The revolving-stage concept, first used in a Munich theater in the late 19th century, can certainly be a metaphor to describe the 21st-century Estonian literary field. By “literary field”, I mean the network of ties that connect authors, publishers, books, readers, and literature’s status in society.

I’ll attempt to elaborate on the revolving-stage metaphor. One immediate justification for its application is the outstanding importance of theater in Estonian culture, starting from the 1870s when the romantic nationalist poet and journalist Lydia Koidula (1843–1886) laid the foundations with the Vanemuine singing and acting society and ending with the nearly 20 professional theaters and dozens of project-based theaters active in Estonia today. In summer, it’s hard to find an Estonian city, town, or other suitable rural landscape without a play or musical being performed. As Estonian theaters put on nearly 7,000 performances attended by close to 1.2 million people in 2022 alone (for comparison, Estonia’s current population is 1.3 million), there’s not a shred of doubt that out of the cultural “trinity” which can be used to describe Estonian preferences—literature, choral singing, and theater—the latter is the most prominent.

Thus, the revolving stage, which allows quick, smooth transitions between scenes and characters, is a particularly vivid symbol of contemporary Estonian literature if you compare the early decades of the 21st century to its earlier development. The process has been a sporadic sequence of revolutions that have begun with manifestos, clearly definable generational transitions, aesthetic or political ideologies, interruptions, and rebirths. Hasso Krull (b. 1964), one of today’s most renowned Estonian poets and philosophers, has described Estonian culture as one of interruption and its literature as a conglomerate of multiple sub-literatures. Tiit Hennoste (b. 1953), another authoritative linguist and literary academic, has described Estonian literature’s hectic 20th-century course as “a leap towards modernity”. He has also controversially called the “Europeanization” of Estonian literature a mark of self-colonization.

Here, I will list the most significant ruptures of 20th-century Estonian literature and their central authors, now regarded as classics. The century began with the establishment of the Young Estonia literary group in 1905. Guided by poet Gustav Suits’s (1883–1956) slogan, “Let us be Estonians but become Europeans”, the movement was a true tour de force that transformed not only our notion of elite culture and aesthetics in literature, language use, and visual art, but put it into practice in the form of albums, journals, public performances, and publishing.

One illustrative example includes the activities of Johannes Aavik (1880–1973)—a future linguist, critic, and translator called a “linguistic revolutionary”. For Aavik, the expressiveness of the Estonian language wasn’t merely a question of literature but Estonian culture as a whole. Friedebert Tuglas (1886–1971), who founded the Estonian Writers’ Union (1922) and its literary magazine Looming (1923), was another main Estonian literary ideologist. Tuglas was responsible for starting the genres of Estonian short stories and literary essays. The Siuru literary group continued the early-century Sturm und Drang [Rl1] [Rl2] practiced earlier in several genres by Juhan Liiv (1864–1913), an existentialist patriotic poet, and Eduard Vilde (1865–1933), Estonia’s first professional writer – with volcanic performances. Siuru endowed Estonian literature with an immortal icon in the form of the poet Marie Under (1883–1980), though Henrik Visnapuu (1890–1952) also shaped the language’s poetic directions.

The novels by Anton H. Tammsaare (1878–1940), who began writing in the days of Young Estonia, achieved monumental status in the 1920s and 30s, especially due to his Truth and Justice pentalogy (1926–1933). Prose’s victory march justifies labelling that decade as the first epic era of Estonian literature. By the end of the period, a generation educated in the independent Republic of Estonia had come of age with the literary scholar and translator Ants Oras (1900–1982) at its forefront. His poetry anthology Arbujad (1936) lent its name to a creative group that focused on uncompromising intellectualism and sprouted into an entire galaxy of future literary classics such as Betti Alver (1906–1989), Heiti Talvik (1904–1947), Kersti Merilaas (1913–1986), and August Sang (1914–1969).

Estonia’s occupation by the Soviet Russian regime in 1940 split the already mighty tree of Estonian literature. Most of the works written between 1920–1940 were locked away in the cellars of special archives and many writers who remained in Estonia faced a similar fate of imprisonment or deportation to Siberia. Estonians who escaped to the West as refugees organized a diaspora literary scene in the 1950s and 60s, the leading figures of which were Bernard Kangro (1910–1994), Kalju Lepik (1931–2017), and Karl Ristikivi (1912–1977). The most latter of which was seen as Tammsaare’s successor with novels he wrote in the late 1930s. For several decades, Estonian literature written in the West and within the Soviet empire became the most important platform for resistance.

The next literary breakthrough took place in the 1960s, driven by the free-verse poetry and broadened horizons of Jaan Kross (1920–2007), Ain Kaalep (1926–2020), and Ellen Niit (1928–2016).

A “cassette generation” followed from 1962–1967: poets who made their debuts with booklets packed together in small cardboard boxes. Iconic authors from this period who enriched Estonia’s literary modernism and discovered new passages include Paul-Eerik Rummo (b. 1942), Hando Runnel (b. 1938), Jaan Kaplinski (1941–2021), Mats Traat (1936–2022), Andres Ehin (1940–2011), and Viivi Luik (b. 1946). Two outstanding exceptions from the period were Artur Alliksaar (1923–1966), a linguistic virtuoso who survived the Gulag, and Juhan Viiding (Jüri Üdi, 1948–1995), an outstandingly talented poet and actor.

Noteworthy and prolific prosaists who began their journey in that period include Arvo Valton (b. 1935) and Enn Vetemaa (1936–2017). Viivi Luik, Jaan Kaplinski (1941-2021), and Ene Mihkelson (1944–2017) began their careers with poetry but moved on to write influential essays and prose. Mats Traat’s 12-part South Estonian family saga Minge üles mägedele (Go Up into the Hills, 1979–2010) spans the mid-19th to the mid-20th century and is comparable to Tammsaare’s Truth and Justice.

Jaan Kross undeniably became Estonia’s epic literary landmark during the 1970s. His four-part historical work Between Three Plagues (1970–1980), which follows the life of the 16th-century (allegedly) Estonian chronicler and pastor Balthasar Russow (1536(?)–1600), explores a core topic of Estonian literature: the price and collateral paid by a small nation for its existence alongside large nations and states. Kross’s autobiographical novel Treading Air (1998) also addresses the subject in an artistic and documentary manner. Kross, who was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature on at least five occasions (especially after his internationally renowned novel The Czar’s Madman was published in 1978), indeed planted autobiographical elements in all his works, including his “school novel” The Wikman Boys (1988), which is set in Kross’s alma mater Jakob Westholm Gymnasium. His ethos echoes in the words of Director Wikman: “And I wish to tell you this: we Estonians are so few that every man’s goal, or at least the goal of every Wikman boy, must be immortality.”

Estonia’s independence was restored on August 20th, 1991. Metaphorically, what marked the beginning of the century was repeated: a “storm and stress” into Europe; accession into European institutions; feverish transition into a market economy and the rapid accumulation of capital; entrepreneurism’s injection into the free media, book publishing, and other artistic production. An entertainment industry established itself in the country and most culture became a consumer product. The market share of time-wasting literature and self-help books exploded. The post-modernist view of life and art blurred the lines between seemingly classical value hierarchies (i.e. literature’s role in the creation of national identity) and interpretative templates.

Even so, what appeared to be another accelerating change only ended up affecting culture’s outermost surface and the accumulation of all types of artifacts. Märt Väljataga (b. 1965)—one of the most influential 20th– and early-21st-century Estonian literary ideologists and editor-in-chief of the avantgarde journal Vikerkaar—stated at the dawn of postmodernism’s ascendant decade that “what is termed ‘postmodernism’ only forms through the cooperation of cultural institutions (universities, magazines, critique, etc.)”, yet at the same time, the narratives that bind Estonian society together remain vigorous and do not dissolve into postmodernity itself. The creation of the Cultural Endowment of Estonia in 1994 also contributed greatly to national vitality, smoothing out some of the effects wreaked by market forces in the creative sector. It was shortly after midnight on September 21st of that same year the ferry Estonia capsized in one of the greatest disasters to occur on the Baltic Sea. I believe that poet, translator, and professor Jüri Talvet’s (b. 1945) poem “Elegy to the Estonia”—written shortly after the catastrophe—serves as a literary counterpoint to the 1990s, reminding us of the frailty of humans and nations even in the greatest state of freedom.

The first two decades of 21st-century Estonian literature have resembled a revolving stage with ever-increasing clarity. New digital platforms and the recent discovery of the possibilities of artificial intelligence are making writing and publishing available to all. Never before has the number of organized writers been so great in Estonia: the Estonian Writers’ Union had 336 members by its centenary in 2022. At the same time, writing is growing more niche in terms of genre and audience, i.e. crime novels, memoirs, science fiction, esoterica, LGBT literature, and the traditional genres. The discussion of nationality or any human grouping is being made increasingly difficult by the fracturing and blurring of the cultural scene as a whole. Amidst the revolving stage’s kaleidoscopic diversity, the creation and preservation of identity through fundamental codes—something that was regarded as literary culture’s primary function—is losing its meaning.

Recent years have brought extraordinary abundance to the Estonian cultural scene, including the literary field. The full annual list of original works published by the dozens of Estonian publishers totals an average of 3,500. However, print runs appear to be declining: a couple hundred copies in the case of poetry collections and fewer than a thousand copies of novels. The large proportion of children’s writers is one welcome aspect of today’s literary field, while the abundance of high-quality translations also shows the field’s maturity. In the spotlight at the front of this revolving stage are Andrus Kivirähk (b. 1970; best-selling work November, 2000), Tõnu Õnnepalu (b. 1962; Border State, 1993), and Indrek Hargla (b. 1970; the now eight-part Apothecary Melchior historical crime series).

Vahur Afanasjev (1979–2021) contributed a new epic to contemporary Estonian literature with Serafima and Bogdan (2017), set on the shores of Lake Peipus. Noteworthy modern poets include Doris Kareva (b. 1958), who has achieved the status of a living classic, and Triin Soomets (b. 1969). Jürgen Rooste (b. 1979) has left a striking mark with his socially critical poems. Every two years, the Estonian Writers’ Union holds a novel-writing competition that generates dynamic new fiction (Serafima and Bogdan won in 2017). Armin Kõomägi (b. 1969), who has won the Friedebert Tuglas Award for Short Stories twice, took first place in the 2015 competition with his apocalyptic novel Lui Vuton. Estonia can also boast a fantastic writer of magical realism: Mehis Heinsaar (b. 1973), whose outstanding collections include The Old-Men Snatcher (2001) and The Chronicles of Mr. Paul (2011). Urmas Vadi (b. 1977) has occupied a unique literary niche with his original style, and Kaur Riismaa (b. 1986), who practices several genres, stands out with his polished writing that brims with dreamlike transitions and allegories (The Blind Man’s Gardens, 2015, and Snow in Livonia, 2022).

Another aspect of the revolving stage is the fact that the 1960s generation is packing up its earlier works and heading to the back alongside writers who are now mere historical figures. Starlight can also penetrate that periphery, however, as demonstrated by Paul-Eerik Rummo and his play It Rains Stones All the Time (2015), an “anachronistic capriccio” based on Jaan Kross’s historical short story “Skystone” (1975); Jaak Jõerüüt (b. 1947) with his confessional diary-novel Variable (2017); and Viivi Luik with her documentary novel The Golden Crown (2023), which depicts life as a magical crossword puzzle and won the Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Award for Literature.

Although neither authors nor revolving-stage literature possess the same authority in Estonian society as they enjoyed in the 1980s, the fate of Estonian literature in the 21st century will be decided not at the desks and computers of writers so much as it will be in schools, libraries, and every family that still engages in reading and finds the necessary time for it. Every book is in a state of suspended animation until it finds its audience—a process of eternal resurrection.

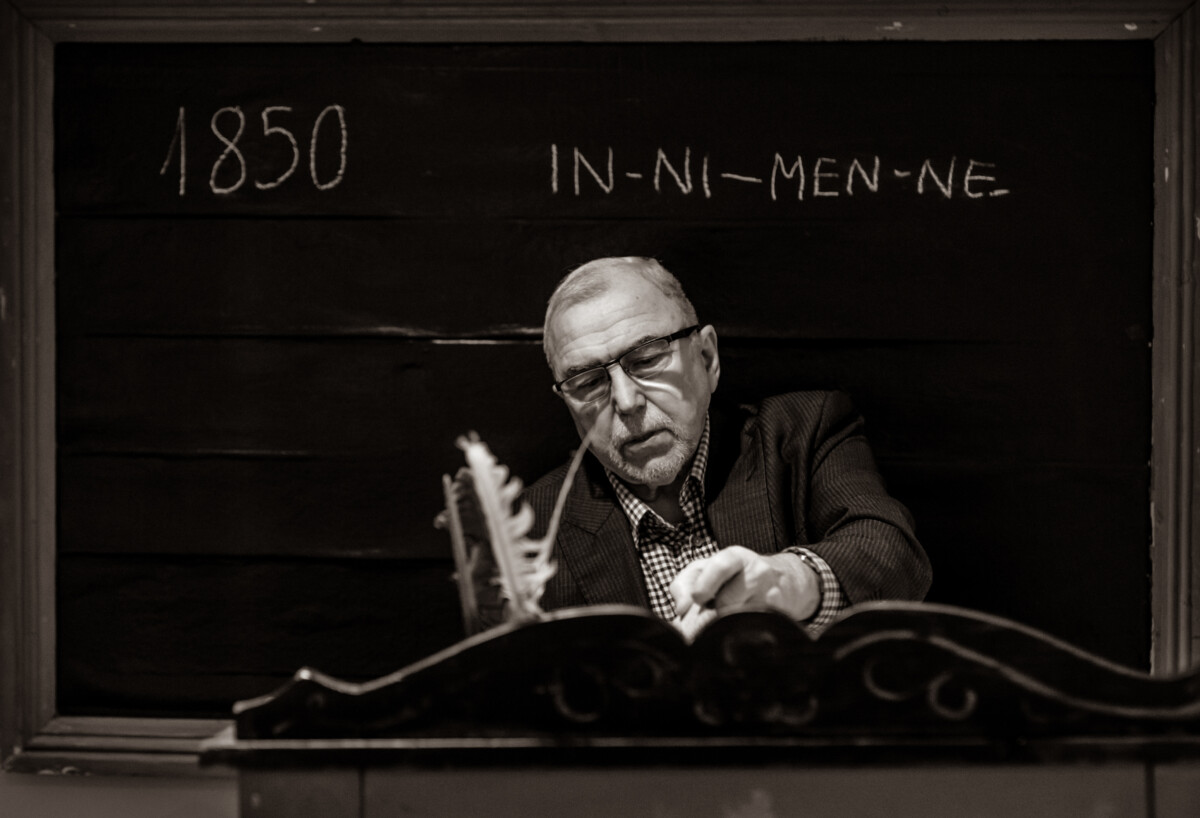

Rein Veidemann (b. 1946) is a literary scholar, cultural essayist, writer, and professor emeritus at Tallinn University. He also taught Estonian literature and culture at the University of Tartu from 2001 to 2005. Veidemann has published over twenty works, primarily collections of articles and essays, five novels, and one poetry collection.