a sense of blackness hanging over people’s daily toil. Liiv expresses the resulting sense of hopelessness, but the poem is also a tribute to the people who kept their integrity despite hardship and little outlook for an improvement.

Curiously enough, the poem is also the reason why the ceiling of the main reading hall of the Estonian Writers Union is coloured black – as an act of homage to our great national poet. It also relates though to Liiv’s poem “My Party”, where Liiv claims that the only party he is willing to belong to is that of the Estonian language – an idea which has been something of a credo for the Writers Union here.

The poem “Yesterday I Saw Estonia” was turned into a protest song by the rock band Ruja – in the same period of the 1980s. Written originally by Liiv while travelling by rail across wintry Estonia, it is possibly the most quoted poem in the whole of Estonian literature. Its references can be found in the poetic works of a number of authors, including Triin Soomets, Kivisildnik and Jüri Talvet, the last referring to it in the form of negation, i.e. “yesterday I did not see Estonia”. In all cases, the line is used for describing the uncovering of some unpleasant truth, and usually a truth preferably ignored. Liiv mentions farm houses in disrepair, the poverty of households, the puny fields, the fields overgrown with thickets and eventually, the moral and spiritual downfall of the country. Unlike some of Liiv’s other poems, this one lacks an elevating finale, but succumbs to the feeling that something is irretrievably lost. Though carried by concern, as much of Liiv’s writing about his homeland is, the heart is taken over by despair and grief.

Looking back at Liiv’s oeuvre in general, it is striking to see how timeless his pieces are – for apart from their somewhat archaic language and stylistics, these poems could well have been written by some present-day author. The reason behind is this probably that Liiv has no socio-political agenda to represent and his poetics were carried by a very personal as well as universal concern for the well-being of one’s home and country.

Admittedly, much of Liiv’s poetic world is rather dark and melancholy, his landscapes are dominated by swathes of cold, and winds, and emptiness. Life, as described here, is hard and its toll relentless. And yet Liiv celebrates that very life and the sorrowful, dusky landscapes with an equal relentlessness. Hardship makes one pure and in purity, there is always beauty. Perhaps this is why Liiv’s writing holds the great quality of redemption, as he himself emerges almost like an unwilling martyr – a perception only heightened by his factual lunacy. Liiv’s work is often shown to describe the depressiveness of Northern lands, and yet it is love that lies at the core of his credo. Liiv is, no doubt, a poet of the land, it is in the fields and forests and villages that he sees the heart of his country throb and develop. It is there that he truly finds himself, as evident, for example, in the poem “The Forest”,

Stop and stay here,

thought-laden head,

heart sick with sorrows,

here the soul is at ease!

Liiv gave the Estonian language an example of simplicity and conciseness, as well as one of sympathetic honesty – “where deceit is, flee from there,” he exclaims in one of his poems. There is something very informal to his poetry, even though most of his poems follow meter and rhyme; they feel natural, almost casual and in that, unpretentious and truthful. The poet does not hide himself behind his words, he rather finds himself there, more naked than before. The outward simplicity of his poems isn’t merely a simplicity of form, but also that of content, it is a way of enacting the poem to reveal the inevitable. Even if Liiv’s overwhelming modesty about himself led him to believe and claim that he is not a poet at all.

In some way, Liiv’s language also reflects the asceticism of his landscape; one needs simplicity and truthfulness in such demanding settings in order to survive. He feels the suffering and joy of the land as his own, suggests being wedded to the land in the poem “The Autumn Sun”, or exclaims “unhappy I am with you, still unhappier without you” elsewhere. The strong connection to the land allows him to be, on one hand, a very earthy writer and yet by the tint of his witnessing the deeper quality of that connection, a poet of the spiritual. And more than that, via media his words Liiv induces us to live up to that same standard; it is thereby that his work has become almost like a measuring rod for the rest of the poetry that has followed.

Mathura is a poet, writer, and three-time nominee to the Juhan Liiv Poetry