Gunnar Neeme (1918–2005) lived most of his life in Australia and achieved international recognition as an artist. He published two Estonian-language poetry collections, three English-language collections, and wrote several plays. The posthumous publishing of his short-story collection Tuuleraudne (Windsure) could very well be the surprise of the year in Estonian literature.

Windsure comprises eight short stories that Karmen Maat, who compiled the book and wrote the foreword, has arranged into a coherent whole according to the author’s probable wishes. Underpinning the stories are events that Neeme no doubt experienced first-hand. Still, the work cannot be deemed autobiographical as such, as there are almost no references to any true figures, events, or settings. Neeme fought for Estonia’s freedom in the Second World War while wearing a foreign uniform, just as many of his compatriots were forced to do. His stories contain the voice of a generation that was patriotic but betrayed and exiled. Deft, delicately crafted, and full of pathos that expresses the absurdity of war—something that is all too relevant today—Neeme’s writing was clearly a way for him to work through wartime trauma.

The book’s title is both symbolic and polysemantic. It asks whether ‘windsure’ (Estonian ‘tuuleraudne’) is a destructive force of nature comparable to war, or the ability to resist and a reference to the divine altar to the narrating soldier once knelt before? Neeme’s style is polyphonic, self-argumentative, aphoristic, and paradoxical. A clear example of his intended contradictions can be found in one of his invented compound words: kääbushiiglane, or dwarf-giant. Anxiety and the horrors of war often echo in Neeme’s rushing, elliptical sentences that alternate with longer essayistic discourse. Contrasting civilization and a lifestyle in tune with nature, finding safety in memories of the forest and his time as a shepherd, Neeme—a hopeless romantic—remains a child of nature. He extolls nests and dens while juxtaposing them with artificial human houses, which are akin to prisons and set off a wicked chain reaction that only leads to destruction: street, city, machine, war. Moral pathos is self-evident in Neeme’s writing, but his inner voice and inner debates never produce unambiguous answers. Is a soldier a hero, a criminal, or something else entirely? Where is the line between freedom and anarchy? How should one understand the dizzying contrasts that appear in people’s lives during war?

The collection’s final story, “Closedness”, is a discourse on art philosophy that is paradoxical in and of itself as it focuses foremost on seeking openness. At the forefront are Neeme’s research and accomplishments in the field of visual art, to which the text is a worthy parallel. Just as in his art, the author creates powerful and vibrantly colorful literary images, the expressiveness of which alternates with a rich impressionistic palette. Exalting life and its diversity, Neeme writes that the singular is colorless, but plurality possesses a prism.

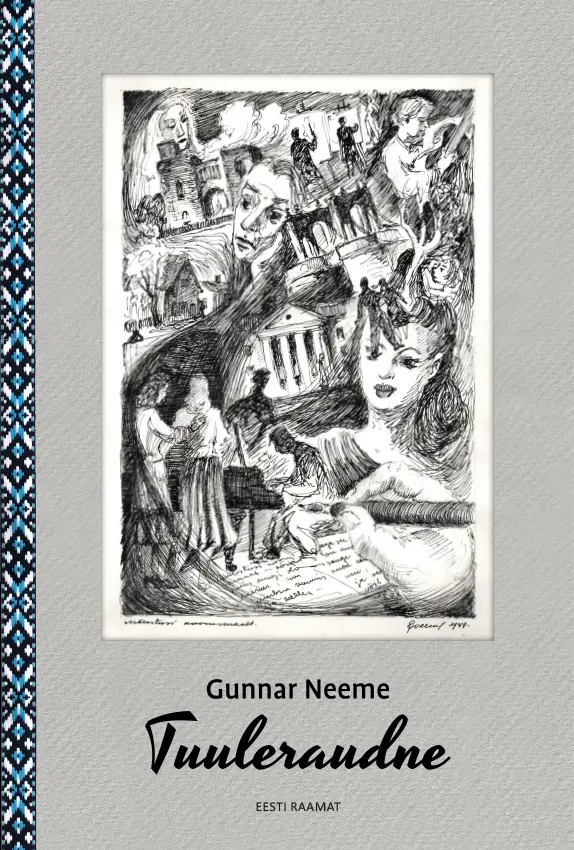

Unlike Neeme’s popular color-rich paintings, the book’s war-themed illustrations are strikingly black and white. Whereas his art generally doesn’t dwell on topics of war, his prose seems to yank readers into the heart of it. With potent idiosyncrasy, Windsure is a powerful word in humanist Estonian war prose.

Janika Kronberg (b. 1963) is an Estonian literary scientist and critic.

Gunnar Neeme

Windsure

Compiled by Karmen Maat

Eesti Raamat, 2023. 224 pp.

ISBN 978-9916-12-607-3 (print)

ISBN 978-9916-12-608-0 (e-pub)