Kadri Hinrikus, an Estonian children’s literature author, first became known to most of the local population as a TV news anchor. Her hobby of writing children’s books naturally couldn’t stay secret for long. Hinrikus’ first book Miia and Friida was published in 2008 to immediate warm reception. Her ninth book Catherine and the Peas (2017) was nominated for the Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Award for Children’s Literature and received the Tartu City Library’s Children’s Literature Award.

All signs pointed to the time being right for Hinrikus to close the chapter of her television work and dedicate more time and space to writing. Sitting at a café in downtown Tallinn, it’s plain to see that Hinrikus is happy and content: as she herself remarks, every positive word and recognition gives her joy. “An award does give you good energy. It gives you a sign that your works and message have hit home, and that is extremely important. It’s the quintessence of joy,” she says.

Modern-day problems and fears

Hinrikus’ first children’s book, a memoir about her parents’ lives titled Miia and Friida, was published a decade ago already. Has she changed as a writer? Are the topics that speak to her now different? Hinrikus confirms they are. “I very much hope that I’ve developed over that period of time and that every book has taught me something. Over the last few years, I’ve been fascinated in particular by the lives of children today; by their problems and fears. For instance, the fear of whether they’ll find friends at a new school or of their parents working abroad. A mother’s death, divorce, new family structures… Worrying that no one has time for anyone else in their family. Serious topics like those.”

Hinrikus’ books are also meant for parents to read to their children. Her latest, the awarded work Catherine and the Peas, tells of a father leaving his family and his daughter coming to grips with the situation. “Parents have told me they’ve read and discussed it together. That makes me happy. I’ve also had great encounters with schoolchildren. One time, there was a little girl sitting in the front row who spoke up during the Q and A session and told me: ‘Your books are so great.’ It wasn’t even followed by a question. It was very moving.”

Hinrikus receives an ample amount of speaking invitations but accepts far from all of them. “A writer’s job is to write, not to be traveling around all the time. I’d like to have time for writing,” she says.

At the moment, Hinrikus is already working on a new book titled Don’t Worry About Me, which should be published in Estonian this fall. The work is a fairy-tale-like story set in a forest where mysterious creatures cohabitate and fly around with the animals, birds, and beetles. Topics she addresses include solitude, friendship, fears, the freedom to be just the way you are, and the fact that sometimes love and caring can turn harmful.

“Children shouldn’t always avoid solitude, either. Some kids actually need solitude a little more than others,” she says, adding that it’s not ideal for all children to constantly attend various practices, participate in clubs, or hang out with their peers.

Everything settles in people

Hinrikus, who grew up in central Tallinn and currently lives in the Uus-Maailm district, has felt a strong pull towards books and reading her entire conscious life. “I was read to a lot when I was really little, and that’s how I became a big reader. My favorite subject at school was Estonian language and literature, I was keen to write essays, and I attended a literature-intensive class in high school.” Now, as an adult, quality time for Hinrukus means the days she’s able to push other obligations aside and work on writing from morning till evening, or to read a good book and truly delve into it.

“Everything settles in people. Just like [the Estonian classic] Ristikivi wrote: ‘even a lizard’s path across a stone leaves a trace.’ All my experiences and emotions have slowly settled in me and matured. I’ve taken a stab at daring to write. I only began in my thirties,” says Hinrikus, who by today has already published nine children’s books.

Astrid Lindgren was Hinrikus’ childhood favorite. “I’m afraid I’m unoriginal, but there’s no way I can get past her books. I was read The Six Bullerby Children quite a lot and Little Tjorven, Kalle Blomkvist, and others are among my favorites. Books by other authors included Winnie the Pooh, [Eno Raud’s] The Three Jolly Fellows, and a little later, [Aino Pervik’s] Arabella, the Pirate’s Daughter,” the writer lists.

It was only later that Hinrikus came across Tove Jansson’s Moomin series and The Summer Book, a novel for adults in which a grandmother and her grandchild discuss the world as they explore a small island in the Gulf of Finland. “Someone wrote that that book is about life itself, and can be read your whole life long. I hold Tove Jansson in very high regard.”

Quality instead of glossy pictures

Hinrikus acknowledges that the children’s books and literature currently being published have changed over time. Not long ago, an avalanche of translated glossy-paged picture books were being released in Estonia and the world of Disney was storming bookstores, but today, original Estonian children’s literature is a very rich and diverse field. Writers are also taking on increasingly difficult topics. “Authors have become bolder. I hope that the children and teachers are, too,” Hinrikus says. “I think it’s great when children can take hope and support from a book; when they start to perceive the variations in the world and the fact that truths and values are different.”

The author says the Harry Potter series’ exceptional popularity shows that children’s interests have changed over the decades. “It’s a remarkably important book. I can’t compare it to a single one from my own childhood. Although fairy tales have always been around, kids these days are seemingly fascinated by more fantasy, mysticism, and alternate realities than before. I was fonder, personally, of more realistic types of books.”

Hinrikus derives her ideas from life itself and has been inspired by other books on many occasions. “Your own mind starts drifting towards new ideas when you read an interesting book – something additional to what you hear and encounter in everyday life. For me, writing isn’t toil and struggle; I thoroughly enjoy it. When I write, then I do so intensely. The rest of the time, I’m on standby and collecting my thoughts.”

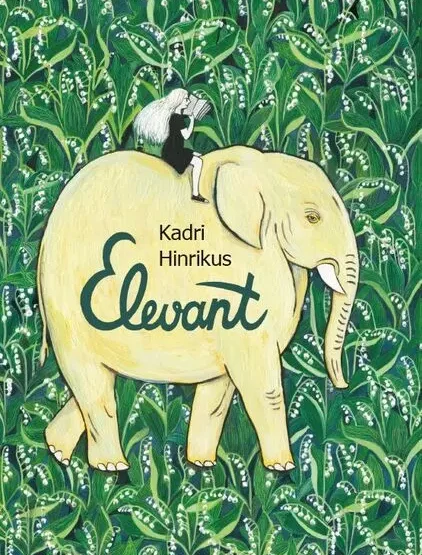

In addition to text, the illustration side of children’s books is very important. An impressive eight different illustrators have done artwork for Hinrikus’ nine books (only Anu Kalm worked on two). According to the author, every one of them has been fantastic, performing their art masterfully and with deep focus. Whereas words and illustrations form simultaneously in the case of some children’s books, Hinrikus always completes her writing first.

Writing for children is far from as easy, as one might believe, because attracting and maintaining a child’s attention is a fine art form these days. Every element of a book – the design, illustrations, sentence lengths, font size, etc. – must work together to better captivate the reader. “You have to keep in mind that the reader is much smaller than you. You can’t write for them like you would for your grandmother,” Hinrikus says. Although she has her own control group for testing out new books, one composed of both students and relatives, Hinrikus trusts her intuition above all. “If something is nagging at me, then I have to keep working on it. However, when I’ve wrapped something up, then my intuition tells me that, too.”

Hinrikus says there are many positive aspects of Estonian society, but there are still quite a few things that could be improved: friendliness, tolerance, and respect for different opinions are lacking foremost. “There are so many people who believe they and they alone have a monopoly over truth. Everyone who thinks differently are rotten to the core and are doing everything wrong. People could behave more based on what Uku Masing once said: ‘being good is what’s most important. Everything proceeds from the way we treat people, animals, and nature.’”

A mood of peace-making with the world

Hinrikus says one can’t rule out the possibility that Estonians’ darker side is encoded in their genes. “Of course we’re depressing compared with more southern peoples. Let’s all read [Andrus Kivirähk’s] November and look ourselves in the eyes. Estonians have complex personalities, and the long Soviet period certainly wore people out. It left us with bitterness and fears that some other nations escaped. There’s especially a lot of bitterness. And we place an exhausting emphasis on success. It’s like we’ve developed a cult of success that we instill in children at an early age, too. It’s a never-ending race and endless comparison of ourselves with one another. It seems like for many people, success and happiness are synonyms. In reality, though, I don’t believe it’s so straightforward.”

Hinrikus ventures into nature whenever possible, whether to hike in the woods or go sailing. “I don’t have the urge to leave Estonia for anywhere in summer, and in spring, I always want to see the birds arriving and the grass turning green. The season when the hackberry trees, chestnut trees, apple trees, lilacs, and rowans start to blossom is amazing. Their scents alone put you in the mood to make peace with the world.”

In the author’s opinion, people could learn to better enjoy what already exists. “In Estonia, life is beautiful and pure, both out in nature and in the cities. There are so many beautiful people; there’s so much good literature, music, and art. Estonians cook fantastic food. We’re able to speak in the Estonian language. It’s worth feeling delighted by all this and appreciating it. If we don’t do it ourselves, then no one else will do it for us. You can complain and find fault with everything to the bitter end. It’s worth seeing what’s good,” Hinrikus believes.

* Article first published in Eesti Päevaleht on April 28, 2018

Kristi Helme (b. 1979) directs the cultural desk of the daily newspaper Eesti Päevaleht. In addition to cultural life, she keeps a close eye on developments in Estonian education.