Ilmar Laaban, often called the father of Estonian Surrealism, was born on 17 November 1921 in Tallinn. Between 1939 and 1940 and again in 1941 -1942 he studied composition and piano at the Tallinn Conservatory. From 1940 to 1943, he was a student of Romance languages at the Department of Philosophy of the University of Tartu. In 1943 he fled from the German army via Finland to Sweden.

Between 1943 and 1949 he continued his studies at Stockholm University where he read Romance languages and Philosophy. After that he worked as a freelance writer, publicist and lecturer in Stockholm. Amongst other things, he was a Scandinavian correspondent at various elite French and Italian magazines. In Swedish cultural circles, he won recognition with his series of radio broadcasts about modern French art. He also lectured on French art at several universities in the USA. Since 1975, he has been a member of the International Art Critics Association.

Ilmar Laaban began publishing poetry in 1938. His collections of poems in the Estonian language The End of the Anchor Chain is the Beginning of Song (‘Ankruketi lõpp on laulu algus’, 1946) and Rroosi Selaviste (1957) were published in Sweden. The End of the Anchor... derives from the Bretonesque main trend of Surrealism. ‘Rroosi Selaviste’ is a bit closer to Pataphysics – a trend which separated itself from Surrealism. Its most remarkable representatives in France were Raymond Queneau and Michel Leiris. The turn-of-the-century French dramatist Alfred Jarry (King Ubu, Super-Males), who is considered to be the forerunner of Pataphysics is among Laaban’s favourite authors. Laaban’s third collection in the Estonian language, Poetry of My Own and of Others (‘Oma luulet ja võõrast’) was published in Tallinn in 1990. This collection includes previously published poems as well as 73 unpublished poems.

Ilmar Laaban has translated into Estonian poems by G.Apollinaire, Ch.Baudelaire, J.Cocteau, P.Emmanuel, H.Michaux, P.Reverdy, A.Rimbaud, J.Arp, P.Celan, E.Grave, Chr.Morgenstern, R.-M.Rilke, N.Sachs, W.Blake, J.R.Jimenez, F.G.Lorca, G.Ekelöf, E.Lindegren, B.Malmberg etc. Laaban has also translated Estonian poetry into Swedish and German, and French poetry into Swedish (the collection 19 Franska Poeter together with E.Lindegren). The collection of Laaban’s work under the title Skrifter began appearing in Sweden in 1988 (volumes 1-4).

Starting from the 1960s, Laaban has produced Sound Poetry. This kind of poetry (if indeed it can be called poetry) is primarily meant for the ears rather than the eyes. What matters is the timbre; the meaning of a word – if there is any – is secondary. In the humming of the sound poetry, in vibration, play of tones and the gradually increasing lung activity, it is often not possible to distinguish words. Sound Poetry exists on the border of poetry and music. Laaban with his education in music was in excellent position to write such poetry.

Throughout the period of Soviet occupation, Laaban’s poetry was forbidden in his homeland. A momentary exception to this was the political spring of 1956. But summer never arrived.

In 1967, a bulky anthology, Estonian Poetry, was published in Tallinn. The publisher was brave enough to include poetry by several Estonian poets in exile. For some reason, Laaban’s work was not among them.

The Biographical Lexicon of Estonian Literature, published in Tallinn in 1975, as well as the ENE (Encyclopaedia of Soviet Estonia), also ignored the existence of Ilmar Laaban.

Forbidden fruit is always sweet. Laaban’s work, ignored and strictly forbidden, spread the more rapidly in manuscript form. His poetry was eagerly circulated by Soviet-era students of the Humanities. It was only in 1988, during the active de-Sovietisation period that Laaban was again published and fully appreciated at home. In addition to his collection of poems published in 1990, another book appeared in 1997. The latter, titled The Skin of Marsyas (Marsyase nahk) was rather more bulky, containing Laaban’s critical and theoretical articles,

In his article Perspectives of Surrealism (Sürrealismi perspektiivid), dating from 1944, Laaban wrote:”The aim of Surrealism is not to replace scientific reality with that of the Unconscious, but to merge them, thus forming a new surreality. In the process of its creation, an automatic text or a science fiction story merely act as initial steps.”

This very much holds true for the whole work of Laaban himself.

Piecing together the ideas of Gerard de Nerval, Andre Breton and the USA based literature professor Aleksander Aspel, one might say that a Surrealist exists on the narrow bridge between madness and sanity and seeks a point in our minds where life and death, reality and fantasy, future and past, the expressible and the inexpressible no longer seem contradictory. The bridge itself is narrow, but eyes that have the ability to synthesise, like Laaban’s, can enjoy a surprisingly expansive view.

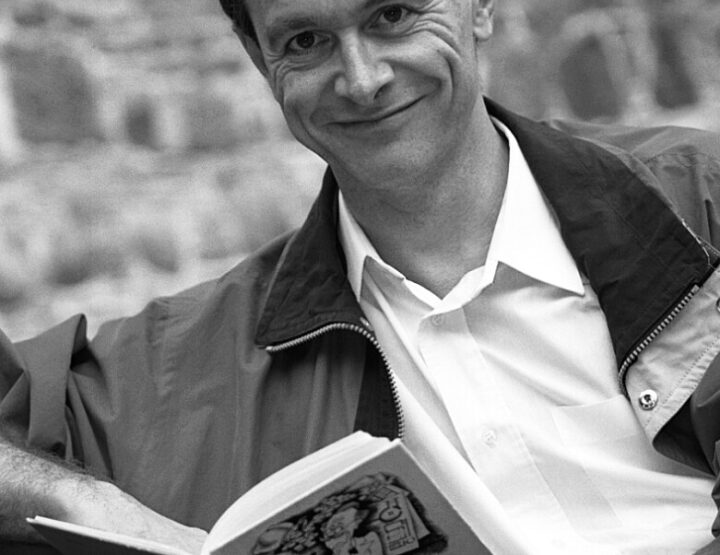

Laaban. Broad view from a narrow bridge

By Andres Ehin

–

Share: