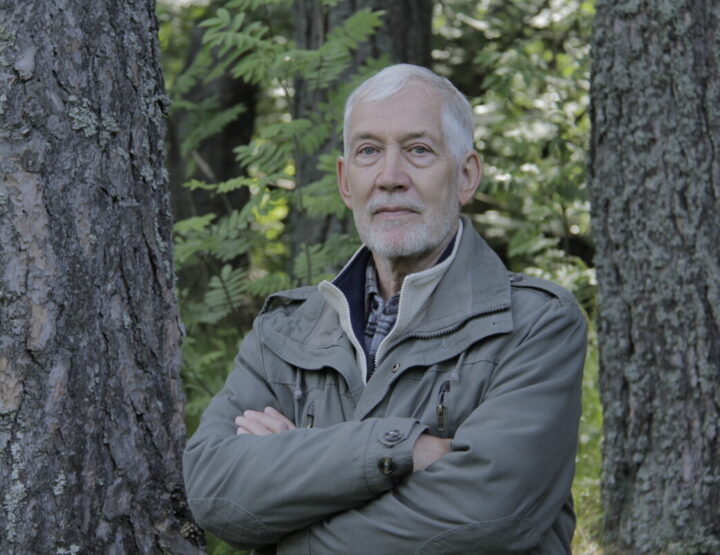

Andrus Kivirähk. Jutud (Stories)

Tallinn: EKSA, 2005. 279 pp

Since the publication of The Memoirs of Ivan Orav in 1995, Andrus Kivirähk has delivered to his readers plenty of texts in different genres, the only exception being poetry. He has written both for children and adults, both for the reader and for the stage. Starting with easy feuilletons in daily newspapers and proceeding to the novel The Old Barny (2000), a telling book that may crumble Estonians’ self-pride but which still has strong identity-creating powers, and which has already been translated into several languages, Kivirähk has successfully used all registers of the comic scale.

His latest book contains 13 stories, all presented with his characteristic verve and amassing of astonishing features. In the story “The Naked”, the growing effect of people who run around naked in a mediaeval town causes disorder and confusion. The two time levels in the story “The Holy Grail” adventurously mix together the epic romanticism of knights and the modern cult of consumerism. “Romeo and Juliet”, almost crossing the line between good and bad taste, tells us about a slightly backward Romeo with sodomite preferences and his attraction to a roe deer, Juliet, who is killed at a hunt to prevent them from sinning and whose meat is boiled in a cauldron. To be with his beloved, Romeo climbs into the boiling cauldron.

In general, it can be said that Kivirähk rapidly writes, rewrites and overwrites literature. This is, by no means, an overproduction, since by recalling good old dialectics we could say that quantity gives rise to a new quality and, using the new EU terminology, this attests to the sustainable development of Estonian literature. Kivirähk very often uses somewhat romantic or tragic arch-plots or basic patterns, and instantly starts to diminish their sublimity with his easy and ironic narration. The noble style with astonishing word order that is used in “Romeo and Juliet” is broken by vulgarisms that suddenly find their way into its vocabulary; chivalry that has been developed into half-idiocy or romantic love (“The Holy Grail”, “The Poor Student”) is repeatedly demeaned and used to pave the way for a Nordic barbarians’ looting raid into Europe. The latter takes place in the most outstanding story of this collection, “A Trip across Europe”, where three Estonian predators – a bear, a lynx and a wolf – take a trip to Paris with the aim of digging up Chopin’s shinbones, which are the best material for making drumsticks for the bear (also, an allusion to an old and popular Estonian children’s song) at a cemetery. On their way to Paris, the company eats a large number of German hares, Parisian cats and the poodle Louis, who is in love with the cats. Still, this is not only a looting raid but, by marking their progress with puddles on the bushes by the road, also an act of colonisation and a taking over of Europe.

An Estonian drum and Polish drumsticks, ennobled by the soil of a Parisian cemetery, remind us of the Polish master of the grotesque Sławomir Mrožek’s short story “The Case of a Drummer”, where a drummer who day and night plays his drum in honour of his general is arrested as a traitor. Kivirähk’s humour and fantasy may balance precariously, sometimes hurting the feelings of an ordinary decent citizen. At the same time, they point out the chances of solving the tensions caused by exaggerated political correctness, with literary means and methods. Kivirähk’s loudly drumming grotesque plays an important role in modern Estonian literature.

Asko Künnap. Kõige ilusam sõda. (The Most Beautiful War)

[Tallinn] Näo Kirik, 2004. 95 pp

Non-existing worlds can easily be found in literature. In good literature, we can always feel this brave striving for a better world, even if it is conveyed by representing the existing depressing world.

Asko Künnap’s (1971) collection of poetry The Most Beautiful War is just such an attempt to create a bright new world. The more so since the poetry world of this book is full of topographical references, mixing existing places that can be found on a map or in some cityscape with fictive and witty others. The packing of things for a trip in the opening poem of the book, “This Greatest Witchcraft of All”, inspires its readers to start a journey of their own. Southern Estonia, New York, Amsterdam and many other places in the world, mentioned and described in the text of the book are contrasted with photographic illustrations depicting some words that specify, usually, a fictive location, which have been written on the palm of a hand, resembling a spider’s web or on the palm of a hand that has been stitched with a needle and thread. These illustrations, which hint at a parlour game, are enjoyable poems in their own right, emphasising the uniqueness of the book as a whole. This is one man’s conceptual work of art, where Künnap’s text, photos, design, layout, the font of the text, and sometimes even its size and angle on the page create an entirely different and novel effect. The Most Beautiful War principally differs from familiar – classical in appearance – collections of texts, which can, either partly or as a whole, be re-presented in collected and selected works and in anthologies. It justifiably belongs among the 25 most beautiful Estonian books of 2004, just as Künnap’s previous collection of poetry, And the Lizards Replied, which was also given the Estonian Cultural Endowment poetry award in 2003, was voted among the most beautiful Estonian books of the same year.

One of the most suggestive poems in the book, “Into the Ebony Darkness!”, features a character called Dreamwitch. Dreams and witchcraft seem to be the words that carry the key meanings in Künnap’s poetry, leading us, gently and without any special attempt to shock, towards a surrealistic approach to the world. A particular kind of strangeness is revealed in the clinging together of the real and unreal world, wakefulness and the dreamlike, the routine and fairytale-like.

But why such a title – The Most Beautiful War? The answer obviously follows from what was said above – this war is waged against the routine and habitual order of the world, using an enjoyable poetic language of images, reviving already forgotten meanings of words and creating unexpected associations. A beautiful war is the primeval polemos in the modern world. The last photo of the book – the author pedalling on a stationary bike against the background of speeding cyclists – symbolises an abandoning of the rashness of the world. This is the war that is waged with words in the name of beauty.

Jaan Kaplinski. Kaks päikest. Teistmoodi muinaslood. (Two Suns. Another Kind of Fairy-Tale)

Tallinn: Tänapäev, 2005. 264 pp

Jaan Kaplinski has been fascinated by ethnology, folklore, and exotic places and peoples since the beginning of his literary career. He attracted attention as a poet in the 1960s mainly with his incantation-like poems; he has written essays and travel books and lately also conceptual prose. His new book, the collection of fairy-tales Two Suns, issued in the new book series “My First Book” of the publishing house Tänapäev, is a return to a simple life close to nature, unspoilt by modern civilization.

The fifty stories told by Kaplinski may seem quite extraordinary to a reader used to modern literary fairy-tales of European tradition. They are too full of the freshness characteristic of traditional cultures, too full of the joy of discovery, situations that may seem absurd to everyday logic and childish attempts at explaining the order of the world, and there are too many stories that resemble myths of origin. Kaplinski has drawn from the treasuries of stories of many peoples, but he presents his texts without any ambition for artistic elaboration, in a neutral and unadorned language. The childhood of humanity is talking to us in these tales, the more so since he has selected stories from Australian aborigines, natives of South and North America and the islands of the Pacific Ocean, African tribes and Nordic peoples. Europe is represented only by Estonians and Irishmen.

Kaplinski has repeatedly criticised the consumer mentality of the modern world in his articles; he has sensitively discussed ecological and global problems. He actually talks about the same things in his fairy-tales, a sustainable way of living. Therefore, Two Suns is not only a children’s book, but also offers spiritual refreshment to all thinking people. His skilful and unobtrusive narrative style is a clever pedagogical trick; the moral of his seemingly exotic stories spontaneously reaches his readers. These stories contain a unified syncretistic world view, and the rest of his work offers numerous examples of his attempts at recreating it again and again. He has repeatedly claimed that he is no writer and that his work is no literature, no poetry, but simply a declaration of love for the world, and he has foretold the loss of aesthetics. This is a bright and beautiful book, greatly enhanced by Kalli Kalde’s congenial illustrations, which are based on motifs from the folk art of many different peoples.

Betti Alver. Koguja: Suur luuleraamat. (The Collector: A Great Book of Poetry)

Tartu: Ilmamaa, 2005. 599 pp

Of all the noble and representative women of Estonian literature, the works and personality of Betti Alver (1906-1989) are among the most remarkable. Alver made her prose debut in 1927, but she soon became known as a poet. Her first collection, Tolm ja Tuli (Dust and Fire), was published in 1936 and her fame was launched with the publication of the anthology Arbujad in 1938, which brought to literature a group of new authors, all of whom later became literary classics, including Heiti Talvik, Uku Masing and Bernard Kangro. The fate of these erudite and original poets, who appreciated both ethical maximalism and perfection of form, was cruel after WWII. Talvik, who had married Alver, was arrested and died in Siberia, having had published only two collections of poetry. Masing, being a theologian, had to spend decades in internal exile. Kangro fled Estonia and lived in Sweden, becoming a publisher and prolific author. Alver was accused of formalism and was banned from publishing – her next collection of poetry was published only in 1966.

With the exception of a few lyroepic poems, Alver published only five collections of original poetry, the latest of which came out in 1986, but all her collections became landmarks in Estonian literature. Characteristically, she edited and greatly changed her texts when preparing selected collections and new editions of her works. Her work with words in refining poetic texts to achieve even greater exactness and richness of vocabulary is awe-inspiring.

The Collector, compiled by the Docent of Estonian Literature at the University of Tartu Ele Süvalep, is the most exhaustive collection of Alver’s poetry, having the justifiable subtitle A Great Book of Poetry. But thinking about the striving for perfection of the poet, this book is a compromise between a textual critical volume addressing scholars of literature and a book of poems meant for regular lovers of poetry. Instead of containing different original and revised versions of the texts, the book is based on first editions, with the years of first publication added.

The Collector offers the best possible integral overview of Alver’s poetry. Her strict culture of poetic form, passionate need for experiencing the new, defiance of routine, the petty bourgeois and common beliefs, her proud proclamation of spiritual freedom in spite of cruel times, and the problems of the relationship between life and art were later complemented by mythical and somewhat autobiographical subjects, always crystallising into pure lyric that ennobles the human spirit. For the following generations, Alver has always been an embodiment of the ideal poet, uniting deeply personal feelings with the fate of her people and of humankind. Even her playfully created self-myth carries an unwavering ethical load.

Jüri Talvet. Unest, lumest. (About Dreams and the Snow)

Tartu: Ilmamaa, 2005. 77 pp

Jüri Talvet (1945), Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Tartu, continues his already characteristic style in an even more concentrated way in his sixth collection of poetry, About Dreams and the Snow. On the one hand, this is the poetry of a much-travelled scholar and cosmopolitan; on the other hand, this is the deeply national credo of a poet who has his roots in his home and family. The mother-tongue whisper of falling leaves alternates with a row of exotic pictures and images; invisible relations tie together Talvet’s home town, Tartu, the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea, the deserts of Morocco, and the bees of Córdoba and home. These laborious insects, which have become a fixed image in Estonian poetry, enter into a classical relationship of the familiar and alien. This binarity, however, never exhibits any sharp hostility or opposition; rather it mixes and searches for a common ground which can enrich different cultures, and is in accord with Talvet’s theoretical discussions on symbiosis. Whenever Talvet displays a critical or ironic attitude in his poems or exhibits social sensitivity, he delivers in carefully measured doses, whether he is criticising terrorism, planes that drop bombs from the sky of Baghdad, or fashionable theoreticians of postmodernism.

Instead of giving direct judgements, Talvet’s poetry speaks to us polyphonically, and we can clearly recognise the voice of a child, just as in his earlier books. The child’s voice has a purifying effect similar to the act of tossing lecture notes on Lenin’s works into a rubbish bin in the poem “The World Begins Again”. Purification means returning and starting anew, enriched by previous experience. Having its roots in European humanism, Talvet’s work is at the same time a poetry of going out into the world and returning home. As in T. S. Eliot’s definition of a classic author, maturity of feelings, thoughts, and expression are the most appreciated features of Talvet’s poetry.

Sass Henno: Mina olin siin. 1 : esimene arrest (I Was Here. 1. The First Arrest)

Tallinn: Eesti Päevaleht, 2005. 200 pp

Sass Henno (1982), the winner of the 2004 novel competition, is the youngest ever winner of such competitions in Estonia.

His debut novel, I Was Here, is about a youth gang at odds with the law and opens with a scene in which the handcuffed protagonist is writing his statement at a police station. Briefly, the book is about juvenile delinquency, and the title statement forms its frame. Henno has modelled his novel on Anglo-American shock literature (Chuck Palahniuk, Bret Easton Ellis and others).

The main character Rass and his gang are young men who come from poor circumstances and do not have many options. They have grown up in a budding capitalist state, where money is the ultimate value and less well-off boys are ready to do almost anything to get money, since the whole life of their neighbourhood revolves around things that can be bought. Money could, of course, be obtained by hard work, but it would be too toilsome and the sweet life they are striving for would be too far away. Therefore, they prefer petty theft, drug traffic and other such activities. By chance, this gang of minor petty crooks meets the real underworld. The meeting is harsh and scares the boys. In spite of their seemingly daring and arrogant fast living and existence outside the law, they expect still more of their lives. They also have the need to belong somewhere and be understood. The protagonist expects still more – sincerity, honesty and safety – shown by his protective attitude towards the sister of the gang boss, who has been sexually abused by the others. But where do the suburban youths belong, anyway?

Sass Henno reveals the years of childhood and youth of a new generation, together with all their problems. Naturally, there is nothing new in these problems. Critics have compared Sass Henno with Kaur Kender, who debuted about a decade ago with the powerful novel Independence Day, also about crime. Henno has discovered that cruelty, similar to that in Kender’s novel, is in his case accompanied by unexpected and veiled tenderness and even chaste views on life, hidden under external bravado. Henno’s characters speak a vivid and strong language, often a street language, often a verbally offensive and obscene language. The author easily creates new words and, having worked hard, is remarkably skilful and exact in his vocabulary. In a newspaper interview he stated that he writes about the life of his generation in the suburbs, outside the centre of the city. He speaks about marginal areas, and about those who were not born into the protected circle of property owners, but who have to fight for their place in the sun, at the same time having no clear idea about that place. Their world is split in two – their own and that of the aliens, who are treated according to a different morality. But the youngsters lose everything.

Henno has planned I Was Here as the first part of a trilogy. He will travel on with his characters. The question is where are they heading?

Jaan Kruusvall. Sinetavad kaugused: valitud proosat (Blue Horizons: Selected Prose)

Tallinn: Eesti Raamat, 2004. 420 pp

Jaan Kruusvall (1940) debuted in the 1960s and published his first collection of short prose in 1973. Kruusvall is best-known for his play Colours of the Clouds, staged in 1983, which honestly spoke of Estonian people in the time of war (WWII), especially about their dilemma of whether to escape abroad or stay at home on the arrival of the Soviet army. Several of his following plays, contrasting people with a society which is endlessly indifferent or hostile towards humans, also received acclaim. Besides drama, Kruusvall’s other favourite genre is short prose. He has more than once written the best short stories of the year and won the prestigious Friedebert Tuglas Short Story Award.

Blue Horizons contains the best of Kruusvall’s short stories, and two short novels, The Autumn Divertissement and Nocturne by a Lake, the latter about a man and a woman, their brief encounter and their dull dreams, which do not make them act but fade and seep away like a stream in a desert, although they both think about each other all their lives.

Kruusvall’s world does not contain heroes, but rather small people, who live their eventless dull lives. “How dull and monotonous is our life actually”, admits one of the characters in The Autumn Divertissement. People’s lives are empty and incomplete; sometimes they seem to wake for a moment from their slumber and feel that life is passing them by. Often, Kruusvall’s works start vaguely with the words “suddenly” or “one morning”, as if wishing to emphasise that life is so monotonous that it does not even make any difference which part of it is under observation. The world is irrational, existence is absurd and there is no escape, causing melancholy and even tragedy. Fortunately, people usually do not sense this tragedy. This is an eventless world; everything that happens is diminished and becomes unimportant or, on the contrary, everything has its meaning, but all meanings are equal and even great things are reduced to smallness, and the unimportant and routine acquire a central place and are repeated in endless new versions.

The novella “Life” starts with the statement, “I exist”, and continues soberly, “but I don’t jump for joy and announce the fact that I exist to the world. And I don’t see other people boasting about the fact that they exist. Rather, it is a regrettable fact.” The first person narrator still believes that his dreams will come true some day, since “It cannot be that everything will forever remain as it is now”. And when the narrator hopes that “life must get better”, the reader can sense the author regretting that somebody should still hope this way, since Kruusvall’s world image is totally sceptical; the atmosphere he has created approaches the absurd, but it is often enjoyably exact and almost palpable.

Indrek Hirv. Klaaskübara all (Under a Glass Hat)

Tartu: Ilmamaa, 2004. 168 pp

Indrek Hirv (1956) is a poet, translator and artist. He studied ceramics at the Estonian Art Academy and later also worked as an art teacher. But foremost, Hirv is a poet par excellence, a troubadour who established himself on the Estonian literary scene with his first collection of poetry in 1987. He has published 14 collections, all of which are centred on the erotic experience of love. Hirv often writes classical, stanzaic, playful poetry full of images; his work is neo-romantic, dramatic, and sometimes even mannerist. Several of his collections contain, besides his own work, translations of his favourite poets, most important among them being the French Symbolists of the early 20th century.

The new book, Under a Glass Hat, brings together the poet and the artist, presenting a selection of Hirv’s essays on various aspects of art. Here, Hirv talks about life and art, people, the world and metropolises, but with the greatest emphasis on the town of his youth – Tartu – portraying with a sensitive quill its people and atmosphere.

Hirv comes from a family of artists. He has abundant memories of that generation of artists who had received their education at the legendary pre-war Tartu art school “Pallas”. His warm, exact and laconic portrait sketches of older Tartu artists make his book especially attractive. People very often talk about the so-called ‘spirit of Tartu’, describing the uniqueness of Tartu, its way of life, and its nostalgic elusiveness, which often may fade into a provincial idyll. Hirv is rather, in his reminiscences, a gentleman and a citizen of the world. He has very clear views on the pre-war generation of Tartu artists, and he is impressed by their loyalty to their principles. Hirv has mastered the supple art of describing – he sees details and also sees how they reflect a unity. He also portrays some Estonian artists whom he knows only through their works and books written about them (J. Köler and others), trying to highlight the most characteristic aspects.

Besides Tartu, he writes about Paris and New York. Many famous men and women are known for their autobiographical notes on well-known places of the world. Hirv’s impressions of these places are autobiographical too. But he also portrays the past and attempts to revive a place that most of us have no access to – the legendary pre-war Tartu and the role of the “Pallas” art school in Estonian art history.

Õudne Eesti. Valimik eesti õudusjutte. (Horrible Estonia. A Selection of Estonian Horror Stories)

Tallinn: Varrak, 2005. 511 pp

This voluminous collection contains 31 horror stories selected by Indrek Hargla (1970), the best-known and most productive Estonian sci-fi author, who has published eight books in the genre. He is also the author of the longest and the most thrilling story of this collection, titled “Väendru”.

Horrible Estonia is one man’s view of the development of the genre in Estonia during the past 140 years. Several other equal, but certainly different, selections could be placed beside this book. In his preface, Hargla states that, by presenting this book, he wants both to promote and develop the genre in Estonia. To map the tradition of Estonian horror fiction, Hargla has included different stories written mostly on Estonian themes by authors of different periods. Some of these stories contain only a few elements of horror and thrill, while some of them are true horror stories.

One of the selection criteria was the presence of supernatural elements in the stories. The compiler seems to have preferred horror stories on ethnical themes, avoiding texts inclining towards the absurd and grotesque as being too postmodernist. Therefore, many a modern author who writes short stories with elements of horror was excluded from the book.

The range of Estonian horror fiction selected by Hargla is still quite wide. Horror and fantasy prevail, but we can also find quite realistic crime stories or adventures; sci-fi occupies a marginal place. To stress the length of the tradition, the collection opens with a story by Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald (1803-1882), one of the founders of the Estonian literary tradition. A story by August Kitzberg (1855-1927) is about a werewolf (the author later developed the same story into a famous tragedy). Canonical texts have been chosen from the works of the Estonian literary classics A. H. Tammsaare, Fr. Tuglas, A. Gailit, J. Jaik and P. Vallak. All of these authors have, during their long careers, written a number of stories in this genre.

Besides the classics, the collection contains texts by most of the younger authors who have published outstanding stories, mainly sci-fi, in recent decades. In addition to them, there are also some marginal authors, whose sole contribution to Estonian literature has been a few horror stories, and some texts were written to order specially for this book. Quite realistic adventure stories stand here side by side with all kinds of the undead, werewolves, ghosts and spectres, elves, witches, and even the Devil himself.

How can Estonian horror fiction be characterised? Many authors lean more or less heavily on folklore; this is a characteristic feature of Herta Laipaik’s work. Horror, fantasy and sci-fi literature, which have gained a great deal of popularity in Estonia during recent decades, combine international motifs with local ones. For example, Hargla’s “Väendru” starts as a realistic historical story, but ends in a horrible scene of the execution of a witch, preceded by the redeeming death of a visitor from the realm of elves.

The selection offered by Horrible Estonia is amazingly wide. But if we search for the most typically Estonian and alternative horror, we can find it in the work of an author who was not included in this collection – Andrus Kivirähk. Numerous folklorist characters are in action in his extremely popular novel The Old Barney, moving around before and after All Souls’ Day, all horrible enough, but at the same time funny, shiftless and awkward. Estonian horror fiction is definitely alive and branching off in different directions.

Olavi Ruitlane. Kroonu (In the Army)

Räpina: Väiku Välläandja, 2005. 164 pp

Olavi Ruitlane (1969), the winner of the second prize at the 2004 novel competition with his novel In the Army, was born and went to school in the town of Võru. Now the author earns his living as a designer of web pages, but he has held a number of very different jobs in his life (a boiler operator, tractor driver, herdsman, radio broadcast editor etc). He has already published two collections of poetry and a youth novel and participated in the publications of the Tartu Young Authors’ Association. Being an enthusiast of the ‘Võru language’, which is based on Southern Estonian dialects, he writes in both the Estonian and Võru languages.

The novel In the Army became popular right after its publication; the reading public enjoyed its pleasant humour and the subject matter – stories about the Soviet Army – which has been widely talked about but has very rarely been written about in literary texts or recorded in memoirs. The Estonian title of the book, the word kroonu (originating centuries ago, meaning matters related to the state), reaches into the archaic layers of military folklore and actualises the experience of all the Estonian men who have been conscripted into the Soviet Army. Military service lasted for two years then and even for three years in the navy. Ruitlane characterises the life of a conscript as follows: “The only ways of relating that the army sergeants knew were abuse and foul language and the torturing of recruits, for which they found enough opportunities in the regulations of the invincible Soviet Army and from their own inventiveness”. Ruitlane himself served in the Soviet Army in the city of Arkhangelsk in 1988-1990; he uses his own autobiographical experience and makes informed generalisations.

In the Army is a sometimes quite crazy story about three Estonian young men and their adventures and misadventures in the army. The craziest parts of the novel are related to quite an irresponsible prankster, Peeter Keerits. Among his mates, Stepan Siska is a positively-minded and stoic boy from South Estonia, and Heino Ülane is a mamma’s boy, who ‘becomes a man in the army’ even in the literary sense, since somehow he manages to have numerous adventures with women as well. The pranks that Keerits organises are mostly good-natured and funny, but still balance between good and evil. Keerits often impersonates a collective hero, doing things that come straight from soldiers’ folklore, such as his feeding officers the drugs that had actually been meant for soldiers to diminish their sexual urges. Keerits does not think about the results of his jokes and about the effect they might have not only on the system, but also on the fate of his mates, since he may risk damaging army equipment and sometimes even threatening the lives of his friends. He is happy when having fun, which helps them all bear the absurdities they have to take part in. Some material benefits are even more welcome, since in the army only those who are caught get punished, not those who steal from the system; as a rule, the three pranksters always defeat it.

In the Army, naturally, exposes the absurdity of the Soviet order and structures, their misanthropy and stupidity. We can talk about the novel as the ‘Estonian Good Soldier Svejk’, containing equal parts of healthy humour and rough realism. The three Estonian young men respond to the system in the same rough way as the system treats them. This short novel written by Ruitlane still lacks the broad range and scope of Hasek’s immortal book, but it has already earned itself a place among the classics of Estonian military humour.

Kristiina Ehin. Kaitseala (The Protected Zone)

Tallinn: Huma, 2005. 160 pp

Kristiina Ehin (1977), who was born into a family of writers, has made every attempt to escape the fate of a writer. However, she has become one of the most successful poets of the younger generation. Her fourth and most voluminous collection of poems, The Protected Zone, is a true bestseller. Her previous collection of poetry, The City of Swan Bones (2003), sold out three printings.

Ehin does nothing to appeal to her readers. On the contrary, she claims that she writes about the things that only she herself feels attracted to and touched by and declares that she does not strive for popularity.

Ehin wrote The Protected Zone while living on the small island of Mohni, a nature reserve off the northern Estonian coast. She spent a year on that island, working as a guard. For her, living on an island meant both an ideal and a real life; there she could best experience reality. This life, such a departure from the routine, became kind of a frame for her: it was a protected zone, where it was easier to find herself and to be creative. In the book, poems alternate with fragments of the diary she wrote on the island, so that the book is also kind of a document, containing poems that ‘really happened’ and a real diary, reflecting the everyday events and thoughts of the author. The Protected Zone is the author’s spontaneous talk with herself – “Living on an island, I want again to learn to delight in people”, she says, and describes the process.

The collection reflects a worldview that appreciates nature and speaks against urbanism, expresses the wish to do something real and unique, and to write literature that is more natural than literature usually is. We could even say that Ehin wants to write as naturally as a folk singer sings; she wants to tell us about the singer’s world – about the role and the feelings of a woman, about nature, the seasons and the circle of life. She wants to write about small but eternal things. Her aim is to find rather than to make an effort and search for a specific Finno-Ugric worldview, or one characteristic of the Orient. Her wish is to express protest against the fact that for many people life is simply a senseless drifting along with the modern times and with the needs and values imposed on them, which are not related to their own real selves, which they have not yet found. Her poetry is a poetry of images, and her protest is mild rather than categorical. She attracts her readers with wholeness and élan; the beauty of her verses fascinates her readers as if showing them something that seems to be unreachable and tempting, although, at least theoretically, everyone who really wanted to do it could live a reclusive life in some remote corner of Estonia.

© ELM no 21, autumn 2005