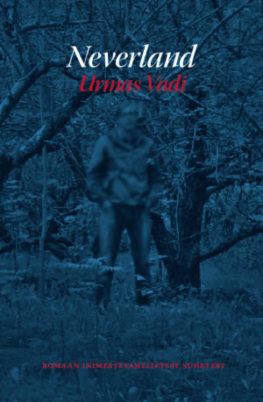

Urmas Vadi. Neverland

Kolm Tarka, 2017. 352 pp

Issues of identity remain topical in Estonian literature, and are addressed by Urmas Vadi in his newest novel Neverland. Although the original title is in English, Vadi delves deeply into Estonia’s social conditions, and the plot threads tightly throughout the city of Tartu. A large cast of characters marches before the reader and forms a nicely interworking ensemble, conveying a credible picture of present-day Tartu society. We find here people both young and old, who primarily belong to the middle class: something that has become increasingly harder to define.

The characters possess property, but it often appears like this property possesses its owners, giving them no joy. They have family ties, but even these tend to be a burden. Some have more, others less; some are one type, others another. And naturally, they have problems: the good old kind of problems without which there would be no literature. Some of these troubles and tribulations are of a medical nature, while others are more the legal type or concern morals, ethics, or identity. From this perspective, Neverland might not be so exclusively Estonian after all; rather, Vadi appears to trace the essence of humanism. He simply has the skill to immerse it in a familiar atmosphere, which is necessary for establishing believability, i.e. for literature to be literature.

Vadi himself remarked in a TV interview that as he was writing Neverland, he became intrigued by certain questions: Do we understand one another at all? Are we really able to help someone else when they have a problem or concern?

In the early 2000s, Vadi emerged as a talented screenwriter and producer who has always been a fan of good humor. There is also a good dose of comedy in Neverland, although it is frequently seen through tears. Can a rape accusation be funny? Can the delusions of an elderly actress who has slipped into obscurity be classified as humor? Can the possibly self-destructive desire of a young man – one whose father is an ethnically Russian, retired Soviet military officer – to be a real Estonian make readers laugh, despite the sensitive topic? Or will all these things simply make one break into tears?

I personally can’t say. Nevertheless, Vadi is highly capable of describing yearnings. Of describing all kinds of Estonians. All kinds of worlds. All kinds of lives. And the title itself alludes to this: a place, to which we’d all like to someday return, even if only in death. Still, the lives of Vadi’s protagonists (or are they more like antagonists?) don’t take exceptionally tragic turns. In this sense, the catastrophes that Vadi has his characters undergo are “cozy enough”, but can something really be cozy if it’s a perpetual everyday horror, something that makes you feel like life is disintegrating piece by piece, and that nothing is possible? Vadi at least describes this everyday brutality in a warm, melancholic way, and with a faint smirk at the corner of his lips. I suppose that’s just how life should be handled.

Peeter Helme (1978) is an Estonian writer and journalist, and anchors Estonian Public Broadcasting’s literary radio programs. Helme has published five novels. The latest, Deep in the West (Sügaval läänes, 2015), is a drama set in the industrial Ruhr Valley.