Kaldmaa’s Lydia is the story of a little girl who grows up to become an esteemed poet. The author undertook the daring task of writing a childlike and educational book about the most revered female historical figure in Estonia: Lydia Koidula, born Lydia Emilie Florentine Jannsen (1843–1886), who is a symbol of the Estonian national awakening.

Before diving into the details, I can say that Kaldmaa’s goal is fully achieved – something confirmed by the 2022 Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Award for Children’s Literature.

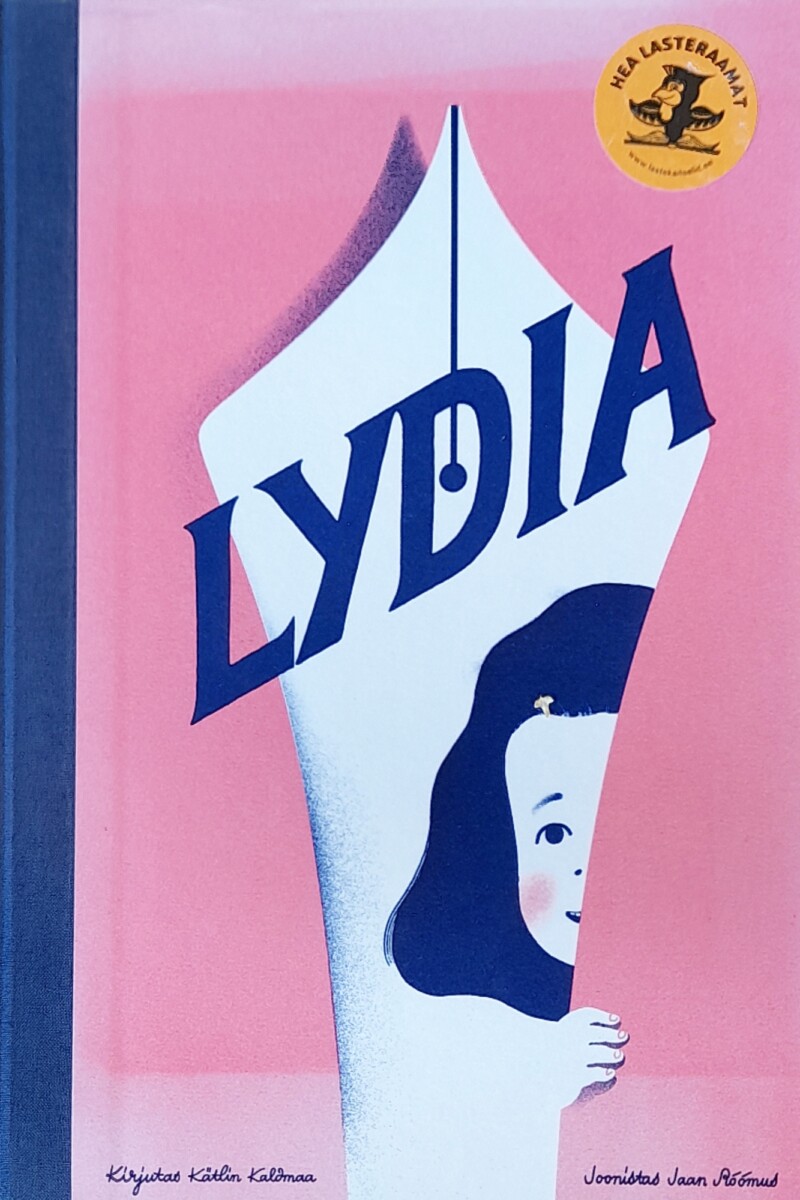

Much has been written about Koidula in Estonia, but mostly for an adult audience. Young schoolchildren, preschoolers especially, generally know very little about her. On the cover, young Koidula peers at the reader through heavy stage curtains. Opening the book is the same as opening a door to the past. But will a child identify with the message? To them, the word “past” sometimes equates to a fairy tale. Frozen’s Elsa is more recognizable and identifiable to them than Estonia’s first female poet. Kaldmaa signed herself up for a true challenge.

What’s more, Lydia’s youth coincides with tremendous changes throughout the entire world: the dawn of the Industrial Era. In the territory of Estonia, the peasant class gained greater equality in relation to the aristocracy, as did women to men. It is impossible to fit the historical background into a slender children’s book, though it isn’t meant to. It suffices for the author to occasionally reference the transformations: women aren’t yet allowed to publish under their own name, but educated persons are starting to affirm that Estonian, the peasant language, is as worthy as every other tongue. Here, the author brings up another legendary Estonian poet – Kristjan Jaak Peterson, who would have been a generation-and-a-half older than Koidula – and in doing so makes a purposeful anachronistic error: Peterson’s poetry was unknown in Koidula’s lifetime. But prose isn’t a history textbook. You can fib a little, compress, and add in the name of something good. A writer has the authority to emphasize whatever they wish.

For example, Lydia’s cover art references the fact that Koidula was also Estonia’s first original playwright, though the text makes no direct mention of it. Instead, Kaldmaa focuses on other significant moments in the writer’s life, all of which are critical points in Estonian cultural history. Her lifetime also includes the era of the first periodic Estonian-language newspaper and the first Song Festival. Lydia herself helps to found both in cooperation with another symbol of the Estonian national awakening: her father, Johann Voldemar Jannsen.

If we study the back cover carefully, we can see a quill – something few modern-day children will recognize. On the whole, Lydia presumes an older and wiser person is never far from the young reader. There are so many fascinating details that require explanations, such as a dated map with different names for the towns and cities Estonians know so well, poems written in archaic Estonian. Several cultural figures with difficult names, and a healthy dose of knowledge that doesn’t seem to fit with Lydia or poetry overall (though this is deceiving, as she was a very learned woman), including astronomy, Latin, and German, for starters. Kaldmaa brings up the head of the university and philosophy students. Someone will need to break down the complex sentence: “Intelligent, educated women aren’t looked upon well in society.” But the author isn’t at fault. On the contrary: her belief in a child’s ability to comprehend is praiseworthy. She invents connections, such as when Lydia sees a tiger lily and starts thinking about the tigers her father told her about. The protagonist thinks outside of the box, as children often do. Lydia preserves the child within and thanks to that, she grows up to be an exceptional woman.

The book is filled with love. The character’s mother and father gaze tenderly at their newborn daughter and try to come up with the loveliest names to give her. At a very young age, Lydia wishes to help her father with his difficult job as a newspaper editor. As a young woman, she teaches her Estonian pupils with love, sharing both knowledge and joy that is so great it inspires her to sing. As time goes by, she becomes a full-fledged adult and the best mother her two daughters could ever ask for – smiling, always willing to play, and glowing. You cannot love your native land if you do not love your family.

Lydia isn’t a feminist work, though it is a nice female-centric book that should also be suitable for boys. It is a book for all ages. I myself enjoyed it thoroughly.

Kaldmaa has composed a fantastic introduction to one piece of Estonian culture. It is writing that invites one to question and dig deeper, hopefully on both sides of the borders of Estonian language and culture. The ability to cross divides is stressed through Lydia’s life as well. Koidula and Jannsen were the first to begin forging cultural ties between kindred Estonia and Finland, which isn’t overlooked in Lydia.

The book’s design also deserves special mention. Jaan Rõõmus achieved a fantastic outcome with a modest palette of just red and blue. A newspaper headline, the copied page of an old poetry book in unusual type, and many more cultural treasures embedded in the illustrations make the story of Lydia and her native country more visible. Lydia concludes with Koidula’s portrait on the front of the 100-kroon banknote. Thanks to these design elements, and especially Kaldmaa’s fascinating style of writing, we realize that Koidula, Estonia, and poetry are all part of a greater cosmic world.

KÄTLIN KALDMAA

LYDIA

Illustrations by Jaan Rõõmus

Hung 2021, 44 pp.

ISBN 9789949731985