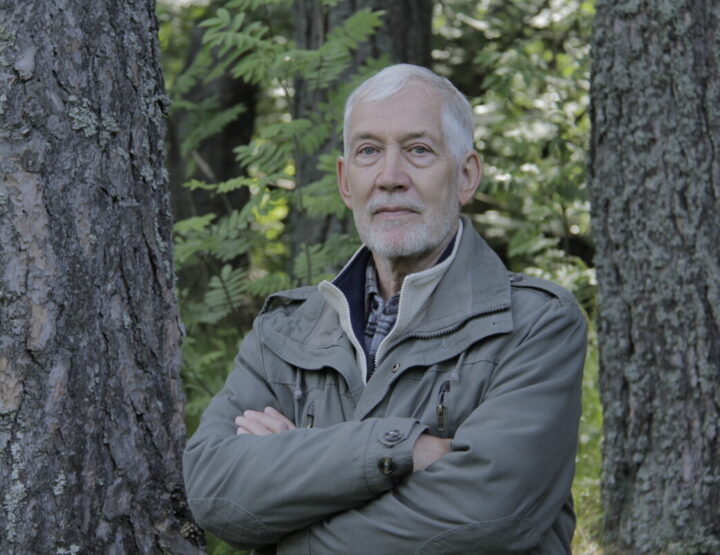

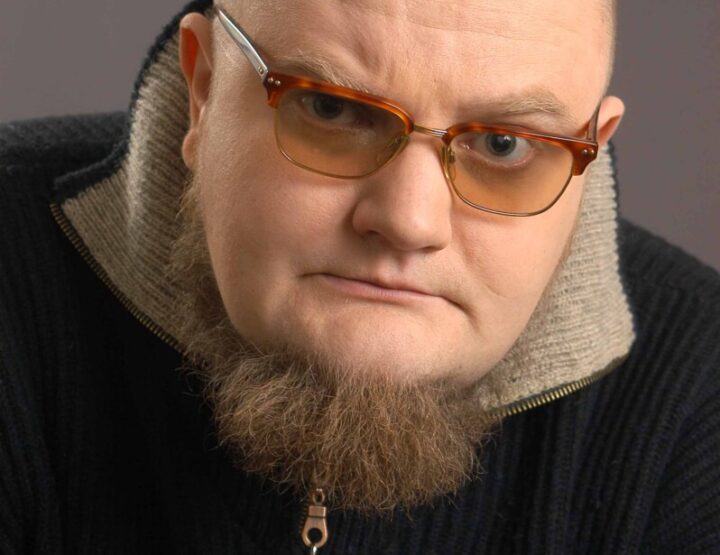

Karl Martin Sinijärv (b. 1971) made his debut in Estonian literature with the poetry collection Threecircle in 1989. Silvia Urgas’s debut in the Estonian Population Registry was made in 1992, and her own first work was the poetry collection Destination, published in 2016. At ELM’s request, Urgas asked Sinijärv what was on his mind, and he inquired if there was anything she’d like to get off her chest in turn.

SU asks, KMS answers

Your first poetry collection was published in 1989, 31 years ago. A friend told me that you can only write poetry until the age of 30, and the thought has plagued me. By that standard, your first book would already be too old to write its own poems. That argument is obviously false – take you, for example – but how would you explain that to the person?

It’s true that you can write a young person’s poetry until about the age of 30. Still, adult poetry and old person’s poetry don’t have to be all that bad. Things can get comical when you do your damnedest to write the same kind of stuff as that which brought you fame and fortune in your earlier years. It’s even more comical when you start rewriting the bold new speech you created back in the day. There are more than enough instances of both.

How do you feel that writing has changed for you over the course of your life? Do poems come to you differently than they used to?

I can’t say that writing has changed. In technical terms, yes – rarely do I write anything longer than my signature by hand. Most of the time, I don’t even have paper or a pen on me. But I’m always carrying my phone, so I can send myself an e-mail on the spot. The first thing I did when I was putting together my latest manuscript was look back through the e-mails I’d received from myself – they mostly contained poems or the beginnings of them. I suppose that, more often than not, I can’t really be bothered to write down undeveloped poems. Some marinate in the back of my mind for a while and whichever way I write them down is generally the way they stay.

Have there ever been moments where you think – that’s it, I’ve had enough of writing? How do you get through them?

Of course there have been. You get them with any addiction. Longer breaks, too. And giving up as well. Actually, by now, I’ve had it all the time. Right up until I feel like I have something to say again. Or a way to say it.

Your poetry and collections seem to have some kind of a cipher or secret code known only to you. For instance, there are a lot of numbers in your titles, like 28, 39, and 0671. Are they coordinates leading to some kind of hidden treasure or the (subconscious) development of an individual mythology?

Well, that’s easy. Some numbers ended up in the titles by pure chance through certain words (Threecircle, Shadow and Five-Pointed Star, Four Hundred Languages). Towntown & 28 included a longer poetic cycle and 28 other poem-like pieces. The same logic led to Artutart & 39. Then, I realized the only numbers I hadn’t used before in titles were 1, 6, 7, and 0. They would have resembled a meaningless year for me in that order, though, so I mixed them up and got 0671. A lot of people have thought I was conveying the month and year in which I was born, though I myself never came across it.

Have you written poetry in any language other than Estonian? Can an Estonian properly translate Estonian-language poetry or should someone hoping to make it big abroad just leave the Estonian step out entirely?

Writing in other languages is a great trick for learning them – if you even know just a little bit, then go ahead and write.The likelihood of you producing poetry that’s on any respectable level is near zero, but you’ll certainly become more intimate with the language. Translating poetry is basically rewriting it or making something entirely new. So, if you end up finding a translator whose sense for the language harmonizes with yours, then anything is possible. Otherwise, there’s not much of a point in translating it just for fun.

You’ve written poetry about many places – cities and streets – and have named people explicitly. Over the last few years, however, I haven’t noticed poets readily naming their friends in their writing. If they do, then they usually compare themselves to others, and not always in a positive tone. Is the camaraderie gone from Estonian poetry? And are Estonian poets destined to only write about Tallinn and Tartu?

On the whole, poems are grounded in the moment they are born and I suppose the mind is gripped by the given places, people, and foods at that point in time. It’s entirely possible that the inclusion of all sorts of relationships has declined a little in personal literature, who knows. I certainly don’t agree that Estonians only write things that revolve around Tallinn and Tartu. Still, it’s no wonder that those topics stick out more, given that the majority of writers live in those cities.

Have you always had a “day job” alongside writing poetry? Is doing something other than writing a constant limitation or actually inspiring?

I know of very few poets around the world who can get by on poetry alone. So, I’ve also held several different jobs over the last 30 years to make ends meet. It hasn’t been boring. And it certainly hasn’t gotten in the way of writing poetry or limiting anything. It simply means I haven’t written any works of prose. I only want to write the kinds of things that I myself would readily read, too. That demands time and concentration. Maybe my stipulations for a good book have gotten too high?

How does a poem by Karl Martin Sinijärv come about in the year 2020? How does it come to you or you to it?

Like always. An idea gradually starts to dawn and glow and take shape in my mind and at some point, when I feel it’s ready, I write it down. And they are ready, for the most part. Some of them do fade and never make it to the written stage, of course. Every now and then a practically finished piece suddenly appears out of nowhere – those are truly happy moments. So, I suppose words are able to line themselves up in secret without an author’s direct intervention.

Could you make a cultural recommendation? It could be a book, movie, TV series, song, or even your best culinary experience.

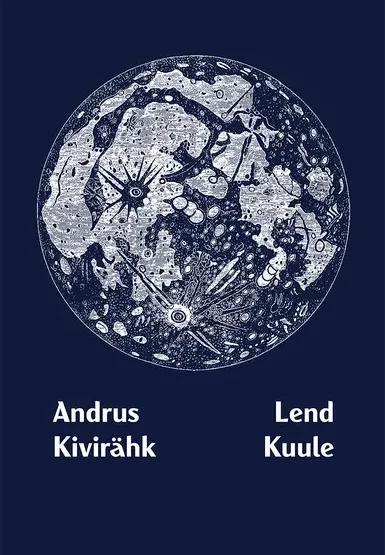

As for Estonian prose that has spread somewhat in translation, I’d recommend two series: Indrek Hargla’s The Apothecary Melchior books, seven of which have been published to date, and Paavo Matsin’s five novels starting from Doctor Schwartz through Congo Tango. In terms of newer cinema, I’d say The Old Man Film, which is a well-produced universal slapstick comedy. Music – I like everything that Erki Pärnoja is involved in and the new ethno-rock band Black Bread Gone Mad. My food recommendation is to find the potato salad that suits you best and don’t forget the recipe.

KMS asks, SU answers

You write densely but not frequently. At least, you’re not the type of author who churns out several collections a year or tosses everything you write into every platform possible as soon as it’s written. When can we expect your next book?

I generally try to write when I have something to say. At the moment, there are more ideas than I can manage, and as a result I jump between different documents on my laptop without finishing any of them. It’s definitely not a method I’d recommend to anyone in any field, but I hope I’ll be able to clean up my chaos in the near future and hopefully it’ll materialize as a book. I don’t release everything I write immediately, most of it ages for a while before anyone else sees it.

Once, someone who had published a book with a friend cheerfully called themselves a writer in a newspaper article, and it stood out to me. At first, I thought: look at how the title of “author” has devalued. But then, I realized it’s actually a highly prized status if people so dearly wish to adorn themselves in a writer’s feathers. To what extent do you feel yourself a writer and how much do you feel like someone or something else?

When I graduated from university and realized that I couldn’t call myself a student anymore, at least for a while, then my world collapsed for a bit. Being a student is such a great calling through which to define yourself. I don’t often dare to call myself a lawyer as it seems like too big of a word, though I am one, in fact. It’s also led to situations where people think I’m a secretary at work. It’s the same with calling myself a writer, even though I’ve occasionally had to say it. In reality, I enjoy multitasking – having different roles in life (within reason) and not having to choose just one through which you can express yourself.

You’ve dealt a lot with copyright law in your education and as a lawyer. How does it seem to you at this point in time – is the copyright system in Estonia fine or is it outdated and more of a bother? Does it inhibit the free dissemination of the written word? We’re likely to see some kinds of changes in the coming decades.

It’s certainly not a bother, but Estonian copyright law dearly needs to be revamped and brought into line with the 21st century. Until then, it appears that real life makes adjustments just fine. In terms of the world and music, for instance, the issue of piracy improved dramatically with streaming fees and the illegal sampling problem was countered by moderately priced sample banks. All kinds of questions that involve monetary compensation like renting and the so-called Estonian “empty-cassette” fees are waiting for a miracle, of course, but I think it’s a broader global problem where wealth is collected in the hands of just a few people and organizations.

How is Estonian literature doing, according to your taste and judgement? The number of people who natively speak and write in Estonia doesn’t even add up to the population of a smaller district of a larger city, but regardless, we’ve had something bubbling here for quite a long time. Do you find it interesting here?

There are so many good books published every year in Estonia that I’d never manage to read them all in my lifetime, but it’s unnerving to look at the bookstore sales charts and the more popular poetry groups on social media. First of all because of myself – I wonder if I really can’t understand what’s going on anymore – and second of all because of others. I wonder – can people really like all of that stuff? After I get all worked up, I have to calm myself down with the knowledge that taste is subjective and to each their own. It’s good to know that there do exist small community bookstores like Puänt in Tallinn and literary magazines like Värske Rõhk, but generally, it feels like there have been both much more interesting and boring times in Estonian literature than right now.

I don’t especially like to talk about influences and influencers, but I’ll just ask: what do you particularly like or are intrigued by in Estonia and/or world literature? And what’s particularly boring? What don’t you read at all?

At the moment, I’m reading Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels, which are so thrilling that I feel physically sick when I finish one and don’t have the next immediately on hand. My favorite Estonian author over the last few years has been Tammsaare. I read all of his books for the first time just a year and a half ago, and his goodness kind of gave me a little shock. My biggest find in terms of poetry lately has been the Macedonian author Nikola Madžirov. I try not to read any stiff or artificial books, nor art for art’s sake, but I won’t turn down any genre or style.

I could ask the same about world affairs – what floats your boat and what doesn’t particularly sit well with you?

I sometimes feel like I’m just swept along with everyone’s arguments in the big news stories, though I’m also deeply worried about the environment and the climate, and loathe many of the recent political developments in Estonia and around the world. Still, I’m already exhausted by the ridiculousness happening everywhere, so lately I’ve been falling behind the news cycle on purpose and am enjoying blissful procrastinated ignorance. I’d like to say that everything interests me, but I’m not a big fan of professional sports. Except for European football every two years.

Do you like cooking, and if so, then what?

I enjoy cooking, but only when I don’t have to serve the food to anyone other than me. I get too stressed when cooking for someone else, especially because my favorite food is pasta with cheese and tomato, seasoned with a pinch of salt, and people generally think that if you’re older than ten, then that kind of gastronomy is a little sad. I can happily make precisely two dishes for other people: beet risotto and vegan potato salad.

Are you happy?

What a question to end with so over-dramatically! Since I’m bad at small-talk, I’ll say honestly that I’m more so than not on the whole, though I’m definitely not satisfied with everything about myself or my life. Still, if I were to make a list of the people, opportunities, and fortunate twists I’ve been given, I can only answer that I am. Compared to these, the little misfortunes my own head feeds me are completely trivial.