I – Discovering the Regi Song

There was once a boy growing up in the Estonian diaspora who watched too much television. He stopped watching television in 1978 and has not owned one since then – what a release and sense of freedom! One of the programmes he used to watch was a situation comedy called ‘The Farmer’s Daughter.’ Although not the most memorable of series, it nevertheless, for some strange quirk, always remained in his mind. He can’t remember any of the situations or other characters except the farmer’s daughter herself. It never occurred to him at that time why he should remember this programme so clearly. But what does this have to do with my discovery of the regi song? I will return to the farmer’s daughter very shortly, however before I do…

Many of the readers of this journal will undoubtedly know about the regi song, but for those who might not, let me digress and mention, in a few words, what it is: the regi song constitutes the oldest extant layer of Estonian culture; it is a type of song and style of singing that goes back at least a couple of thousands of years and has, surprisingly, survived the millennia – in certain areas of Estonia it’s still a living tradition to this day. Some observers might contend that the regi song is the only genuinely original aspect of Estonian culture.

Very simply: the regi song generally consists of four-foot trochaic lines of verse exhibiting alliteration and parallelism. The following song, which my first true love sang to me years ago, is an excellent example of all the basic features of the regi song text:

Laula, laula, suu-ukene, Sing now, sing now, li-ips, so dear,

liigu, linnukeelekene, Stir now, song bird’s sweet tongue, so dear,

mõlgu, marjameelekene, Mull now, berry-spirit, so dear,

ilutse, südamekene! Joyful be my heart now, so dear!

Küll sa siis saad vaita olla, Surely then a-silent you’ll fall,

kui saad alla musta mulla, When you’re ’neath the blackest good earth,

valge laudade vahele, In between those boards of whiteness,

kena kirstu keske’elle! In the inside of a sweet chest.

Note that I have adjusted the transcription of the word suu (mouth, lips) a bit (from suu to suu-u) – this is merely to indicate that the word is sung as two syllables; I have also done the same in my translation, where I have split lips over two syllables. I don’t think I need to point out the eight syllables of the four-foot trochaic lines or the examples of alliteration (in the Estonian text) and the parallelism – the attentive readers are sure to spot these for themselves. The regi song is usually sung to melodies with a very narrow range of notes; each line of verse is usually sung by a lead singer(s), and then the chorus repeats the same line as an unbroken chain of singing.

Now, before I return to the farmer’s daughter, let me share with you the first time I was exposed to the regi song – it was like one’s first experience with sex; you never forget it. It was one summer in the 1970s; I was spending the weekend with some local expatriate Estonian friends, and someone had managed to get a tape of an LP record called Kadriko by Collage, a jazz ensemble quite popular in Estonia at that time. When I heard that tape for the first time, I was mesmerised – completely – by the melodies, the words, the rhythms – it was as if a whole new world had suddenly been opened up for me. Collage had taken regi songs and tunes and presented them in a slightly ‘jzzed-up’ version, but the songs on this LP were essentially regi songs. That night I borrowed the tape and listened to it over and over again. My favourite piece was Venna sõja lugu (The Brother’s War Story) – not least because of its pacifist message, and I am, if nothing else, a pacifist. I have not been able to get that song out of my head. That was my first experience of the regi song! I suppose I’ve been addicted to these songs ever since.

In the latter half of the 1970s I went to study at Helsinki University in Finland. I was a student there for a number of years. Among other things, I studied folklore and found my way into the Finnish collections of regi songs – the Finns refer to these same songs either as runo songs or Kalevala-type songs, but it’s the same tradition as the Estonian regi song.

While in Finland I also discovered an author by the name of Hella Wuolijoki. She was a well-known Finnish playwright and at one point she had collaborated with Bertolt Brecht who, incidentally, was a favourite playwright of mine. It turned out that Wuolijoki was an Estonian expatriate in Finland in the early part of the previous century and that she had prepared an index to Jakob Hurt’s collections of the Estonian songs. From this work, and based on the variants of the song ‘The Brother’s War Story’, she compiled a long poem of her own in the regi song style, Sõja laul (The Song of War). Parts of this were used by Brecht in his play Der kaukasische Kreidekreis (The Caucasian Chalk Circle).

Now, why did I start this story with the farmer’s daughter? Well, in 1937 Wuolijoki wrote a play, Juurakon Hulda (also referred to as Parlamentin tytär (The Daughter of the Parliament)), which was published under the pseudonym of Juhani Tervapää. This was made into a film in Finland, which was later picked up by the Hollywood movie moguls and in 1947 turned into a film called – can you guess – The Farmer’s Daughter, staring Loretta Young and Joseph Cotten. This film later, in the early 1960s was the inspiration for the series that I, – yes, I was that boy – that I used to watch. So, here’s the interesting coincidence/connection; the Farmer’s Daughter, with no connection whatsoever to regi song, but, which for whatever reason, stayed in my mind, came out of the work of Hella Wuolijoki, who was directly connected with one of the songs that first carried me to the world of the regi song. I have no idea whether this is merely a coincidence or some sign from above, but it is, nevertheless, an interesting…coincidence.

While in Helsinki in the late 1970s and early 1980s, I continued my discovery of the regi song: in the libraries, archives, museums, bookstores. By this time of course, contact between Estonia and us in the expatriate communities of the diaspora had been resumed; it had been quietly going on for quite some time already – it was still far from having becoming normalized. I started now acquiring materials on regi songs from Estonia, in the form of recordings, collections, commentaries, and scholarly publications.

The Helsinki days also saw my first tentative forays into the world of translating. In the short summer months I would take my notebooks, dictionaries and pencils/pens to the beach, where I toyed with different literary texts, dreaming about future projects: about creating the definitive English translation of a significant piece of Estonian literature. The dreams of youth! Well, perhaps those dreams weren’t so outlandish, after all. Over the years I have, in fact, managed to become a translator and have been involved in quite a number of major projects, several of which have involved the translating of regi songs.

Now, before I actually describe my work, the joys and problems associated with it and some of the projects I have worked on, it might be useful to repeat a few words about why translation work of this sort is important. It may be apocryphal, or something like this might really have happened, but after the end of the Soviet occupation of Estonia in the early 1990’s, when Estonian political and business people were trying to find support in the outside world, at some meeting with big business concerns, the Estonians were earnestly describing the past injustices perpetrated to them in hopes of justifying support. The mighty moneymen, however, looked at the Estonians and said something apparently to the effect that: ‘too bad, so sad…but what is it concretely, tangibly, that Estonia can offer the world’. I don’t think this is a point that can be belaboured too much – We Estonians can beat our chests as much as we want; we can talk about our misfortunes, we can gloat over the millions of lines of folklore texts that constitute our heritage, that we have achieved this, that or the other thing, but if we cannot offer the world something concrete then all our chest-beating will be to no avail. We have the resources – the expatriate communities around the globe can do one huge service for Estonian culture – translate it into major languages and help distribute it.

But let’s get back to regi song. In 1970 a collection of recordings were released under the Soviet Мелодия label, Eesti rahvalaule ja pillilugusid (Estonian Folk-Songs and Instrumental Music). This was a collection that all of us interested in regi song coveted but only few in the diaspora were able to acquire. I was lucky enough to get it through my contacts and friends at the Research Library of the Estonian Academy of Sciences. This collection was passed around, clandestinely copied, and used for learning songs – Tampere’s five-volume collection, Eesti rahvalule viisidega (Estonian Folk-Songs with Melodies) was a similar treasure for us. I often used many of the songs from both the anthology of LP records as well as Tampere’s books for singing at parties and other social events. However, since often there were non-Estonians at these events, it was always useful to have translations of the texts handy. Here I started to actually polish up some of the things that I had carelessly scribbled while relaxing on the Helsinki beaches. Usually, the translations that I passed around at these events were in prose, but if there was enough time I enjoyed providing versions in translation that were metrical and could actually be sung to the regi tunes. I recall at one of these events someone came up with the idea that the whole collection of songs from the LP records should be translated and re-released – of course, there was the huge question of who would re-release it – there was no question, however, as to who should do the translations. That idea didn’t get much further at that time. However, I continued translating the songs and putting them away for future use – just for fun!

Time moved on – Estonia managed to chuck the shackles of occupation; technology developed; and I merely kept adding to my collections. I also found myself performing more and more regi songs both in North America as well as at folklore events in Estonia and Latvia. As it turns out, I have sung regi songs in as far-away places as Mari-El, Udmurtia, Komi Mu, Siberia, and even Australia and India. So, I imagine I must have acquired some prominence in this area. And one fine day the good people in the folklore section of the Literary Museum in Tartu contacted me to inquire whether I would be interested in preparing a scholarly translation for the anthology of Estonian folk-songs (the same one originally released in 1970) that was going to be re-released as three CD’s. Of course I jumped at this opportunity – after all, I already had a goodly part of the work completed. After the completion of this set of CD’s, one of the people who has been instrumental in propagating Estonian regi song in earnest for decades – I’m speaking about Veljo Tormis here – heard me speaking about my translation work on the Estonian radio. He contacted me, and together we have worked on translating not only many of the regi songs that he has arranged for choirs but other songs as well. It’s been exciting, challenging and rewarding work.

II – Translating the Regi Song

But, now let’s look at things in more concrete detail: above in the beginning I described the basic characteristics of regi song: four-foot trochaic lines with alliteration and parallelism. Now, it turns out that almost like sub-atomic particles, whose velocity and position cannot be simultaneously measured – you either know where the particle is, or how fast it goes, but never both bits of information – so too with regi song – well, almost – it’s very difficult to translate the content, metre and alliteration all in the same version – parallelism seems to come out by itself – if we get the content right, then metre and alliteration is lost, if we get the metre then the meaning can suffer, but in trying to capture the original alliteration usually the meaning and metre both will be destroyed. The following two translations of mine for the song, Petis peiu (Swindler Swain), illustrate quite nicely what I mean here. Below is the original song: translation A appeared in the scholarly CD anthology and is a literal translation of the original; the parallel translation B is one I prepared for Veljo Tormis, and follows the poetic metre. The reader can compare the two; in a scholarly edition, quite rightly, the first one is the only one we can use, while in terms of poetry and artistry the second one is better; and clearly, for the translator, the second version offers more satisfaction.

Tule aga mulle tuisurille,

sulaselle suisurille,

pere- aga -pojale peiarille!

Perepoig on perguline,

petab palju, peksab palju,

valestab, varastab palju.

Lubas aga tuua kolmed kingad,

ühed puised, teised luised,

kolmandad kivised kingad –

puised kingad pulmakingad,

luised kingad lustikingad,

kivised kirikukingad –

ei saand pahu paslijagi,

vallast vanu viisujagi.

Translation A Translation B

Come to me, a madcap fool, Marry me now, I’m a mischief maker,

a reckless servant boy, loller farmhand, trickster, prankster,

a rogue of a farmer’s son! sure and I’m the son of a master jokester!

The farmer’s son is a devil, Swindler swain, a rogue and scoundrel,

he cheats a lot and beats a lot, cheats a lot and beats a lot and

lies and steals a lot. tells great lies then steals and pilfers.

He promised to bring me three pairs of shoes, Promised that he’d bring me many slippers,

one pair were to be wooden, the second bone, wooden slippers, boney slippers,

the third were to be stone shoes – grand ones they were stony slippers,

the wooden shoes were to be wedding shoes, wooden ones for when we marry,

the bone shoes were to be shoes for making merry, boney ones for making merry,

the stone shoes, church-going shoes – grand stone ones as Sunday slippers –

I did not get even a pair of worn mocassins, I didn’t get e’en old worn pattens,

or old bast shoes from the parish. nor a pair of birchbark bast shoes.

In the English translation for Tormis, the few examples of alliteration, for example, marry, mischief, maker in the first line, are actually quite fortuitous, and don’t appear in the original. Normally, alliteration would be difficult if not next to impossible to capture. The lines 10, 11 and 12 in the Estonian exhibit alliteration, and the choice of words in the original song is based on the first sound of each line’s key word. The original lines are:

…puukingad pulmakingad / luukingad lustikingad / kivised kirikukingad… (…wooden shoes as wedding shoes / the bone shoes as shoes for making merry / the stony shoes as church-going shoes…)

The key words in Estonian are: pulmakingad (wedding shoes), lustikingad (shoes for making merry) and kirikukingad (church-going shoes); the respective descriptive words are chosen according to the initial sound; puu (wooden), luu (boney) kivi (stony). I won’t even attempt a translation here that captures the alliteration, but just for fun, try it for yourself!

The alliteration and parallelism work together hand-in-hand and one seems to feed the other. The result is, in my opinion, one of the more artistic and magical achievements of this genre where a myriad of images and metaphors are created, sometimes quite fantastic ones. Jaan Undusk in a recent article suggests that what we have here in this aspect of the regi song is soul-magic in the most direct sense of the word.

The following song, again one that appears in the scholarly anthology, allows for a great deal of artistic creativity. It is a nonsense song that appears all across the Balto-Finnic continuum: versions of it are found in Estonia, Finland, Carelia and Ingria. It is presumed to be a translation of some German song, although, what the original German version may have been is unclear. However, it is not a translation in the usual sense, rather the songster has replaced the foreign German words of the original, which he or she probably didn’t understand in any case, with pseudo-words that are reminiscent of those in the original. The result is a wonderful piece of nonsense. I approached the translation in exactly the same way. I let the nonsense words in the Estonian version remind me of words and word stems in English. Then I came up with something that look like they might be English words and just created my own nonsense from that. It was great fun.

The title of the Estonian song is Onnimanni, which apparently is a corruption of a German word related to the English alderman, and so from that my title: Aulder-Maulder

Ui-sui-sui-sui sunnimanni, Oh so, so, so Saulder-maulder,

sunnimannist sain mallika, I got a cudgelcalf from the Saulder-maulder,

mallikast sain mannipilli, from the cudgelcalf I got a jennyjuble,

mannipillist sain peebuna, and from the jennyjuble I got a wryegg,

peebunast sain petsariini, from the wryegg I got some mockereanie,

petsariinist sain riimuka, from the mockereanie I got a rhymerie,

riimukast sain rindasõlge, from the rhymerie I got a breastbroachessie,

rindasõlesta sõmera, from the breastbroachessie some shingle-gravel,

sõmerast sain soolavakka, from the shingle-gravel I got a salt cellar,

soolavakast vaisiküisi, and from the salt cellar failinailies,

vaisiküisist kübara ja from the failinailies a brand new hat,

kübarast sain künniraud, from the hat I got a ploughing iron,

künnirauast sain ranitsa ja from the ploughing iron I got a knapsack,

ranitsa sain rapsuvitsa from the knapsack I got a beating twitch,

lapse puksu pihta peksa – to paddywhack the children’s fartybums –

raps, raps, raps, raps, raps! swat, swat, swat, swat, swat!

III – Celestial Suitors

While in Finland I realized that the regi song is a genre that is not restricted to Estonia alone. It is part of the very ancient common heritage of the Balto-Finnic peoples. Variants of the same songs, similar motifs and themes occur from across the territories of the Estonians, Finns, Carelians, and various smaller groups that once lived in Ingria, the Votes, Izhorians and Ingrian Finns. But a number of things began to trouble me: apart from the scholars who work very directly with the songs, most people, and in particular those with no ties to the Balto-Finnic world, seem to be unaware of this common heritage. Anthologies that are published either deal with only Finnish songs, or Estonian one, occasionally a collection of Carelian songs will appear and sometimes something about the songs of the Ingrian groups, but no collection looks at the regi song tradition as one that is common to all the indigenous peoples in these areas. A second problem exacerbating the situation is the label given to the tradition; the Estonians refer to it as the regi song, while the Finns refer to it as the runo song. In English sources the most common variants (and most usually in reference to the Finnish songs) are the terms runic song or Kalevala-type songs.

I don’t want to discuss the Estonian and Finnish labels here, however, I would like to comment briefly on the English terms. The term runic refers to the Scandinavian runes, archaic alphabetical letters used for writing Old Norse. By extension from its meaning of ‘archaic’ it has been extended to refer to the ancient songs of the Finns, even though runes as such, were not in common use in Balto-Finnic areas. The most accurate use of the term runic song, however, is in connection with ancient Scandinavian songs in which the various letters of the runic alphabet are enumerated, much like the English song for teaching children the notes of the scale, Doe, a deer, a female deer, and so on. Thus, this term is not a really adequate label for our songs. The second alternative, Kalevala-type song is, in my opinion, particularly lamentable. The problem with this term is that it would suggest the Kalevala has a certain primacy, which it in fact does not have. Not to denigrate the Kalevala – in fact, I think it’s a beautiful and unbelievably interesting work – but it is an artefact of 19th century nation building in Finland, and is based on a small number of the ancient songs that were still extant at that time. However, the consequence has been enormous. Kalevala has assumed a folkloric significance that it perhaps should not have. Because of the mistaken belief that the Kalevala is somehow a primary source, even the great Finnish collection of ancient folk-songs Suomen kansan vanhat runot (Ancient Songs of the Finnish People) is usually divided into two large sections; variants of the songs that were incorporated in the Kalevala, and all the other songs, of which there are possibly a great many more. Moreover, I have also attended conferences where scholars have suggested certain things about ancient Finnish culture based on what is found in the Kalevala, without having actually examined the original songs that were adapted by the compiler of the epic, Elias Lönnrot, for his literary opus. I would like to have an exact and unbiased label in English for referring to the ancient songs of the Balto-Finns. Otherwise, my feeling is that we should only use the very cumbersome expression: four-foot trochaic verse with alliteration and parallelism.

This brings me to another project that I have been working on for quite some time. The idea for it also occurred to me on the Helsinki beaches; namely, an anthology of the ancient songs of the Balto-Finnic peoples. I began the actual collecting of songs for this anthology quite a number of years ago. Now I have a clear idea of what it will look like. It will be called ‘Celestial Suitors’ and will be in two parts; the first part will consist of the narrative songs, those songs that tell some sort of story; the second part will consist of customary and lyrical songs, such as work songs, calendar songs, and emotive songs etc. All the songs in the anthology will be represented by several variants from different geographic regions of the whole Balto-Finnic area to show the similarities and differences in treatment of the same themes.

I have already selected the narrative songs, and with this, the first part of ‘Celestial Suitors’ is ready to enter its second phase, the translating phase. Below is one of the narrative songs that I have already translated. This is one of the variants from Kuusalu of the song describing the origin of the psaltery (kannel, kantele), that ubiquitous musical instrument known to all the Balto-Finnic peoples, as well as the other peoples on the eastern littoral of the Baltic Sea:

Ma laulin kiriko teela, I sang on the way to church,

kirikussa, karjamaala. in church, in the pasture.

Käliksed minogi tappid My in-laws killed me

suurela munakivila, with a large boulder,

täravala kirveella. with a sharp axe.

Kus nad viisid neio noore? Where did they take the young maiden?

Viisid kulla marja soosse. They took the gold one to the berry bog.

Mis sealt minusta kasvis? What grew out of me there?

Minust kasvis kallis kaske, A dear birch tree grew out of me,

ülenes metsa ilusa. a pretty forest rose up.

Mis sealt kasest tehtanekse? What are they making from the birch?

Kasest kannelt raiutakse, A psaltery is being hewn from the birch,

violida vestetasse. a violin is being carved.

Kust said lauad kandelale? Where were the boards got for the psaltery?

Löhe suure loualuusta, From the jawbones of a giant salmon,

hauvi pitka hambaasta. from the long teeth of a pike.

Kust said keeled kandelile? Where were the strings got for the psaltery?

Juuksest sai neio noore, From the hair of the young maiden,

karvast sai kodukanase. from the hairs of the hearth-hen.

Ei olnud pilli peksiada, There was no one to play the instrument,

kandeli elistajada. no one to ring out on the psaltery.

„Mino ella vennakene, “Oh, dear brother of mine,

vii kannel kamberie, take the psaltery to the chamber,

sea sängi sörva peäle, arrange it on the edge of the bed;

peksa ise peigelalla, beat it with your thumbs,

oska sörme otsadelle, know how to do it with your fingers tips,

rapsi rauda kämbelilla!” strum the irons with your hands.”

I have now started gathering the songs for the second part. Since this is a large undertaking that I am doing apart from my regular work, it is taking a long time, but when it is finished it will provide a more realistic picture of what the regi song is all about, and perhaps also what it is not.

IV – Kalevipoeg

Kalevipoeg like the Kalevala is an artefact of 19th century nation building. It was also complied, perhaps less so than the Finnish epic, from regi songs, but Kreutzwald poured the disparate elements that went into the making of this epic into essentially the regi song form. Over the years I have had occasion to speak about the Kalevipoeg and have translated a few short passages. The following is my verse translation of the Invocation to the epic:

Laena mulle kannelt, Vanemuine! Lend to me your psalt’ry, Vanemuine!

Kaunis lugu mõlgub meeles, In my mind there stirs a story,

Muistse põlve pärandusest legacy of distant ages

Ihkan laulu ilmutada. this I long to sing out yearning.

Ärgake, hallid muistsed hääled! Rise up now, ancient bygone voices!

Sõudke salasõnumida, Sail forth, secret words of witness,

Parema päevade pajatust tidings from more golden days, those long past

Armsamate aegade ilust! of the joys from ages more pleasant!

Tule sa, lauliktarga tütar! Come forth, songster-sage’s daughter!

Jõua Endla järve’esta! Stir yourself from Endla’s waters!

Pikalt ju hõbedases peeglis Long have you in that silver mirror

Siidihiukseid silitasid. combed your silken tresses flowing.

Võtkem tõe voli, vanad varjud! Let us take truth’s own right , ancient shadows!

Näitkem kadunud nägusid, Let us show long-dead visages,

Vahvate meeste ja nõidade, valiant of men’s and wise shamans’ too,

Kalevite käikisida! freeborn heroes’ deeds of brav’ry!

Lennakem lustil lõuna asse, Soar we now joyful southward ever,

Paari sammu põhja poole, twice our paces to the north now,

Kus neid kasve kanarbikus, where those shoots in heather ‘waken

Võsu õitseb võõral väljal! flower in those other acres!

Mis mina kodunurmelt noppind, What I have plucked from my own pasture,

Kaugelt võõral väljal künnud, ploughed from distant other acres;

Mis mulle toonud tuulehoogu, what have the wind-gusts wafted to me,

Lained lustil veeretanud; waves have merr’ly rolled toward me;

Mis mina kaua kaisus kannud, what I have cradled as I carried,

Põues peidussa pidanud, in my breast I have hidden ‘way,

Mis mina kaljul kotkapesas what I have high in nests of eagles

Ammust aega hellalt haudund: brooded long with tender caring:

Seda ma lauluna lõksutelen this is a song I now warble warmly

Võõraste kuulijate kõrva; into the ears of others listening;

Armsamad kevadised kaimud dearest of kinsmen from my springtime

Varisenud mulla alla, they have fallen to their barrows,

Kuhu mu lusti lõõritusi, whither my mirthful merry trilling,

Kurvastuse kukutusi, nor the sorrow in my singing,

Ihkava meele igatsusi all of the longing in my yearning

Koolja kuulmesse ei kosta. cannot reach to their dead hearing.

Üksinda, lindu, laulan ma lusti, I am now, lone bird, singing here joyful,

Kukun üksi kurba kägu, calling sadly, lonely cuckoo,

Häälitsen üksi igatsusi, voicing forth, lonely, my own yearnings

Kuni närtsin nurmedella. till I moulder in the meadows.

The reader might notice that in this section the metre is not strictly in the four-foot trochaic form. Kreutzwald, in fact, varies the metre, at times quite considerably. This, however, gives enough variety to an epic consisting of essentially 20,000 lines of poetry to prevent it from going stale.

Perhaps in connection with translating, I might mention a few things that often cause consternation for a translator. I have used parts of Kalevipoeg in translation workshops and have run across many interesting solutions to problems. Often beginning translators find wonderful words to use. Several examples comes to mind to illustrate this:

For the Estonian original magajate mälestuseks one translator offered the following suggestion: requiem for those who’re resting. The translation is lovely, the metre is correct, they even found a chance to get the alliteration in there, everything is dandy, except for one thing – can you spot it? The word requiem – lovely, poetic, emotive – Latin, Christian. Yes, this was the jarring element here – requiem is a Latin word very strongly associated with Christianity; as such it is totally out of place in an epic that is set in pre-Christian Estonia. The appropriateness of the cultural and semantic field of any word is crucial to the success of a translation.

Another translator once found a beautiful word to use, sward. This is an extremely interesting word, quite poetic and very literary. They used it as an equivalent for the Estonian muru (grass). What’s the problem here? Sward has the meaning of grass (among a few other things) – but it is archaic, terribly literary and understood probably by less than 5% of the educated population of the English-speaking world (or at least those that speak it natively, never mind those for whom it is a second acquired language). Muru, on the other hand, is a completely commonplace, everyday word in Estonian, one that everyone understands instantly. The point here is that one needs to consider the stylistic register of the words used to translate a text. Another interesting problem with the word sward in connection with Kalevipoeg is the fact that it is so close in pronunciation to the word ‘sword’ and given that a sword is one of the main characters in the epic, this could cause potential confusion for readers.

Finally, I should mention that I’m currently on the team at the Literary Museum preparing the late Triinu Kartus’ English translation of the Kalevipoeg for release some time next year. This has been a project that from start to finish has involved a great deal of time and energy, on the part of many individuals but in particular Triinu. It will be a tribute to her love and dedication when her hard work finally reaches fruition. This is a project that the Eesti Kultuurkapital (Cultural Endowment) and Estonian Ministry of Culture have very generously supported

The road has been long and rich for that boy who once watched too much television. It’s a long way from having visited a farmer’s daughter to a world of magic, rhythm, fantastic visions, music and joy that the regi song has revealed.

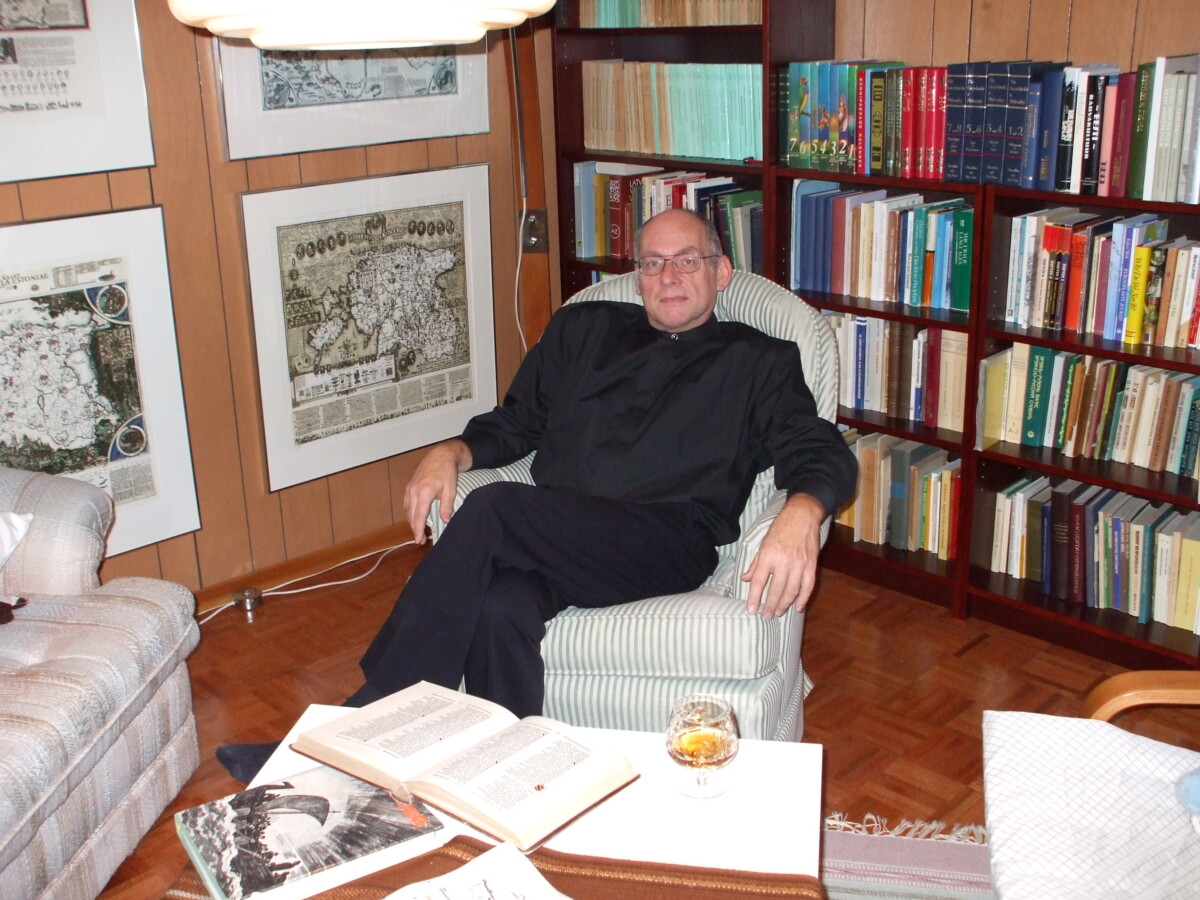

Harry (Harri) William Mürk

Born: June 1954, Canada

Education: B.A. University of Toronto (French linguistics and literature)

M.A. University of Toronto (General linguistics)

Approbatur Helsinki University (Finnish language and culture)

Ph.D. Indiana University (Uralic and Altaic studies)

Queens’ University (Information Sciences)