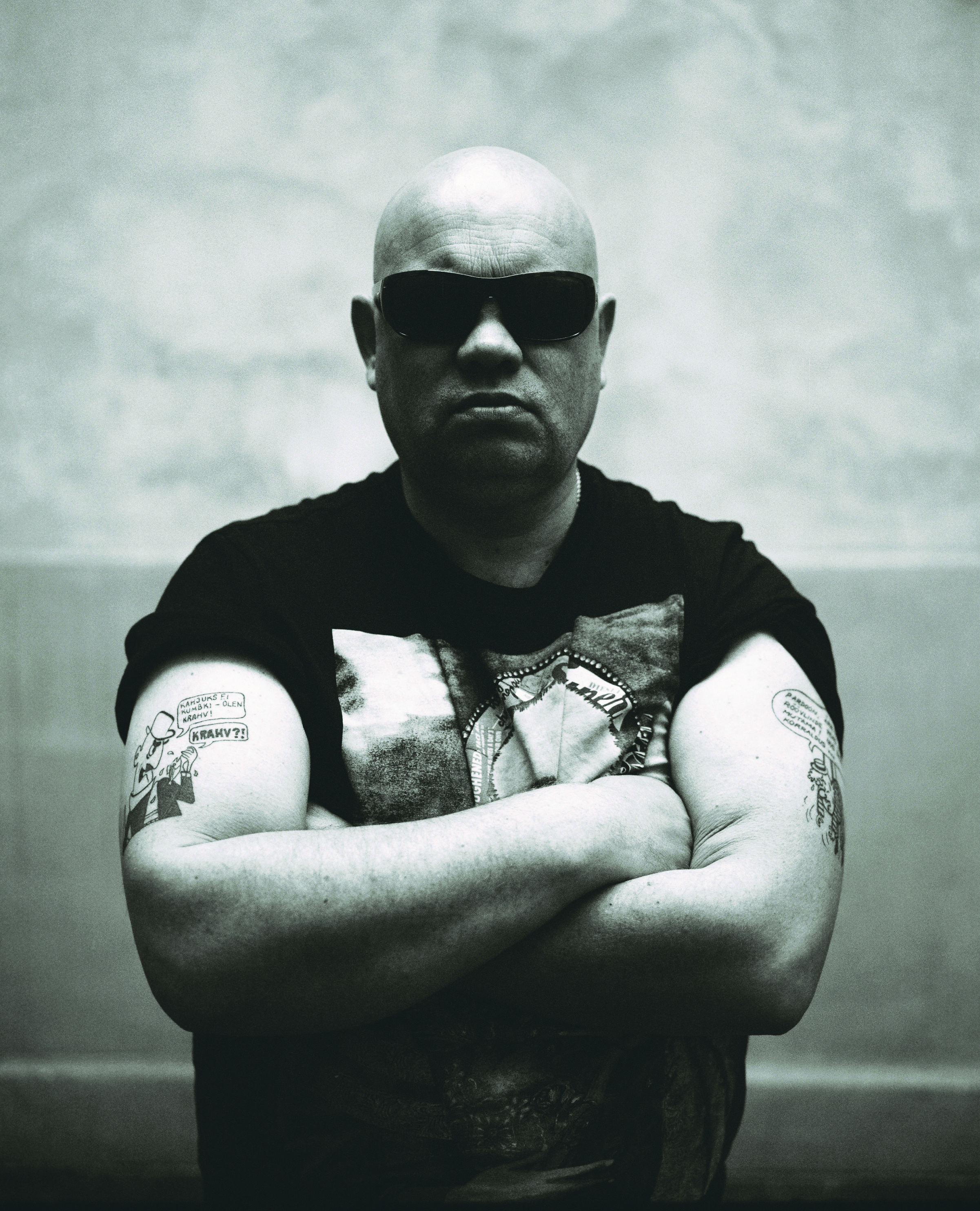

I last saw Paavo Matsin (1970) at a museum that honors the Estonian literary classic Eduard Vilde, where we were both scheduled to speak. We chatted shortly before taking the stage, and I suddenly noticed the tattoos on Paavo’s hands, tattoos I didn’t remember him having before. One caricature stood out most: a barrel-shaped man wearing a striped shirt and checkered pants with suspenders, an impressive shock of curly hair sprouting from his forehead, crowned by a miniature cap. Coming from the figure’s mouth was a speech bubble containing the famous words: “Adjöö, musjöö!” (1)

I recognized Ponchik immediately! Ponchik and Babyface: legendary “bad boys”, led by the infamous Count. True, the Count later became a law-abiding businessman, while Ponchik and Babyface unfortunately stayed true to their criminal habits, and received the punishment they deserved.

To explain, for those entirely confused by the above: Ponchik, Babyface, and the Count were characters in one of the most-loved Estonian comics series of all time, the author of which was the caricaturist Olimar Kallas (1929–2006). It was not a “series” in the Western sense, as Kallas published only eight of his “Kiviküla” (“Stone Village”) comics. The first book in the “Stone Village” series, 3 Stories, was published in 1979 – back when both Paavo and I were children. Kallas can be regarded as a cult author, and it isn’t hard to determine why his fan base includes so many contemporary writers: the “Stone Village” comics were not merely well-drawn, but also skillfully worded. I know more Kallas quotes by heart than I do those of Estonia’s literary classics. Oh, what joy it is to cite the Count when another character angrily asks him: “Are you a chunk of ice or a person?” “Neither, unfortunately – I’m the Count!”

But why discuss this here at such length? I should be speaking of Paavo Matsin, not Olimar Kallas, and I should be addressing Matsin’s writing, not his tattoos. However, the Ponchik tattoo on Matsin’s arm speaks worlds not only about his personality, but also about his creative works. Not every man has a marginal literary character etched into his skin, and this was not only a conscious act, but part of an agenda. First of all, one can’t deny that Matsin himself somewhat resembles Ponchik in appearance. Similarly, the “bad boy” metaphor certainly applies to him in the context of Estonian literature. Matsin’s literary success is at least partially due to the fact that he stays voluntarily at the margins. He is an author who disregards the rules and tells them “Adieu, monsieur!”, and much more successfully than Ponchik.

There is another factor. It is often difficult to determine where Matsin’s everyday life ends and where literature begins, at what point the fireworks of fantasy will burst out above the ordinary. His transitions from one to the other are fluid. Life transforms into theater in Matsin’s hands, even without the scenery. He proved this well that time at the Eduard Vilde Museum. We had been invited to interpret one of Vilde’s most wellknown novels, The Milkman of Mäeküla (Mäeküla piimamees, 1916), which is regarded as a cornerstone of Estonian psychological realism.

Matsin began by saying that he finds realism boring. He was the only speaker who refused the museum’s request to give an interpretation of the classic’s work. Instead, Matsin told colorful tales about when he himself worked at the Vilde Museum. They sounded both credible and incredible, once again proving to me that Matsin lives a style in which the transition from reality to imaginary is neither abrupt nor unambiguous. Life can be more vivid than fantasy, and thus life itself can be told as fantasy. At the same time, a good fantasy can revivify life: – take for example the early years of Matsin’ literary activity. The author was a member of the avant-garde literary group 14NÜ, which released outlandish publications, including their “strip books”, which experimented with the limits and opportunities for expression offered by both books and language. 14NÜ was a motley crew: in addition to Matsin, it included the internationally renowned animated film director Mait Laas, and Maarja Vaino, who is now the director of the A. H. Tammsaare Museum. Also in its ranks was a long-dead author: Johannes Üksi (1891–1937), a marginal poet of the early 20th century. But possibly the most interesting member of 14NÜ was Marianne Ravi. To this day, I am unsure whether Ravi is a real person or a phantom from the brains of Matsin & Co; still, she was credited as authoring one of the group’s “strip books”. When I hypothesized in an essay that Ravi is a figment of the imagination, Matsin and Laas tried with all their might to prove to me that she exists. It turned out that Marianne Ravi works at an Italian television station. I was given a videocassette to watch. What I viewed was, to put it mildly, a clip of a bizarre weather forecast. Standing next to a map of Italy was a stunningly gorgeous nude blonde woman, whose vagina, belly, and nipples were covered by a sun and various clouds. As a vivacious voice reported the weather, the woman started removing the clouds and sun from her body, one by one, and attaching them to the map. That weather girl wearing a brilliant smile was apparently Marianne Ravi.

Additionally, I was sent a photograph of a young woman seated between Matsin and Laas at a café, giggling into a glass of juice. Written in Italian on the back of the picture was: “To my dear Jan. Marianne.” Despite all this evidence (or thanks to it), I like to think that Marianne Ravi really was imagined by Paavo Matsin and Mait Laas. The Marianne “case” remains indicative of Matsin’s works, although the author has now shifted away from his somewhat rowdy genre games and come significantly closer to traditional forms of written expression. I miss 14NÜ’s unusual book presentations, for one thing. At the presentation of Matsin’s experimental work Aabits (ABCs, 2000), for instance, a gymnast wearing a white unitard performed various exercises while a Catholic prayer was read. It was not a presentation, but something much broader: the event gave literature a performative dimension, transforming it into a surrealist effort of sweat and strained muscles. It was the most theatrical presentation I’ve ever seen, a performance whose

participants were anything but ordinary. Marianne Ravi and her little tufts of clouds can also be regarded as participants in an absurd, stimulating performance staged by Matsin himself.

Perhaps it would be useful to characterize everything Matsin does as performances, including his novels. Matsin’s book covers are stage curtains, behind which words and motifs create a mise en scène that would do honor to even the most avantgarde Theater of the Absurd. His books are performances of perception punctuated by the dented trumpets of forgotten rituals, mysterious hand organs, and rat-catchers’ pipes. Matsin is ideally suited to be the director of a magical theater, behind a mirror or around a dark corner, one that is both cozy and labyrinthine. His performers could include breathing mummies and a disintegrating God, like in the peculiar house in Ingmar Bergman’s film Fanny and Alexander. Matsin’s works are an orchestrated spree of free-form associations.

But what is the source of these free-form associations? The title of Matsin’s first novel is explanation enough: Doctor Schwarz. The 12 Keys to Alchemy (Doktor Schwarz. Alkeemia 12 võtit, 2011). As one might guess, Matsin utilizes in the text his thorough knowledge of the occult and alchemy, as well as everything associated with the two. In 2003, he defended his thesis “Carl Gustav Jung and Alchemy” at the Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church’s Theological Institute, and he is also a great fan of the works of Gustav Meyrink. Doctor Schwarz, however, does not merely describe alchemy; the text itself is a kind of symbolic alchemy, taking the traditional forms of storytelling and attempting to achieve something new by mixing and transforming them. In the same way that alchemy used elements of chemistry, physics, astrology, medicine, art, and mysticism, so Matsin takes various means of literary expression and conjures a new quality out of them. In a review of Matsin’s work, the critic Meelis Oidsalu wrote: “Doctor Schwarz [appears to be], among other things, an attempt to create a textual substance that is purified of the

‘traditional’ story-, character-, and plotbased literary perception; one that spotlights the archetypal relationships between author, literature, and reader.” Literature abruptly breaks out into dance and the stage spins, exposing odd rituals. Rabbits and angels holding up tarot cards leapf out of the theater director’s hat (which is also his head). This could all be classified as postmodernist, but something prevents me from doing so. The price of the viewer’s birth in Matsin’s textual theater is the author’s life, not his death. More simply put: you can’t really understand anything, but it’s spectacular!

Matsin’s second novel The Blue Guard (Sinine kaardivägi, 2013) moves towards a more traditional style of storytelling. The stage is set in Riga, the largest city in the Baltic States, among its grandiose architecture. Both historical and mystical elements set off the book’s chain of nail-biting events. One important setting is the apartment-museum of Aleksandrs Čaks (1901–1950), one of Latvia’s most renowned progressive urban poets, whose works were long banned in the Soviet Union. In the novel, a clash breaks out between the “baggypants” (a reference to the proletariat, but it could also be to modern liberalism) of Riga’s outer neighborhoods and the semi-legendary, slightly aristocratic Blue Guard, a militant volunteer unit of Riga residents, which is known to haunt St. Peter’s Church in the city’s Old Town. The Blue Guard’s association with a university fraternity is a nod to Matsin’s second greatest topic of interest, after alchemy: Freemasonry. None of this should be taken too seriously, of course. Matsin’s performance is always speckled with comic motifs, one very conspicuous proof of which is that he adapted his own name as author to a Latvianized version: Pāvs Matsins. This is also the name of the book’s narrator, who works at the Čaks Memorial Apartment. Still, Matsin doesn’t refrain from furthering his own cause in The Blue Guard, i.e. keeping alive the belief that a mental and creative alchemical style founded on foolhardy experiments and free association is an important tool to prevent intellectual assimilation. The performance not only centers on Matsin: it happens within him – in his head and his imagination – and the opportunity to allow our fantasy to flow freely and uninhibited (as well as to take part in this performance) is more

important than we can ever understand.

Matsin’s third book, The Gogol Disco (Gogoli disko, 2015), turned out to be a breakthrough for the author: it received both the Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Award for Literature and the EU Prize for Literature, and reached the top-ten list at Estonian bookstores. A few of Matsin’s more avant-garde calling cards, such as a cryptic plot and intertextuality that is impenetrable to the layman, continue to recede in the work, although elements of his textual performance are amplified that much more powerfully: a bizarre, dream-like atmosphere, an abundance of colorful characters and situations, and the carnival of fantasy they work together to create. Matsin does write linearly in The Gogol Disco, but does not shed his talent of conjuring a unique world that is magical and grotesque, one that refuses to yield to classification, e.g. in terms of genre. The novel tells of a near future (or a parallel present), in which Imperial Russia has put an end to Estonian independence, and Estonians themselves have dwindled to a scant minority in their homeland.

However, the work is not centered on national apocalypse. It focuses instead on a visit by the literary classic Nikolai Gogol – raised from the dead – to Matsin’s tiny, picturesque hometown of Viljandi. There, the writer invigorates the local intellectual scene, and on several occasions flips it upside-down. Nevertheless, Gogol – in whose depiction Matsin seems to have taken inspiration from Jesus, Woland, and Golem – is not necessarily the main character of The Gogol Disco. At center stage is a diverse gallery of mainly Russianspeaking local intellectuals and servants, whose already odd lives intersect with and are permanently transformed by that of the parable-mumbling Golem/Gogol. The setting of The Gogol Disco could be called a gamboling dystopia, or even a parody of a dystopia. In another respect, one could say it is parabolically grotesque. In any case, Matsin’s soaring imagination leaves most other Estonian fantasy writers shuffling, with both feet planted firmly on flat lands.

It certainly must be mentioned that The Gogol Disco possesses a clear bonus: the both typical and exceptional small Estonian town of Viljandi, which the author depicts with the same degree of affection as he does Riga in The Blue Guard. I pass through Viljandi frequently, seeing as how my summer cottage is located nearby. One of my favorite places in the town is a tiny, cozy antique store on Lossi Street, the type of place where you can tangibly feel time slowing down, or even stopping. I was nearly ecstatic when I saw that Matsin had made it one of the novel’s primary settings: two simple rooms packed full of books. The author’s description of the shop, and of the town as a whole, is both humorous and accurate. In some ways, Viljandi is entirely recognizable, while in others it clearly comes from Matsin’s restless imagination: more likely than not, Estonia, with its declining population, will never see trams in towns the size of Viljandi. But if trams were to run there, they would certainly fit in. Thus, the Viljandi of The Gogol Disco is strange and familiar at the same time. The authenticity of the setting and the bizarreness of the events that unfold there could lead one to classify Matsin’s work as magical realism; however, the images Matsin conjures are too restive, the sense of liberty surging from his books too powerful, and his performance too diverse in nature to be limited to such a definition.

At that same literary evening in the Vilde Museum, Matsin remarked that he had spent time at an artists’ and writers’ house abroad to write his newest, fourth novel. The protagonists of this forthcoming book are not people, but birds: storks, to be exact. During his creative residency, Matsin discovered that the cheapest food at the nearest supermarket was grilled chicken. And so, Matsin told me how he wrote about storks and ate chicken for days on end. I envisioned him sitting in his room, the tattoo of Ponchik on his arm, every corner of the space piled high with chicken bones, and a stunning array of storks before him: big and little, black and white, male and female. The image could have come straight out of one of Matsin’s own books. There is a truly Beckett-like atmosphere to the scene as I imagine it. What could this mean? Doubtless that if you speak with Paavo Matsin, he will make you, suspecting or not, a part of one of his countless performances.

Jan Kaus (1971) is a writer and musician. He has published five novels, and has also authored poetry, essays, novellas and miniatures. In 2015, Kaus’ novel Mina olen elus (I Am Alive) and miniature collection Tallinna kaart (A Map of Tallinn) won the Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Award for Prose.