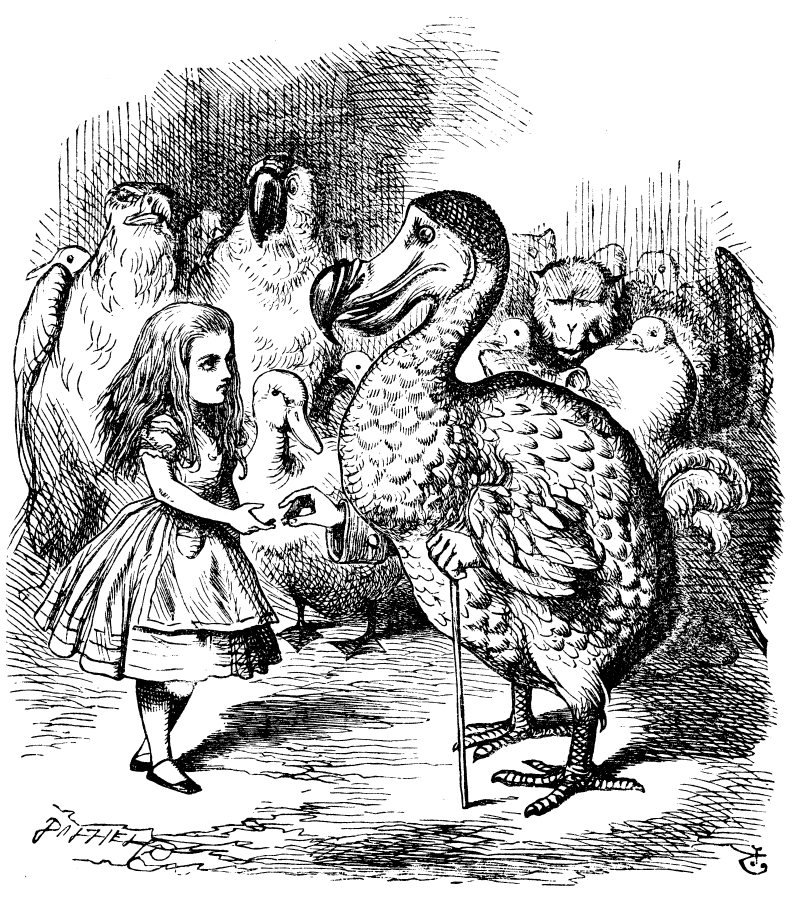

“Everybody has won and all must have prizes.”

Those are the Dodo’s words in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, and both James F. English[1] and Joel Best use them as an epigraph in their respective books. In English’s work, the handsome line is the epigraph for his first chapter “Prize Frenzy”; in Best’s, it is used for the whole book. The Dodo’s verdict (which probably doesn’t even need to be explained) is meant to illustrate the burgeoning of awards in today’s world.

Understandably, the number of awards isn’t the only thing that has swelled over the last fifty years. The global population and the economy have exploded (most of all the “unweighted” economy that includes the cultural industry), and the annual number of books published has increased along with people’s expenses on literature. Even so, the number of awards has increased with a sharper curve than anything else.

One particular curiosity that both English and, later, Best highlight is the fact that in the film world, there are twice as many awards as the number of full-length feature films produced each year. Anyone capable of producing something that doesn’t force the viewer to flee the auditorium in embarrassment can hope that somewhere there is a film festival where the film will be awarded, such as with a thematic, regional, or debut prize. Writers who have already received an award tend to believe there probably aren’t any unawarded writers left in the world, naturally forgetting their colleagues to whom the Dodo’s paradisiacal decision has not yet extended. Yet, even though the explosion of awards has not reached everyone, the numbers are still impressive.

English provides an overview of the growth of British literary awards: before World War II, there were hardly a dozen considerable awards, which came out to two or three per new book published. In 1981, there were already over 50 awards; by 1988, there were over 90; and by 2000, according to a modest estimation, there were at least 180 – though professionals in the book industry claim there were at least 400. The latter experts’ estimation was probably also highly modest or took into account only the larger awards, considering the population of the United Kingdom and how many literary awards there are per 100,000 residents of Estonia (the reader will find that data in just a moment). Leaving out the local and small-scale literary awards, there were over 1,100 in the United States by the turn of the century, which similarly seems like a very narrow count.

Best uses the growth of thriller awards as an example. In 1946, the “Edgar” genre award (named after Edgar Allan Poe) was issued for the first time; by the year 1980, there were already 25 crime awards, and by 2005, there were 99.

In 2014, the newspaper Main-Post claimed Germany had nearly 1,000 literary awards. That very same year, the international 50,000-euro Siegfried Lenz Preis was added to the mix. The renowned critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki is said to have complained about the inflation of literary recognitions already in 1962, even though there were only 120 such awards in Germany at the time.

Now that there are ten times as many awards, the Germans themselves are convinced there aren’t as many in any other European country. Several of them are prestigious and well-known: the Büchner Preis, the Kleist Preis, the Heine Preis, the Goethe Preis. The Germans’ international ambition in issuing these awards stands out in particular: they also issue a plethora of them to authors who do not write in German. Since 2017, they have also had the German Self-Publishing Prize (Deutscher Selfpublishing-Preis), although they are not alone in the field: in early 2017, Amazon also announced a £20,000 self-publishing award. I asked the poet Gian Mario Villalta about Italian awards: he reckoned they also have somewhere in the vicinity of one thousand literary awards, and that maybe even three awards are issued every day. His colleague Valerio Magrelli acknowledged this is probably the case, though he had the impression that, ever since he started writing, the awards of any importance have stayed the same: Strega, Campiello, Viareggio, Mondello. It’s difficult for new awards to achieve the same level of prestige; furthermore, they are primarily local.

It seems like the field of awards won’t be contracting any time soon. In the spring of 2018, the Estonian Writers’ Union Siuru Fund issued yet another new award: a grant for a young artist whose writing is “borne of the Siuru spirit”, whatever that’s supposed to mean. (Monetary awards are occasionally also called grants with the intention of emphasizing the recipients’ future hopes; naturally, not just any grant is an award). An award may also kick the bucket from time to time, which is a part of life. Two years ago, an article in The Guardian complained about the demise of several awards: one of the departed was the Hatchet Job of the Year, which recognized the most successful mean literary reviewer. The Germans issued their Chamisso Award for the last time in 2017, which was given to non-German authors of German-language books. The award had been criticized for promoting “Uncle Tom literature”, then watered down as foreign-laborer literature, though the fund justified its ultimate decision by saying the award had served its purpose. At the Transpoesie European poetry festival, the Belgian writer Peter Verhelst told me his country’s literary-award landscape has shrunk noticeably, and that several had withered away over the last few years. We drank wine at the BOZAR fine arts center in Brussels and were nearly running late to perform for a European audience; that was in October 2017. “It’s interesting you ask,” said Verhelst, who was proud his career wasn’t dependent upon grants.

Nevertheless, I don’t believe Belgium’s situation, as it appears to the poet right now, could be used to declare an overall shrinking trend. If I had to bet on either the expansion or contraction of awards around the globe, I wouldn’t doubt for a second.

More than murders

As you can see, there is, presently, a tremendous annual number of literary awardees in Estonia: as many as 75 during an especially bumper year, with a total of 258 nominees.

According to Statistics Estonia, Estonia had a population of 1,315,635 on January 1, 2017. If we assume there were indeed 258 nominees for literary prizes, we get 19.6 per 100,000 residents annually. If we reduce the number to a more modest figure and stay at 200 nominees, then the number comes out to a round 15 per 100,000 persons. Both are quite formidable figures.

Anyone wishing to compliment Estonia could mention in conversation that we have significantly fewer traffic deaths per 100,000 residents than we do literary-award nominees: over the period 2013–2016, for example, the average number of traffic deaths was 75 per year, which makes 5.7 per 100,000. By my calculation, there are almost the same number of laureates as there are road-accident victims every year, and if you add in the wide range of literary competitions and their second- and third places, there are even more. Of course, anyone can die in a car crash, but only someone who writes and is published (and that in a specific genre) can compete for a literary award. Still, it’s fun to imagine it as a game: you shake a big bag containing the names of Estonian residents marked with yearly events, pick one out, and it’s more probable you’ll randomly select someone who has been nominated for a literary award than someone awaiting a cruel fate on the highway.

There are also fewer intentional deaths annually in Estonia than nominees for literary awards; or, in fact, even fewer than the number of literary awards themselves. The number of police-registered first-degree murders declined sharply for at least a while: in 2012, for example, there were 63 murders, and only 52 in 2013. Let’s give the big bag of the population’s annual events a shake: leaving aside all other factors, it’s more likely a literary-award laureate will be picked than a murder victim.

On the other hand, there were 229 diagnosed cases of HIV in Estonia in 2016, which makes 17.4 per 100,000 residents and close to the same number of literary-award nominees. Unfortunately, we also tend to have a similar number of suicides: 18.9 per 100,000 residents according to 2015 World Health Organization data.

Furthermore, we have several dozen more inmates than literary-award nominees: a few years ago (in 2014), there were 238 per 100,000 residents. It’s even rarer to be a recognized writer than it is to be a convicted criminal. Things could be opposite in a perfect society.

More than wolves

How many writers are there in Estonia right now? Or how many Estonian writers are there? To determine this, one should firstly ask who the Estonian writer is in terms of either nationality or ethnicity, and the definition isn’t at all so simple. Is a writer someone who regards themselves as a writer? Or is a writer someone whom is outwardly labelled a writer, such as in a media channel? Say, for instance, “XY, a writer, shares her opinion about the draft domestic partnership law.” Who must be the one to say you’re a writer for you to be one? Is it your colleagues, other writers, first of all?

It’s obvious that the writer should have written and published something, but how much is necessary to be a writer and not simply the author of a couple specific pieces? How complicated, even irksome! The finance-based classification, i.e. “a writer is someone who makes a living off of writing”, is long since defunct in Estonia. Assuming, in the interests of simplicity, that a writer is someone who creates and publishes literature, and leaving aside the issues surrounding the definition of literature, let’s see how many such people reside in Estonia currently.

We will begin from the institutional level. As of September 1, 2017, the ever-growing Estonian Writers’ Union had 312 members, 176 of whom had published works of literature over the last five years, i.e. in the period 2012–2016 (thus, 56.4% of members were active literary authors at the given moment). These are individuals whose status as authors can no longer be judged institutionally. However, they are undoubtedly not the only authors in Estonia. The number of writers who had published literary works over the last five years was nearly three times as great; specifically, in the vicinity of 500. Consequently, there are certainly more writers living on Estonian territory than there are wolves, which numbered around 200 according to the latest estimate. At the same time, Estonia’s writers might even be equal in number to bears: about 700 in the year 2017. In the fall of that same year, a whopping 74 permits were issued to hunt and kill wolves in Estonia.

In his 2009 review of poetry for the Estonian literary journal Looming, Märt Väljataga wrote that when he compiled a similar overview for the same journal in 1987 with the author Hasso Krull, they had only 11 books of poetry to address; in 2009, however, there were 94 first-edition collections. As dramatic an increase as that was, in 2016 alone, there were 14 books of poetry published by authors who had already received or previously been nominated for a poetry award in their lifetime. That same year, more than 30 previously-awarded authors published works of prose.

Of course, there are many more awarded and active writers in Estonia than the 14 + 30 equation. If we add up the poets who are currently active (i.e. have published books recently) and have ever received an award, the total is somewhere near 45.

Additionally, if you include the active poets who have at least been nominated for awards, then we get well over fifty recognized poets – and here, I am only considering awards designated for poetry by adults.

I was able to tally already close to 70 active prose writers who have received at least one literary award (in addition to a horde of nominees). Some of the names of successful poets and prose writers overlap, but the plateau is broad and expansive overall: somewhere around 130 people (without counting young laureates without books). Thus, Estonia has its own basis point of recognized literary authors who write for adults: one ten-thousandth of the population. Perhaps one ten-thousandth doesn’t seem like all that great a share, but if we consider a similar ratio in a country such as the US, then there would be well over 30,000 awarded or nominated literary writers in that country. Such individuals would number 6,000 in Italy and 8,000 in Germany. One might doubt there are even enough tiny local awards or nominations to go around for so many writers in those countries, but who knows.

The fact that recognized authors form an entire basis point of the population would sit wonderfully with the Dodo. In the interests of fairness, however, I must confirm that those who feel Estonian literary awards are scant or that the craved podium is unjustly inaccessible are not uncommon, and it always happens that some fine work or author is left empty-handed at awards ceremonies. Additionally, one must take into account that not all awards are alike: their level of prestige differs. The more alleged experts on a jury (even when particular experts seem wrong), the more tantalizing the award. An award from a parish leader is nice, but let’s be honest. And we shouldn’t forget that recognition requires constant renewal: a win secured a long time ago may not feed a writer’s peace of mind anymore. Depending on the individual’s level of sensitivity, they might perceive themselves as nudged out of the picture if no new awards or nominations have been delivered, even over a period of three or four years. While one author may cocoon him- or herself in layers of recognition, the certificates remain fortuitous delights to others.

The above is an excerpt from Maarja Kangro’s new book My Prizes. An initial version of the text was published in the Estonian cultural weekly Sirp on March 16, 2018.

[1] James F. English’s book The Economy of Prestige. Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Cultural Value (2005) and Joel Best’s book Everyone’s a Winner. Life in Our Congratulatory Culture (2011).

Maarja Kangro is an Estonian poet, writer, librettist and translator. Her sharp and sensitive debut novel The Glass Child was published in 2016. She has also written several libretti for Estonian composers and has translated from Italian, English, German, and other languages.