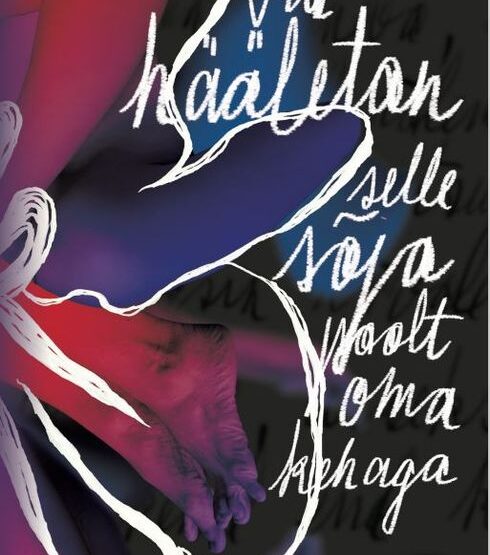

Sanna Kartau (b. 1993) is an Estonian poet and journalist whose debut collection I Vote for This War With My Body won the 2022 Betti Alver Award for Debut Poetry. That same year, she won the Värske Rõhk youth cultural magazine’s annual poetry prize.

Kartau, who lived for an extended time in Berlin, writes poetry that is influenced less by earlier Estonian verse than it is by Germany’s spoken word scene. Her poems often come to life only when read aloud or in one’s mind, their charm hidden in rhythm, not traditional form and style. In sharp contrast with regular Estonian poetry events – traditionally reserved, the authors preferring to tinker with texts in the silence of a study – she has brought with her an energy generated from organizing poetry workshops and returned a social aspect to the local craft that is uncommon in Estonia. Kartau co-edited an anthology based on materials created in her Berlin workshops, titled The Sundays Book. Her view that poetry need not be elite or inaccessible is put into practice via @mah22letan on Instagram, where she has made public every poem in her prize-winning debut.

In an interview given to Värske Rõhk in 2022, Kartau describes the jarring experience of moving back to Estonia: “My biggest culture shock is the deep loneliness that overwhelms me here sometimes. It’s a combination of just having been away for so long and the warmth that is an ethos ingrained in my Berlin community. There’s no comparable warmth-based community that’s fully established here just yet.” Since returning, Kartau has worked as the cultural editor of Müürileht, an Estonian newspaper focused on contemporary culture. Judging by her editorial in the December 2022 issue, she still appears to be captivated by that community to this day: “We get addicted to our nightly beers or a joint before work but, in the end, we still need, first and foremost, a sense of security, belonging, and recognition, and when those are guaranteed, then opportunities for self-development as well. We literally depend on one another, and I’m not talking about codependency […]. No, I mean the thousands of connections between people by which we receive confirmation of our own right to exist, both offering and accepting support.”

So far, Kartau’s writing hasn’t included socially critical manifestos or programs, but rather atmospheres and emotions that cannot be expressed in complete sentences. Themes throughout her poetry include childhood and family (“Mom’s heart awaits me in Vana-Antsla / at the wrong bus stop and doesn’t recognize me / or my buzz cut”), imposed work obligations (“when feverish me asks to go home sick / my boss tells me to show up for a later shift instead, / recommends I rest for four hours and get better. / – okay”), and searching for and finding community (“we all hugged each other, said thanks / conversations didn’t end and we stood in the doorway / too filled with excitement to put a sudden stop to the night / too many stories for sharing to fall silent / I studied my friends’ faces to commit that moment to memory”). As the collection’s title betrays, physicality also plays a significant role: “YOU who I reach my hands out to YOU / and share secrets with or from whose fingers / I lick cookie batter YOUR / just im- / possibly good black-pepper hair YOU on top of me / penetrating YOU when I’m hungry”.

Fortunately, Estonian literary critics’ superficial decades-persistent habit of dividing younger female authors into either delicate fairies practicing nature poetry or angry young women is diminishing. Although Kartau wrestles with her own thoughts on the femme/butch scale (“Sometimes it seems silly to love / what women love. Like gnawing / a poisonous bone.”), her writing primarily focuses on what it feels like to be human and how humanity is impossible without community.