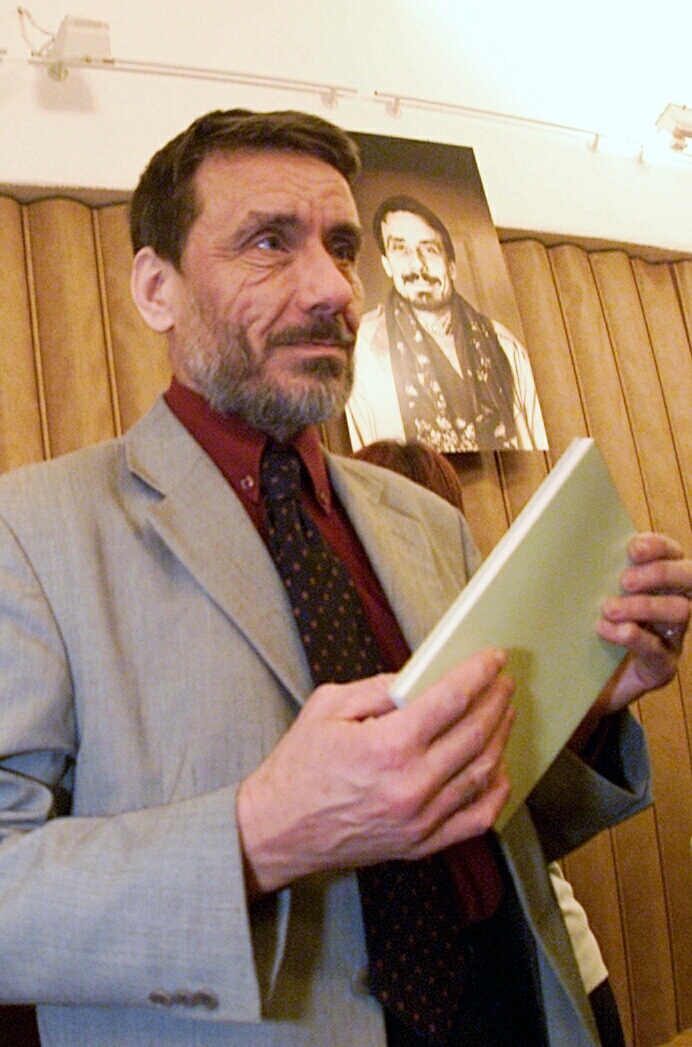

Paul-Eerik Rummo, one of the major authors of the Estonian poetry innovation of the 1960s, was born in 1942 in Tallinn to the family of writer Paul Rummo. He went to school in Tallinn and then studied Estonian language and literature at Tartu State University (now Tartu University), graduating in 1965. Between 1979 and 1986 he was literary editor of the Estonian State Drama Theatre in Tallinn (now the Estonian Drama Theatre) and in 1987-1989 head of the Estonian Writers’ Union. Together with a number of Estonian cultural figures, he signed a letter of protest in 1980, which was sent to both Estonian and Soviet leading daily papers. The authors spoke out in defence of Estonian culture and language and protested against intensifying Russification. This became known as the ‘letter of the forty’. Since Estonia regained independence, Rummo has almost retreated from literary life and been active in politics: in 1990-1992 he was cultural consultant at the State Chancellery and in 1992-1994 Minister of Culture. Between 1994 and 2003 he was a member of the parliament and since 2003 he has been the Minister of Population Affairs.

Rummo began writing poetry at an early age, debuting in 1957 and publishing his first collection, Ankruhiivaja (Anchor Heaver), in 1962 in the first poetry cassette of young authors. This was a series where many young authors were able to publish their work for the first time. During the 1960s Rummo published three collections of poetry; besides Anchor Heaver, he also published Tule ikka mu rõõmude juurde (Always Come to My Joys, 1964) and Lumevalgus … lumepimedus (The Blinding Light of Snow, 1966). A collection of selected poetry, Luulet 1960-1967 (Poems 1960-1967), which, in addition to what was published before, contained a new cycle titled Läbi peo mul voolab puu (Wood Flowing Through My Palm), appeared in 1968.

By the late 1960s Rummo had become one of the most significant authors of the decade, his work a part of the ‘high poetry’. However, a nearly ten-year gap then ensued before he published again. His next collection, quite singular against the background of his own poetry and the Estonian poetry tradition in general, was Saatja aadress (Sender’s Address). The manuscript was completed in 1972, but was not approved by the censors and remained unpublished for a long time. Some of the poems from Sender’s Address appeared in 1985 in the collection Ajapinde ajab (Splinters of Time), and all of them were published in the already changing political circumstances in 1989 in the book titled Saatja aadress ja teised luuletused 1968-1972 (Sender’s Address and Other Poems). This collection received the Writers’ Union annual award in 1990. In addition to the above-mentioned, Rummo has published the collection of poems Kohvikumuusikat (Café Music, 2001), the selected poems Oo, et sädemeid kiljuks mu hing (Oh if the Shrieks of My Soul Were Sparkles, 1985), and Luuletused (Poems, 1999). In 2005 most of Rummos’ poetry appeared in the collection Kogutud luule (Collected Poems). His poetry has been translated into various languages, the collection The September Sun (New York, 1981) in English.

Paul-Eerik Rummo is also the author of one of the major plays in Estonian theatre innovation of the late 1960s – Tuhkatriinumäng (Cinderella Game), published in 1968 and performed the following year in Tartu. The play, sometimes regarded as a paraphrase of Rummo’s earlier poetry, uses the structure of the Cinderella tale, focusing on the existential labyrinth of human life and constant seeking of truth. Cinderella Game managed to introduce Estonian theatre innovation beyond the borders of the Soviet Union – the manuscript of the play reached exile Estonians and was staged in 1971 at La Mama Theatre in New York. Other plays by Rummo are Pseudopus and Eagle-Prometheus (both 1980). He has also written film and theatre scripts, radio plays, essays, reviews and lyrics for many songs.

From the point of view of Rummo’s own poetry and the Estonian translation tradition, his activities as a translator of poetry deserve special attention. He has translated poems from Finnish, Russian and English by authors such as Paavo Haavikko, Tuomas Anhava, Aleksandr Pushkin, Ronald David Laing, Dylan Thomas and Thomas Stearns Eliot.

It is difficult to find something that would characterise Paul-Eerik Rummo’s poetry as a whole – both the manner and tone of his poetry have changed through the years. Compared with his later work, Rummo’s earlier poetry, mostly what appeared in Anchor Heaver, has a brighter world view and more optimistic manner. The title suggests the main motif – setting off on a journey, filled with hope and looking towards the wide expanse ahead. This kind of mood perfectly suited the changed situation in the early 1960s, when the Soviet regime was somewhat mellowing and all kinds of restrictions were relaxed. Hope and perception of the wider world carried on to the next collection, Always Come to My Joys, although the youthful zeal seems to have retreated here and more serious tones have crept in, together with a sense of danger and realisation of life’s fragility, which is especially typical of the short cycle Hamleti laulud (The Songs of Hamlet). Against the general background of the Estonian poetry tradition, Rummo’s earlier poems can be partly seen as a continuation of pre-Second World War poetry – it is highly poetic neo-symbolism where sound, abundant imagery and lyrical metaphors dominate. Word-play is also apparent.

By its manner, Rummo’s next collection, The Blinding Light of Snow, seems to suit the first period, signifying, however, a considerable change of mood and topics. The general excitement and hope of the 1960s began to ebb at the end of the decade – it became increasingly obvious that there were limits to liberation and the thaw era was followed by a new period of rigidity. In the late 1960s joyous attitudes were replaced by anxiety and hopelessness. In poetry, Rummo’s The Blinding… can be seen as a harbinger of this change. What prevails in this collection is existential anxiety: man’s social and also emotional solitude is depicted against a global background. A perception of the tragedy of the times and the history of his homeland blends with a sense of insecurity. Social topics and criticism have become more acute as well. The artistic and thematic wholeness of the collection has often been pointed out: The Blinding… is not a mere collection of poems written during a certain period of time, instead it expresses one experience, perception of life and worldview.

Entirety is essential also in his next collection of poems, titled Saatja aadress (Sender’s Address; despite the much later publishing date, I nevertheless consider this as the next one, relying on the date of completion of the manuscript). Sender’s Address is a kind of programmatic whole, characterised by sharp social emphasis and unconcealed political motifs. The manner of poetry has here totally altered – the earlier highly poetic and abundant imagery is replaced by spoken language and laconic expression; this has often been called a journalistic style. Emphasis on the possibility of word-play is greater here. Neo-symbolism is replaced by a type of poetry that could be regarded as an echo of Anglo-American high modernism in Estonian poetry: it is extremely image-conscious and erudite. The tone is serious and straightforward, occasionally sarcastic. The poet determines his own position and that of his homeland and people ‘in a rather small country, which happens to have its own government /in a rather big country, whose might and peculiarity are for us / obligatory’.

Political motifs in poetry constituted a complicated phenomenon during the Soviet occupation period. Poetry of that period has often been characterised as using the Aesopian language, concealing elements of opposition and social criticism into ambiguous images. There is always the problem of how many of the political motifs are written into the text on purpose and how many are imagined to be there by the reading public. Rummo’s Sender’s Address stands outside this particular issue – everything political is honest and straightforward. It is therefore not surprising that the work was initially banned and, after longlasting negotiations, Rummo took his manuscript back from the publishers. The poet then retreated from the Estonian literary scene for about ten years, which the reading public perceived as ‘meaningful silence’. It was especially marked as by the late 1960s Rummo had already become one of the most significant and highly acclaimed poets among the general public, and his silence could not go unnoticed.

The manuscript of Sender’s Address was, in the meantime, read widely as an underground publication. The first written review was published also in an underground magazine Vigilia III in 1973. The collection of poetry was thus placed in its rightful time, which was certainly essential as far as reception was concerned: in 1989 when Sender’s Address was finally published, the situation had changed drastically, both politically and in regard to developments in poetry. In the epilogue of the collection, Rummo admitted the inevitability of the relationship between poetry and its time: ‘Poetry is of course not merely the fruit and expression of its time of birth. It nevertheless cannot fully escape it either.’

Despite its sensitivity to situation, we cannot really say that Rummo’s poetry in general, or Sender’s Address in particular, simply reflects daily existence. First of all, his is an existential poetry that perceives possibilities and limits, both temporal and spatial chances and inevitabilities, and synthesises the world in man and man in the world. The changing mood and manner of Rummo’s poetry over the course of time reflects the expansion and opening out of the possibilities in poetry and the poet himself. Expansion and openness would perhaps describe Rummo’s position in Estonian poetry. It would be difficult to name any other poet as the follower of Rummo. However, this does not mean that Rummo’s poetry is somehow reclusive or that it stands apart against the background of the general Estonian poetic landscape. Quite the opposite: his work amasses so many benefits and possibilities of poetic innovation that it is only there where real synthesis takes place, forming basis for new trends. Even if we do not see directly Rummoesque authors, we do see something of Rummo, in one way or another, in the work of many poets. Although Paul-Eerik Rummo is currently more active in politics than in poetry, he published a bulky collection of his poems and received the Estonian Cultural Endowment annual award last year. This shows that, even though poetry cannot totally escape its time, poetry can reach beyond time and remain meaningful at all levels – not abandoning time but carrying it along with it. In that sense, Paul-Eerik Rummo is not a current politician and former poet – he remains a poet.

© ELM no 22, spring 2006