“I don’t write for children,” Maurice Sendak said. “I write and I’m told: ‘That’s for children.’” A few generations earlier, J. R. Tolkien asserted there is no such thing as “writing for children”, and even C. S. Lewis did not agree with regarding children as some kind of unusual breed of human. Despite statements like this and the richness and depth of important works of children’s literature, even today, one can encounter the attitude that children’s literature is the poor cousin of “adult” literature – a type of art that hasn’t achieved its developmental peak yet, and is therefore unworthy of the full attention of those who admire serious literature.

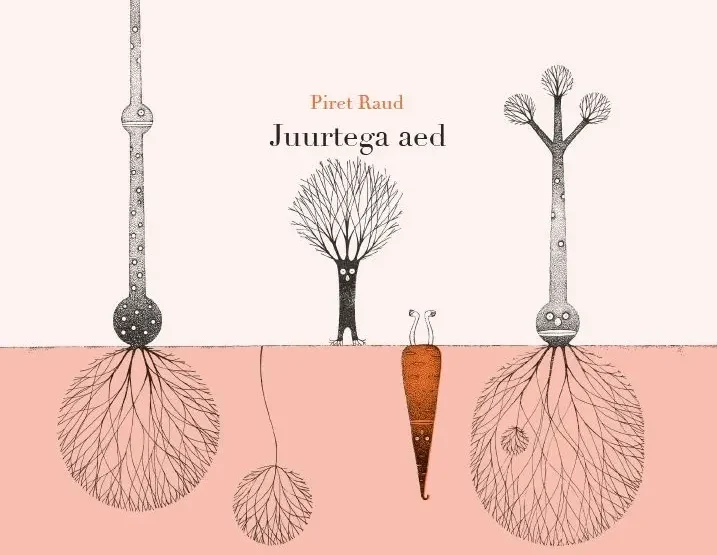

Last year alone, seven books by children’s writer and artist Piret Raud were published in languages not Estonian. Since 2009, her works have appeared as 24 works of translation in 12 different languages, which makes her the most-translated Estonian writer of recent years. We spoke with Raud about her journey through the world of art and writing to find out her opinions on illustration and literature made for children, as well as what she sees her role in that world to be.

In your opinion, is childhood a temporal concept that designates a certain period in a person’s life and must come to an end one day, or is it a condition in which you can exist, to which you can return over the course of your life, or which on some level actually lasts your entire life? Jacques Brel, for example, has said that for him, childhood is foremost a geographical concept – a place.

Childhood is one part of a person’s life. What comes to an end someday is life itself. A person changes over their entire lifetime, while at the same time always staying him- or herself; both as a child and as an adult. Childhood is a time when a person is just starting to get to know life – children possess fewer experiences, and that’s what sets them apart from an adult; as for other aspects, a child is a person just like all of us.

What is children’s literature, and who is a children’s writer? Is that kind of genre- and author designation important for you? Is it substantial?

I have no problem with children’s literature as a concept. I believe that when writing, a children’s writer should always consider his or her audience so that the outcome is understandable to the child. But speaking more generally, a distinction should be drawn between a children’s book and children’s literature. Not all children’s books are necessarily literature. A lot of educationally-oriented texts, or else product-like things that go along with a toy series or a film are written for children. When I write for children, I give thought to the pure technical details: the idea has to be clear, and I don’t use very complex sentence structures, either. I take a child’s reading ability into account, as well as the fact that they read more slowly than an adult, and so the pace of activity is relatively fast in my books. If I were to write for adults, I might pause and debate some idea or a topic at greater length or describe a situation. I consciously avoid that in a children’s book. My books definitely contain things that might easily go over a child’s head while reading – situations and scenes that he or she will have a completely different understanding of as an adult. I personally hope that my books have multiple layers; that they can be read on several strata. It’s important to me for a book to also touch a child on an emotional plane.

What kinds of ideas and feelings did you have when you started writing for children? Was it a conscious decision – I want to write for children and not for adults? Has it limited you, or on the contrary – has it had a liberating and enriching effect?

I wasn’t a writer at first; I didn’t choose the writer’s path at the beginning of my creative journey. I personally regard myself as more of an artist to this day. I started writing a while after beginning to illustrate. At one point, I felt I wanted to write the texts for my pictures myself; or, rather – I wanted to personally come up with the story and draw the pictures for it. At first, I did a lot of collaboration with my mother, Aino Pervik, who is a writer, and that went really well; but even so, at one point I felt that I wanted to try writing on my own. I was in awe of writing for a long time. To me, it seemed that everyone who writes writes very well, and that you have to have a great deal of talent and definitely also an education in linguistics in order to write. Even now, I sometimes wonder what kind of a linguist or writer I am… My parents Aino Pervik and Eno Raud both wrote for children, and both were linguists, too. My mother’s books are characterised by very rich and nuance-heavy language. I think that the language I personally use in my books is one that I acquired from home. I often give my texts to my mother to read – she is definitely a very unassuming critic, but even so, she gives me useful hints here and there. Some critics have indeed compared my books and style to Aino Pervik’s works and language. I didn’t like it at first, but then I started to think – maybe it is true that there’s a certain similarity to our texts. The language in which I write is, in fact, my mother tongue, we all acquire our language from our mothers, and therefore it’s natural for there to be similarities of speech and thought between our mothers and us.

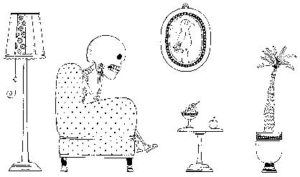

As for liberty as a writer and an artist – I feel that for me, there’s more freedom in pictures – in imagery – than there is in words. An image can talk about something that I can’t touch in words. When I address a grim topic, for example, I can use grim colours in a picture – I can even paint everything black. What I like about writing for children is that you can talk to them about complex things in a simple way, and that doesn’t have to mean simplification. I remember how when I was doing my master’s degree at the Estonian Academy of Arts, I thought about how in arts academia, people endeavour to talk about simple things in a complicated manner, and sometimes I also came up with how to say one thing or another more complexly, more academically, in a more “distinguished” way. The charm of children’s literature lies in the very fact that you can do the opposite. At the same time, the world of children’s literature isn’t predetermined as “bright” – in my opinion, you can write about anything for a child. Even so, there are topics that are taboo for me and I refrain from handling. In my works, I enjoy handling what I do in relatively pleasant tones. For me, sadness can go towards the positive side, too. Of course, I undergo all kinds of social upheavals – everything negative that goes on in society or foreign policy – but I don’t want to bring it with me into my work. At the same time, there are sad, melancholic, and also sharper moments in all of my children’s books.

You mentioned taboo topics in children’s literature – what are those for you?

Sexual self-gratification, torture, rape. Every one of my books has someone who is safe for a child; a supportive person. For instance, I wouldn’t like to portray a mother as a true deadbeat in any book. But death and illnesses aren’t taboo for me – they’re a natural part of life. There are children’s books in the world on the topics that are taboo for me, there are writers who write about those topics, and so I don’t necessarily have to. I haven’t kept a single book away from my own children, although it’s been the case that I give my child a book and later, when I read it for myself, I’m shocked at how cruel and bleak the world is that I sent my own child into.

You’ve illustrated the majority of the books you’ve written. How has being an artist and having started out as an artist affected you as a writer? You’ve said said something before to the effect that you’re an artist, but writing seems like nicer work. Why?

I like to imagine things, to create new worlds, and that happens in the field of writing. Drawing is more like craftwork. My family tells me that I’m a more pleasant person in writing than in drawing. As for writing, I enjoy making a story’s first draft the most – the feeling that sometimes your idea moves so fast that your hand can’t keep up. I don’t like fine-tuning a story as much. It’s the opposite for my mother – polishing and fine-tuning are her greatest joys. Doubts arise when I’m formulating the text’s linguistic side, probably because I lack an education in linguistics, and those doubts aren’t the most pleasant part of my work. Although I envision characters firstly in image and only then in words, my moments of visual and linguistic creativity often coincide. For instance, when I get an idea for a scene and write down the initial version, I also illustrate next to the text right away – I “doodle” alongside my work; I sketch the character, but only start drawing the final pictures once the text is complete. I have different processes for writing a picture book and a story book. With a picture book, the number of pages is important – I draw my 32 or 40 pages as rows of little pictures on paper. There’s more spontaneity in writing a story book – for instance, some new character whose appearance I hadn’t intended at all can charge in and affect the course of the story in the middle of me writing it. Those are wonderful moments. At first, I have a general idea and know where the story should end up, but how exactly it ends up there becomes clear only over the course of writing. A character might grow and develop into something other than I had initially intended: for example, I might plan for a character to improve during the story – to develop in a positive direction – but while I’m writing, it turns out it just can’t be that way; a change like that can’t come from a real-life-, story-, or literary standpoint, and in that case, I go ahead and leave the character the way it was in the beginning. Because what’s a good, true character like? It’s a living character – its nature has to be lively, spatial; it can’t be a flat, two-dimensional cardboard creature. But I believe that condition also has to be met in the case of characters meant for adults. It’s possible to find a few more two-dimensional figures in children’s books. You can’t forget that the world of children’s books – just like the world of books for adults – has its own crime stories and “girly” works.

Talk a little about your work process. Do you devise a mental plan a long time before starting to write your books, think about the story and the characters, hatch the chick from the egg, and only then write it down; or do you rather seize upon a little inspirational fragment and start to expand it by writing and drawing?

This way and that. Some books come abruptly and all at once, driven by a strong momentary emotion. For example, Emili ja oi kui palju asju (Emily and Oh-So-Many Things) was written when I myself was on the brink of a change in life and was moving and threw away a huge amount of junk that had collected over the years. The picture book Kõik võiks olla roosa! (Everything Could Be Pink!) was done in a single evening, when my youngest son was a few months old and I was awfully exhausted and just beat, like mothers of few-month-old infants often are. I received an e-mail that evening from a friend, who comforted me and gave me strength and attached a lullaby for my tiny son. It moved me so much that I wanted to reply to my friend (who, at the time, was the father of a four-year-old girl) in suit. I can remember clearly how the entire story together with illustrations appeared in my mind over a couple of minutes while brushing my teeth in the bathroom that night. I planned to make it into a hand-drawn book with a sewn spine for the friend’s daughter, but I never got around to it. The book was, however, made instead into an app for a small British publisher, which was noticed in turn by the Japanese at a conference on e-books, and they wanted me to make it into a paper book. As of today, the little story has been published in Japan, Italy, as well as Estonia.

Emotional moments and clear memories that I encounter in life often find a place in my books. Sometimes when I see or experience something, I realize right away that it should definitely be recorded in a book. One time, on a dark and rainy autumn evening, I walked past a cellar-storey café where I could see a cake-making course going on. Young women, as beautiful as if they had stepped out of Renoir paintings, were gathered around a long table and decorating cakes. I stared at them in appreciation for a while, until one of them noticed me and smiled, at which I shyly turned and kept walking. That moment when I was standing in front of the window is written about in my latest book, Lugu Sandrist, Murist, tillukesest emmest ja nähtamatust Akslist (The Story of Sander, Muri, the Tiny Mommy, and the Invisible Aksel) – only that instead of me, a stray dog stands and watches the cake-making.

Where do you derive inspiration and ideas – more from your own childhood, or by observing children today, including your own? Could you highlight some topics that reoccur in your works, that come back time and again, that are continually on your mind, that seem the most important to you?

I get inspiration from both my own childhood and my own children, but mostly from life itself. I don’t think a children’s writer should necessarily have to have his or her own children, because a writer has personally been a child and might simply fit well with that world. It’s a little difficult for me to talk about topics that reoccur in my works. I’m not a very theoretical person and haven’t thought about my books in that way. But to me, it seems like my latest books often depict the friendship between a mother and her son – especially the relationship between a single mother and her son. The “ideal” family is widely depicted in Estonian literature, but in real life, there are actually very many children living with single parents. Children’s books frequently treat the topic as a problem, a sad topic, a situation that causes a child hardship, but at the same time we see in reality that a child can often be very happy in a single-parent family. Secondly, there tend to be a lot of characters in a large family, while in the case of just a mother and her child, you can delve deeper into the nature of the two characters. Critics have likewise said that in my books, the reader often encounters the topics of finding and staying yourself, as well as making the world a better place.

How important to you are style, words, and the power of the word when you write? Do you search a long time for the “right words”, for expressions that are as precise as possible; do you work using dictionaries, or are you rather a spontaneous writer?

I write relatively spontaneously and work on language more in the course of fine-tuning. I believe that a final text should be natural and not excessively polished, otherwise it acquires a kind of cramped feeling, a rigour, an artificiality that doesn’t come off as being natural or alive. For instance, you shouldn’t be too afraid of repetition when writing and search for a synonym to every word that tends to repeat. As for the choice of vocabulary, with some words, I sometimes stop and think that a child probably won’t know its meaning and that maybe I should replace it with a simpler alternative, but then I reckon on the other hand that it can stay just like that – let the child learn a new word or two when they read, too! Of course, you shouldn’t go overboard with complex words in a children’s book. As for editing, I don’t especially enjoy someone coming and “tampering” with my texts. I have a wonderful editor – Jane Lepasaar – who highly respects the author’s style and often says that if you’d like, you could write this part here a little differently, but you’ve got the opportunity to decide if you want to do so or not – the writer is foremost the one who creates the language. But if the text conflicts with the rules of Estonian, then she doesn’t disregard it. I find that some mistakes can be so characteristic of a writer that they’re a part of their style. Dialogue and colloquial language are important to me, but at the same time, I find that I can’t quite write in “kitchen language”.

What has interaction with your translators and foreign readers given you as a writer? Has it changed you or caused you to move in any directions that you wouldn’t have discovered without those contacts? What interesting or unexpected feedback have you received abroad? In what other languages would you gladly see your books published?

I’ve gained a great deal through interaction with foreign publishers and readers. I receive much more feedback from abroad than I do from home – more children’s literature reviews are written abroad than they are in Estonia. You can often even receive supportive feedback from the foreign scanner who scans your pictures into a computer, for example, and that’s brilliant. As a writer, I dearly need those kinds of hugs and pats on the back. When an Estonian editor half-grunts “I really liked it” to me, then that’s really saying something. You’re often pretty alone when you write and illustrate. I discuss draft versions with my mother in the case of longer texts, but with picture books, there aren’t that many people to consult. In France, though, I’ve felt like I’m not the only one interested in my work – the editor and publisher are really keen to see it and they’re very intrigued by what I do. And the French are very good at giving compliments, although I suppose publishers vary in France, too. The publisher I collaborate with, Rouergue, is able to encourage me to try new things, to develop – they help me to progress and transform in an artistic sense.

There’s similarly more reader feedback abroad – for instance, people look me up on Facebook and send me messages saying they really enjoyed this book or that one. I feel that the abundance or scarcity of feedback also depends on the publisher. I’ve been very lucky with my French publisher, and people notice and look forward to the books they publish in France – the books of mine they publish don’t fall into a “vacuum”, but rather receive readers’ attention quickly. French booksellers read a lot and are able to recommend works to readers. I actually believe it’s not necessarily important that this involves a French publisher in particular, but rather that I’ve had the fortune to work with people with whom I’m on the same wavelength, and who – right at our first meeting – were able to spot in my pictures what I personally regard as important. As an illustrator, I have a portfolio that I’ve shown to several publishers. It has pictures that I know are professional and please the experts, as well as pictures that I personally think are very good, but which might not speak to just anyone at first glance. Rouergue’s artistic director was the first publisher whose finger, when he was flipping through my portfolio, fell unmistakably upon those latter pictures, and he said “That one!” and “That one!”. That decided everything for me – I sensed immediately how very much I wanted to collaborate on something with them.

I have an education in graphic design, and I’ve always really liked the world of black-and-white pictures, where texture and lines play a more important role than colour tones. Rouergue encouraged me to make black-and-white picture books. In Estonia, the publisher and the purchaser prefer colour pictures in children’s books, even when it’s a story book (the fact that the story books I’ve published here [in Estonia] have black-and-white illustrations has been my own wish – the publisher has always been rather against it, saying that some people in Estonia don’t buy books with black-and-white pictures on principle). So, I can say with certainty that the book about a fish named Emili, and especially the story about Eli to be published this spring wouldn’t have come about without the French. At the same time, after doing two mainly black-and-white books – which I greatly enjoyed making – I felt like using colours in my next book. I spoke to the publisher about my new plans and proposed several options without emphasising my own preferences, and once again, the publisher picked out the same direction that had been my own deepest desire. So, I’ve simply been in luck with my own wishes and the publisher’s vision corresponding; with the publisher encouraging me to take the direction I personally want to go in. I’ve also received good feedback from Japan and Italy. I’d really like my books to be published in Portuguese and Finnish, too. Unfortunately, that hasn’t happened yet, and it seems like in Finland, they do prefer native literature to translations.

As for what I write, I see judgement-differences in terms of the texts. What people in Estonia notice most is my sense of humour and the inventiveness of the plot and my tempo. These things haven’t gone unnoticed in France, of course, but my texts have additionally been called poetic and philosophical there, for which I’m very grateful. I’ve consciously wedged more lyrical points in between the jokes and cheer in each of my books, and those are the places dearest to me as the author. I believe that a children’s book doesn’t have to be charged with positivity and liveliness from cover to cover – that other types of moods are necessary, too.

What do you think of the concept “children’s literature for adults”?

You can take the concept several ways. “Children’s literature for adults” can be seen as a writer doing his or her own thing under the guise of children’s literature, and writing over their audience’s heads. Another possibility is to discuss literature that’s meant to speak to children, but a very great part of which nevertheless doesn’t. The same phenomenon exists in the case of picture books, too. You could ask – should a picture book really only speak to a child at the point in time when he or she is a child; or should book illustrations also play a preparatory role? Can you draw pictures with the thought that the child will become a reader of higher literature, a museum-goer, etc.? Already at an early age, a child’s bookshelf could include books used to guide him or her towards art meant for adults. Because you do take the same child to the art museum and the art gallery; they’re not given a discount with art, just like how we don’t turn off a symphony playing on the radio when a child is around or insert a CD of children’s songs instead. So, why should we act that way with literature? For example, there was a great instance in France, where a teacher told me she read my book Härra Linnu lugu (Mr Bird’s Story) with her students and then took the class to the Dalí museum. For her, those two worlds were connected in some way. In my opinion, it’s not worth being afraid of the more serious and mature children’s book. You don’t have to keep a child solely in a childish “circus world”. The fact that a child also takes part in adult art, music, and literature – and in the adult world by way of it – is natural and developmental.

To finish, please describe your ideal creative day. Where are you, what’s around you, what are the weather and lighting and sounds, what kind of work is it, and in what quantity and rhythm?

I imagine my ideal creative day as the children for whom I write being somewhere else – at day care or at school. I’m home alone. There’s good lighting outside – the sun isn’t shining directly indoors, but it spills into the room and fills the entire space with light. Peace and quiet. I’m working on something captivating. I make a cup of coffee, and I feel good. I work most every day. I can sometimes get edgy if there’s a break between two books. I like doing work more than other activities, so self-discipline doesn’t take all that much effort. And even in the evening when I’m feeling tired, taking a shower or before going to bed, I come up with really good ideas on occasion.

Eva Koff (1973) is a writer and instructor. Koff’s play Meie isa (Our Father) won the 2001 Estonian Theatre Agency’s Play

Competition. She is also a screenwriter for the Estonian Television children’s

programme Lastetuba.Indrek Koff (1975) is a writer and translator. He has translated French literature and philosophy into Estonian, including works by Michel Houellebecq and Michel Foucault. Koff’s genre-bridging work Eestluse elujõust (The Vitality of Estonianness) won the Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Award for Poetry in 2010. Koff is also the author of several children’s books.