Estonian Literary Magazine was first published in 1995 and has served as a window into Estonia for those who do not speak Estonian but wish to acquaint themselves with its world and its literary scene. For nearly 30 years, ELM kept a watchful eye on developments in Estonian literature, carefully selecting authors and texts for translation and introduction and striving to convey important contemporary developments. Thus, ELM’s history is simultaneously a history of Estonian literature’s path out into the world.

Of course, Estonian literature in 2024 is no longer what it was in the mid-90s when ELM began. Nevertheless, one can say that contemporary literature’s main trends were set in place during those early years. ELM was born amidst rapid changes and in a decade that Estonian sociologist and politician Marju Lauristin called our “return to the Western world”[1]. Just as Estonian society turned its gaze to the West and strove to regain its rightful place among the countries of Europe, so did Estonian literature seek outlets and readers outside of its own linguistic space and former Soviet territories.

The world revealed by the fall of the Berlin Wall and the opening of Eastern Europe excited Western Europe in the 90s. History was being born right before our eyes and readers wanted to find out more. The first issues of ELM, which appeared in newspaper format, tried to capture this transformational moment and convey it to the English-language reader.

In ELM’s 50th issue, Estonian publisher and translator Krista Kaer recalled that era of opening and changes: “Foreign publishers sensed new opportunities—yet-undiscovered masterpieces could be hiding somewhere in the Baltic states, or authors there might presently be writing books that struck to the heart of that turbulent zeitgeist!”[2]

One of the aims behind ELM was to inform foreign publishers of what was new and exciting in Estonian literature. Of course, its mission was broader: to introduce Estonian literature to an audience of literary enthusiasts around the world. ELM was distributed through Estonian embassies, sent to foreign libraries, and found its way to the mailboxes of loyal and dedicated subscribers.

ELM also became crucial in teaching Estonian literature to non-Estonian students. For more than a dozen years, I’ve taught Estonian literature in English at Tallinn University to students from an array of countries, extending from Japan and the US to India and Germany. ELM has been a fantastic tool thanks to its translated excerpts, lengthy articles, interviews, and summaries of new Estonian fiction, poetry, and children’s literature. The magazine helped university students stay informed about the Estonian literary scene.

ELM’s early issues reveal what was important in Estonian literature at the time and what was believed to be of interest beyond the newly reestablished national borders. It’s noteworthy that the first issue also contained a translation of Kristjan Jaak Peterson’s prophetic 1818 poem “The Moon”: “Cannot then the tongue of this land / on the winds of song / raised to the heavens / reach its own eternity?” (translated by Eric Dickens). The poem has long been a symbol of the Estonian language’s vitality, and its inclusion in ELM’s very first issue was intended to show that the Estonian language and literature possess an even greater might, that both the language and literature could spread throughout the world through translations.

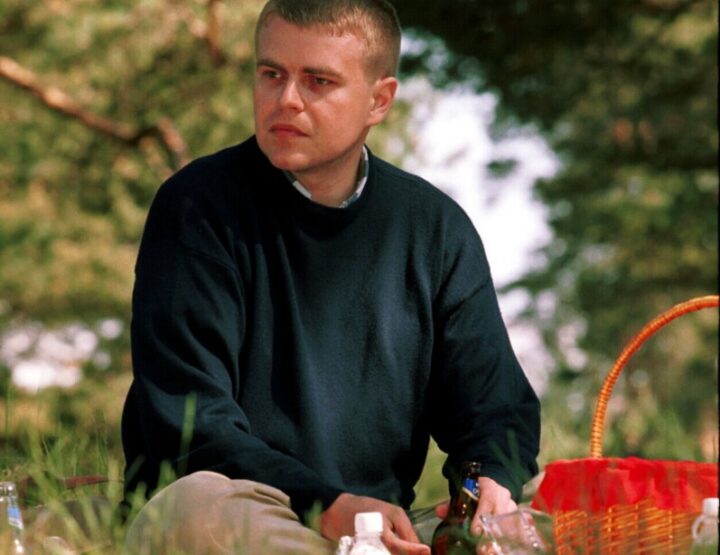

ELM’s first issues contained essential overviews of Estonian literary history composed by Mati Sirkel and Hasso Krull and reviews of poetry, children’s literature, and drama. Estonia’s most-translated work in the 1990s was Border State by Emil Tode (Tõnu Õnnepalu), so it comes as no surprise that the very first ELM contained both a synopsis and an excerpt of the novel, the magazine also covered Õnnepalu’s later books regularly.

Looking through ELM’s early years, it’s clear that many central authors and phenomena of the 90s literary transformation were immediately conveyed to readers. Articles were published on ethno-futurism, (:) Kivisildnik’s unconventional poetry, Jüri Ehlvest’s novels, and Peeter Sauter’s writing. Biographies and translations of already-established authors were also included: Hando Runnel, Jaan Kaplinski, Andres Ehin, and Juhan Viiding, to name a few. Space was naturally left for bygone years with articles on the earliest days of Estonian writing and classics such as Juhan Liiv, Oskar Luts, and A. H. Tammsaare.

In this way, ELM endeavored to give readers new to Estonian literature a general historical background while simultaneously focusing on fresh authors and the aspects that make up the fabric of the contemporary scene in all its motley brilliance.

This continued in every issue that went to press. Estonian literature changed and developed over those years, and its most thrilling authors and trends all found their way into the publication. Flipping through the 57 issues, one understands its manner of development from the perspective of ELM’s editors, who sought phenomena that would pique the interest of non-Estonian readers while still conveying active literary trends.

ELM maintained a practical and professional view of Estonian literature. Its editors, advisory board, and authors were trustworthy. ELM helped Estonian literature find its way into the world. This journey was supported by the Estonian Literature Center since 2001 and, since 2000, the Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Traducta Program, which provides funding for translating and publishing Estonian literature in other languages. Thanks to this professional diversity and cooperation between multiple institutions, Estonian literature is better known worldwide than ever, with increased annual translation figures and the heightened visibility of Estonian authors on the international stage.

The Estonian Literary Magazine was crucial in making Estonian literature visible far afield from Estonia. We will never know all the individual instances, though it’s possible that after a quick browse at an Estonian embassy somewhere, a guest may have headed straight to a library the following day to borrow a translated work of Jaan Kross, Tõnu Õnnepalu or Andrus Kivirähk. An Erasmus student in Tallinn may discover the poetry of Elo Viiding or Tõnis Vilu in a copy of ELM and be so moved that they buy Estonian books and begin to explore the mysterious and unfamiliar language. Perhaps they will one day become a translator of Estonian literature themselves.

Thus, the Estonian Literary Magazine has been an essential window into that world for those looking through it with purpose and interest and for those who casually glance at its pages. Although this window is now closing, it will hopefully reopen in another form so that Estonian literature’s global journey may continue just as successfully as it has.

Piret Viires (b. 1963) is a literary scholar and professor of Estonian literature and literary theory at Tallinn University. Together with Krista Kaer, she edited the first issue of Estonian Literary Magazine and has been a member of its advisory board since its beginning. Viires is also the vice-chair of the Estonian Writers’ Union and a board member of the Estonian Literary Center.

[1] Marju Lauristin et al. (editors), Return to the Western World: Cultural and Political Perspectives on the Estonian Post-Communist Transition, Tartu: Tartu University Press, 1997

[2] Krista Kaer, “A Path a Quarter-Century Long”. Estonian Literary Magazine 2020, No. 1, p. 2