Aarne Ruben. Volta Whistles Mournfully (Volta annab kaeblikku vilet)

Tallinn, Tänapäev, 2001. 352 pp

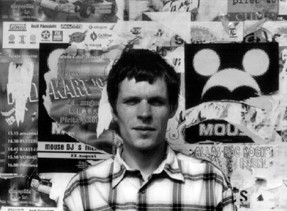

Aarne Ruben (29), a student of philology, who has worked as a journalist, was the winner of the latest novel writing competition. His winning novel earned only praise from the jury of the competition and its reviews have mostly been good. The author himself said that his aim has been to write an avant-gardist novel that would reflect life through humour and absurd, to make it a funny book without anything gloomy or sad in it.

We first meet the main character Gustav Kalender in Tallinn during the revolution of 1905, when he is a worker at the factory called Volta. He participates in revolutionary events, but to fighting for freedom, he prefers a beautiful girl, whom he follows when fleeing his hometown. He accidentally kills his rival in a fight and is sent to Siberia. We next see him some time later, in the company if Dadaists in Zurich during the WWI. This chapter of his life differs much from the period of the first Russian revolution in Tallinn. Now he is in the midst of an intellectual carnival – a province boy in the centre of modern art; he associates with Tristan Tzara and Vladimir Uljanov and has a wonderful career as a dadaist artist – the ideas of revolution and the ideas of dada are absurdly very similar to each other. After thirty years we meet him again. Gustav is back in Estonia, his pockets are full of money; he is very much interested in books that have been published when he was away, but also in old girl friends. Already the beginning of the book give us an overview of the later years of Gustav’s life. He has a nice life on the income of a glass blower and he relates his adventures to a young man, who reminds him of himself in the best days of his youth.

Ruben’s novel is full of intertextual references, the key words of the work are parody, pastiche and anecdote. Even his characters rather are literary abstractions than real people. As such, the novel would be an enjoyable piece of reading especially for intellectual audience, familiar with historical characters and events that crowd the book. The novel requires a reader who enjoys playing games, who understands the clichés that are parodied, who can distinguish between truth and fantasy and who would not take the author’s somersaulting thoughts as historical truth. The main character is presented as a kind of national archetype; at the beginning he is brave and venturesome, but quite simple-minded, like a real mythical hero. Tumults of life refine him and a good soldier of a leftist party becomes a pleasant rouge and a man of the world. Volta Whistles Mournfully is a stylish intellectual game containing the signs of the Estonian culture, and those of the world culture and history, of the beginning of the 20th century.

Arvo Valton. A Foundling (Leidik)

Tallinn, SE & JS, 2000. 236 pp

Arvo Valton (1935) belongs, just like Enn Vetemaa, to the powerful generation that entered the literary scene in the 1960s. For some decades he has even been considered the best Estonian short story writer. His typifying skills led him to creating model situations; his prose was characterised by hyperboles, the grotesque and satire. Later, he was interested in history, analysing the collective unconscious and was keen on myth creation. In 1989 he published a bulky novel ‘Depression And Hope’ (Masendus ja lootus) about the life of people who had been deported to Siberia – one of the first works of fiction written on this subject. Many of his short stories have been translated into other languages.

A Foundling is Valton’s 46th novel. The plot unravels in the years 1987-88, before the beginning of the Singing Revolution. The book depicts the so-called war of phosphorite, when the whole nation fought against the opening of new phosphorite mines in North Estonia, which threatened to cause both an ecological catastrophe and a social disaster, as the Soviet authorities planned to bring in thousands of new workers from Russia to work in these mines. Vetemaa presents the events that happened ten years ago through the eyes of a writer, a scientist, a punk, a dissident, an artist and others. His characters participate in meetings, gatherings and demonstrations, as well as in secret discussions in quiet offices. We can guess at the prototypes of central characters, well-known public figures can be found as episodic characters. As a ‘must’ in a ‘real’ novel, the work also contains sex and crime scenes besides the political ones. Olter, a writer, finds a young homeless Russian boy, whom he and his wife adopt, because they themselves could not have children. The theme of a Russian foundling allows Valton to focus the action of the novel on the fate of one person, but it also lets him discuss social and national problems. The unfortunate foundling is finally killed by his former friends from the streets, who are jealous of his new good life. Something symbolical could be seen in the fate of the foundling. Some episodes in this otherwise realistic narrative seem to hint at the possibility of adding a symbolic, mythical plane to the novel, but the rather weak generalisations do not allow them to rise to the foreground, and such hints merge into the trivial system of the work. Valton is a fluent narrator and a passionate politician, but as a realistic chronicler of history, he does not appear especially fascinating. This work has an interesting subject, the author relates current affairs with a certain playfulness, but he has failed to produce convincing generalisations.

Mats Traat. A White Bird (Valge lind)

Tallinn, Virgela, 2000. 320 pp

Mats Traat. Biographies from Harala (Harala elulood).

Tallinn, Kupar, 2001. 195 pp

Mats Traat (1936) debuted in the 1960s together with the powerful new generation (Jaan Kaplinski, Paul-Eerik Rummo, Arvo Valton, Mati Unt, Enn Vetemaa and others); he is one of the pillars of Estonian prose of the second half of the 20th century. A White Bird is the ninth volume of his monumental series depicting country life. The first volume of this series, Let’s Go Up to the Mountains (Mingem üles mägedele), was published in 1987; it began with the wedding of a young farmer Hendrik in 1885. The action of A White Bird takes place in the 1920s, in the first decade of the Estonian Republic. Hendrik’s aim in life is building his farm. Establishing a strong foundation to one’s life is not easy, each time when it seems that things have become easier, another obstacle looms ahead. This time it takes the form of fatal news that Lilli, Hendrik’s young second wife, has fallen ill with tuberculosis, which kills her in the end of the novel.

Traat is one of most obstinate narrators in Estonian literature; he pays no attention to postmodernist games and continues his realistic epic series, depicting country life in the literary style of the first half of the 20th century, telling about the fate of the nation over a long period of time. A White Bird can be read as an independent work, just as many other parts of this series, but in the general context of the great epic its voice is much more impressive.

Biographies from Harala is a representative work of Traat as a poet – a collection of powerful epitaphs, where the dead, buried at the imaginary Harala cemetery, tell us about their lives one by one. (Here Traat continues the tradition of E. Lee Masters. He even refers to his work by letting one of the characters, who had gone visiting his sister over the ocean, die and be buried at Spoon River graveyard.) As a whole, these biographies give a monumental mosaic portrait of Estonian village life. The first biographies were written already forty years ago, the first selection containing 55 biographies was published under the same title in 1976. The present collection of Harala biographies contains 168 ‘biographies’. Each compressed story, most of which have clearly been inspired by real life, could be expanded into a short story or even a novel. The characters tell their stories laconically, very seldom one of them mentions some others, and there are no author’s comments. The people resting in their graves are mostly simple country people; some of them had gone to seek their fortune in towns. But all of them had to admit that they had not found what they had been searching for; things they had been expecting had not happened; they had been shaped by their lives; nobody had ever wondered what they had been thinking.

The last part of the book was written during the recent decade. Life in the new Estonian Republic has shortened many a path to the Harala graveyard. Traat is very sensitive to social factors and true to the viewpoint of small people. The general atmosphere of these biographies is joyless, Estonian life depicted as dramatic or even downright absurd.

In 1977 the first edition of Harala biographies was awarded the annual literary prize. It is remarkable that even then the author did not falsify the recent history of Estonia. During his literary career of forty years, Traat has been true to his once chosen viewpoint of hard-working uncompromising people, who have often been conquered by life, and he has not been affected by censorship or fashionable trends.

Kärt Hellerma. Kassandra

Tallinn, Hotger, 2000. 214 pp

Kassandra is the second novel of the journalist and literary critic Kärt Hellerma (1956) – a work written by a modern, intelligent woman author. The main character Kassandra works as a style editor at a newspaper. She would be able to succeed in life, but she is not success-oriented and hates market economy. She is a sensitive woman with a shaky self-confidence. The greater part of the book follows her feelings and states of mind. A very important person for Kassandra is Moses, a gifted and admired musician, a prince who has awakened her hidden talents. Moses is not only satisfied with spiritual love, he seeks also carnal love, which disgusts Kassandra and makes her suffer. Social criticism is as important in Kassandra’s monologues as her spiritual search for her inner self or transfiguration; such aspirations require the denial of vulgar and selfish reality. Kassandra is writing a book, this activity is also related to her striving for liberation through the spiritual. Everyday life has only been sketched, Hellerma’s novel mainly moves on a metaplane. Kassandra raises two sons and goes through the pains and worries of a woman author; there are allusions to Virginia Woolf and the endless problems of a woman author, how to join together freedom, required for successful creative work, and tasks assigned by society.

Kassandra expects to find a solution by leaving the country together with her sons. Escaping the reality of life is the main theme of the whole book. The novel is stylish, it is rather static and contains many familiar problems and deliberations. Estonian critics have found references to feminism in Hellerma’s previous novel Alchemy (Alkeemia) and to a lesser extent, also in Kassandra. We can naturally talk about a woman’s viewpoint when discussing a woman author’s work, the characters of which are also women, but some reference to women’s problems still does not give us grounds to call Kassandra a feminist novel.

Mart Kivastik. Plays (Näidendid)

Tallinn, Eesti Keele Sihtasutus, 2000. 282 pp

Mart Kivastik (1963), belongs to the younger generation of Estonian authors. He has found recognition with two collections of short stories and a short novel, but he has also written film scripts, travel stories and humorously twisted portraits of bohemian figures of culture. His plays, which have been translated and staged in Lithuania as well as in Estonia, have caused a pleasant stir among the audiences in the recent years. Plays, containing five drama texts, earned the author the Estonian Cultural Endowment’s annual drama award.

At first sight, Kivastik’s plays seem to be only about rough humour and no deeper sense, but after getting deeper into them we realise that behind the often loutish behaviour and vulgar language of the characters we can see the author’s defiant tenderness and humanitarian pathos. These texts are the best and most original proof to the actually trivial statement that we come from our childhood and we carry it always with us. The two thirty-year-old characters, two losers form the play ”Peeter and Eerik” meet in a room that reminds us of a Soviet pioneer camp; they talk about J. Verne’s books, eat candy, make some half-hearted efforts on sports, think about their childhood and make something that ”very much resembles a chair” – doing all this as ”not to waste time”. In the end, the old hand Peeter and the newcomer Eerik form a moving male friendship, which is enhanced by romantic music and starry sky.

Kivastik’s other plays are characterised by nostalgic atmosphere too; scanty and slightly old-fashioned attributes seem to fulfil, besides being the signs of the depicted period, also the aim of smart pastiche making. The same stands for ”Happy Birthday, Leena!” (”Õnne, Leena!”), which was given an award, when it was still in the form of a short story. Now it has been rewritten as a play and it has been successfully staged in several theatres. Here a slightly sentimental and kitschy atmosphere takes the reader’s imagination a hundred years back in time. The author follows the spiteful relations of two eighty years old spinsters, getting now and then back into the Baltic-German manor where they had spent their childhood. Differently from the young lady of the manor, who had killed herself, the sisters have not experienced love, and their complexes are followed with a sympathetic smile.

Kivastik often puts his characters into absurd situations, such as in the play ”Our Father Which Art” (”Meie isa, kes sa oled”), where a mad father of a bizarre and non-communicative family has climbed a tree, or in ”Spirit” (”Vaim”), where the city government has mobilised the whole bureaucratic machinery to search for a new city spirit to replace the old one that had died. Love triumphs in this satirical buffo play too, when in the ”happy end” the aspiring spirit marries the mayor’s daughter. In ”Play” (”Näitemäng”), which gets off with the Hollywood-like dynamic action, the main character – a playwright – tumbles into a new situation each time he wakes up from his next dream or coma, until he becomes completely mad. The last and most surprising awakening takes him back to the morning of his fifth birthday, to his happy childhood when he still wanted to become a cosmonaut when a grown-up.

Kivastik’s humanistic sympathy towards losers is attractive and likeable, life sap is pulsating with full excitement and genuineness in his plays.

Asko Künnap, Jürgen Rooste, Karl-Martin Sinijärv, Triin Soomets, Elo Viiding. A Pack of Cards (Kaardipakk)

Näo Kirik, 2001. 56 cards.

A Pack of Cards looks like any pack of cards, only, it is polyfunctional. It contains the whole set of playing cards, but besides the traditional markings, each card carries a poem. This is an original anthology of the poetry of five authors; the format and function of a pack of cards should make it more attractive than an ordinary collection of poetry, bring it to the attention of the wider public and, hopefully, also affect the sales.

As a publication, A Pack of Cards has been beautifully designed, and the list of authors guarantees the quality of the anthology: they all belong to the top of modern Estonian poetry. Only Asko Künnap is a relatively recent newcomer, but his slightly futuristically and aestheticizedly written depressive city poetry with a global air is very convincing. Karl-Martin Sinijärv, who has written poetry for almost half of his lifetime of thirty years, surprises us with laconic aphorism-like verses, full of happy pessimism and witty linguistic play. Jürgen Rooste was given the Debut Award for the year of 2000. He is discovering the world – through eroticism as well, being witty and loud, and exercising graphic poetry and unusual page layout. The two ladies of this company are more severe and restricted than the others, concerning both the form of their poems as well as their emotionality. Triin Soomets is steadily following the model of great Estonian poetesses, her texts balance intellectuality and sensuality, her bright verses are charged with erotic tension; they are full of pleasures veiled with romantic mystery and unexplainable tragedy. Elo Vee, who writes free verse and uses ordinary spoken language, examines the time, everyday life and herself in the tense atmosphere of the turn of the century.

Typographically, a pack of cards is a very suitable format for a collection of poetry. The content of the collection seconds the idea and the company of authors ensures its quality and enjoyability. And something should be said for a good game of cards as well.

Hasso Krull. Cornucopia. A Hundred Poems. (Kornukoopia. Sada luuletust).

Tallinn, Vagabund, 2001. 180 pp

Modern Estonian poetry is inconceivable without essayist and poet Hasso Krull. Since the second half of the 1980s, he has published literary essays, introduced poststructuralist and postmodernist methods of analysing literature, and published a number of poetry collections that have often appeared to be illustrations to these theories. Krull’s poetry has mostly originated from secondary inspiration, it has striven for neutrality in phrasing and paragrammatical dialogue with other texts, rather reflecting the essence of language than the reality. His collections of poetry are integral and often devoted to a certain subject, as indicated by their titles, such as Swinburne and Jazz.

But the latest of them, Cornucopia, is a step towards plainness, although its texts carry the spirit of both modernist and postmodernist poetry. Being at the same time chrestomathical and varying in form, the poems delicately point at the inexhaustible possibilities of language and poetry, but they do not realise all these possibilities themselves. Metaphor is almost missing in these texts; intertextuality is much pronounced in poems inspired by the works of the beat-generation and Kostas Kariotakis. Compared with Krull’s previous work, the poeticising of details of everyday life and a complete free verse travelogue ”A Trip To the Country of Mari El” (”Reis Marimaale”) – broad and flowing like the Volga River along which the author travels in the poem – give the collection the air of newness. In this case, the whole is composed of two polarities – the aesthetic and the immediate reality. Or as Krull himself has said in one of his new poems, which is a dialogue discussing psychology of creative work: a book is, on the one hand, an artefact, but on the other hand, it is trivial everyday life which you need to be thoroughly familiar with.

Cornucopia is delicious and enjoyable, it is a subtle book, one of the best among the Estonian poetry collections of 2001. The reading of it is as exciting as drinking from the horn of plenty.

Tiia Toomet. School Tales from the Old Times (Vana aja koolilood)

Tallinn, Varrak , 2001. 64 pp

Tiia Toomet (1947) is mostly known as a children’s author, but she has published also a few collections of poetry and some short stories. “Vana aja lood” (Tales from the Old Times), published in 1983, became very popular among her about ten children’s books. In this book Toomet told about small things from her childhood, restoring the milieu and also the social atmosphere of those times.

School Tales from the Old Times has been written in the same key, but it is not a sequel to the previous book. Toomet’s ‘old times’ happened in the mid-century, when the grandmothers were children. “All school tales are a little similar and a little different,” begins the author, who started her school years in Tallinn in 1954, when Estonia was a part of the Soviet Union, textbooks told about good and happy life in the Soviet country, and the Estonian Republic and Christmas were the subjects people were not allowed to write about. Toomet, who has trained as a historian, approaches her subject rather as an ethnologist, not a writer, only the details, chosen from the child’s viewpoint, reveal that the children are the addressees of the book. Toomet tells us about the collective experience of the children of that time, describes the environment, things and characteristic situations. Since School Tales From the Old Times has been written in Estonia that is free from censorship (contrary to Tales From Old Times), the book reflects also those facts, which nobody could address directly in a totalitarian society. Under the overly ideologised surface of the school, the children lived their school life, which comprised of numerous traditional small matters. These are described in chapters “What the children were told at school in the old times”, “About the first school day in the old times”, “How children went home from school in the old times”, “How children joined the Young Pioneer Organisation in the old times”, etc. A practical description “how children went to school in the old times” has a humorous, but also an alienating effect today. Children started to learn the dual morale of the period from their early years. Toomet writes: “There were songs and poems about Lenin and Stalin, the leaders of the Soviet country, in the primer. But Grandmother said that he was the destroyer of Estonian state, Stalin was. But remember not to tell this at school.” The children of those times knew that they had to talk at school just as did the children in the primer. But it would probably need a long explanation to make the children of today see, why “Mother said that the teacher herself also celebrates Christmas, but she cannot tell about this to her pupils.”

Besides children, many adults also enjoy Toomet’s book. They recognise or rediscover things of their youth, as the book is richly illustrated with photos, drawings and pictures taken from schoolbooks of that time, and splendidly conveys the stereotypes of the period. School Tales of the Old Times is rather a historical book than a narrative, and as this, it is unquestionably the best.

Aidi Vallik. How Are You, Ann? (Kuidas elad, Ann?)

Tallinn, Tänapäev, 2001. 176 pp

Aidi Vallik (1971; she has published three collections of poetry popular among young readers) was awarded the main prize for her story How Are You, Ann? at the competition of youth literature in 2000. The choice of books for teenagers has always been scarce, thus the new work written by a teacher is a very welcome and surprisingly fresh addition to this area.

The target group of the book is children between 13 and 17 years of age. The author had asked her pupils at school what they would want to read about. The answer had been that naturally, about love and sex, and this is what the book is about. The main character is a fourteen-year-old Ann, who thinks that her mother is too strict and too unconventional at the same time. The mothers of her friends all seem to her much more normal. Unexpectedly she discovers her mother’s diary she had kept in her stormy youth before Ann had been born. The reading of the diary is a shock for the girl – she feels that her mother has lied to her all her life. Ann runs from home. But the joys of freedom are short-lived; her newly found girl friend is a thief, her first sexual experience teaches her that sex and love are two different things, and so on. Her money runs out, her new friends are selfish and cruel. Her prudent mother has foreseen all these happenings from her own experience and sent a guardian angel – an old friend from her youth – to look after her daughter. The happy end is in store. In a word, the book tells us about teenagers’ search for identity, their choice of lifestyle, and their relations with their parents. Since the author knows well the language, tastes, preferences, favourite stereotypes and problems of young people, the book has turned out to be immediate and without any overpowering moral. It is instructive indeed, but that is why it has been written.

Enn Vetemaa. Born to a Virgin (Neitsist sündinud)

Tallinn, Tänapäev, 2001. 436 pp

Since the time Enn Vetemaa (1936) came into literature in the early 1960s, he has written much in all main genres, still preferring prose and drama. His short novels written in the 1960s, and his plays have already become classical works of Estonian literature. Both have been translated into a number of languages.

Besides the absurdity of history and the paradoxicalness of life, Vetemaa has always been interested in the biological essence of human beings, related ethical issues, ethical relativity and the consequences of spoiling the balance. His characters, who face such problems and sometimes even pretend to be mad, often reach a crisis, which they cannot solve. The same happens in this novel.

Born to a Virgin reaches into global depths and discusses an actual subject – manipulation with genes and the cloning of man. An Estonian scientist of Russian origin Valeri works in a private fertility clinic. Trying to help the love of his youth, who has come to be treated in the clinic, Valeri by chance discovers how to use genetic and chromosome material to clone humans, but the method could also be used for virginal conception. Valeri reports his discovery to Russian intelligence service. A top-level game is initiated, where Russian intelligence service aims to destroy the reputation of Estonian state and American capital. The tests have stirred up the interest of Near East naftamagnates and other rich types who want to buy their doubles.

The action goes on in different countries and milieus and the book is full of unexpected turns. The author has always excelled in irony and humour, in creating paradoxical situations and finding elegant solutions to them; generally, the book is quite enjoyable. A number of scenes are witty and dazzling, but as the whole, the technical execution of the novel is uneven and slightly careless. The language of the author is sometimes too loquacious, and contains clichés. Aside these factors, the novel could well be compared with many international best-sellers, as the author has retained his skill in finding actual problems and funny solutions and the subject and scope of the novel are original.

Uku Masing. Poetry I (Luule I)

Tartu: Ilmamaa, 2000. 391 pp

Ilmar Vene. Defiant. An Attempt to Understand Uku Masing (Trotsija. Katse mõista Uku Masingut)

Tartu: Ilmamaa, 2001. 190 pp

If we wanted to call any person in Estonian literary history a genius, the first among such should be Uku Masing (1909-1985). Masing was a man of various interests who wrote prodigiously, and works on theology, history of religion and linguistics dominate among his mostly posthumously published books; still, his role as a poet is just as significant. Masing spent his whole life in Estonia, but during his lifetime, only his debut collection of poetry under an unusual title and dealing with unusual thematics for a young poet – Neemed vihmade lahte (Promontories Into the Gulf of Rains) – was published in this country in 1935. A selection from this collection was included in the anthology of poetry Arbujad (Soothsayers) of the authors from the generation that started publishing before WWII. Hints about modernism, and the striving to refine classical poetic forms and human perception dominated in the poems of this selection. Being a theologian, Masing was forced into internal exile in Soviet Estonia; his later collections of poetry were published abroad. In his homeland they circulated in manuscript, became cult books and in an indirect way influenced the whole literary process here.

The Uku Masing Board, managing the literary heritage of the poet, and the publishers Ilmamaa have started a massive project to make the whole of Masing’s poetry available in a set of six volumes. The first volume, published in 2000, contains the author’s so far unpublished cycle of juvenalia Roheliste radade raamat (A Book of Green Paths), which gives evidence of his early maturity; and reprints of his next collections Udu Toonela jõelt (Mist from the Toonela River) (1930-1943, first printed in Rome, 1974), Aerutades hurtsikumeistriga (Rowing with the Hutbuilder) (1934-1950, Toronto, 1982, 200 copies) and Kirsipuu varjus (In the Shade of a Cherry-tree) (1948-1949, Toronto, 1985), have all become bibliophilic rarities.

The task undertaken by the publishers is not easy, neither from a textological aspect nor concerning the content of the material. Masing’s manuscripts circulated in many different versions and his texts are full of neologisms and references to ancient and exotic religions, which all need plenty of commentary. Masing’s poetry has often been compared with T. S. Eliot’s (e.g., see Vincent B. Leich’s essay ‘Uku Masing Compared with Hopkins and Eliot, ELM no 9, Autumn 1999, together with poetry excerpts). Whereas Eliot wrote commentaries to his poems himself, we should consider all Masing’s essays and lecture notes as a key and aid to the interpretation of his poetry. Unfortunately, only a small amount of them is available in print. The mystical quest for God has been taken to be the leitmotif of Masing’s poetry, and indeed, all his work is steeped in religiousness. However, Masing is never traditional; his usually long and dynamic verses, which are as suggestive as a shaman’s chant, are characterised by intellectuality together with sensuality and are extraordinarily visual. His work is equally a prayerbook and a diary, an uninterrupted dialogue with God, but also a prophet’s words meant for mortals; in his abundance of associations, Masing synthesises the whole poetic experience of both the Orient and the Occident. The mysterious charm of Masing’s poetry has encouraged succeeding generations to read it and try to understand it.

Uku Masing and his work have provoked a large amount of metafiction, mainly in the form of memoirs or discussions of certain problems or events. The author of a number of essays, and the translator of ancient authors, Ilmar Vene, has written the first integral book discussing Masing. We cannot find much biographical data in the book, but writing a biography was not Vene’s aim; instead, he offers a convincing introduction into Masing’s intellectual world. The author’s opening sentence says: “Going towards Uku Masing means taking a detour,” and Vene outlines Masing’s intellectual portrait against the background of the great figures in European culture, mainly Rousseau, Tolstoy, Nietzsche and Paul Tillich, critically stressing their similarities, and noticing their differences and peculiarities as well. Masing absolutely opposed authority and Western culture, just as did Rousseau and Tolstoy, for whom the development of civilisation led it away from God. Masing related to Nietzsche through the cult of superman (Übermensch), unexpected at first glance. However, Masing, too, saw man as a weak and helpless creature, an earthly failure of divine creation, who intellectually had to overcome his state. Masing remained a Christian, although unconventional even in his Christianity, as his special “favourites” were the Old Testament Books of Job and Ecclesiastes. He saw an alternative in Buddhism and he was especially keen on religions of primitive peoples and the mythology of ancient Sumer. Vene points out Masing’s aversion to all hyped issues, but he admits that Masing appreciated Hermann Hesse and Rabindranath Tagore, some works of whom he translated into Estonian.

Vene’s analytic and comprehensive essay discusses many so-far seemingly mysterious aspects of Masing’s life as a scholar, spontaneous essayist and poet, and makes him comprehensible for us. Maybe we can discern the prophet in Masing’s fondness for Jewish prophets; his state of being an outsider, his Übermenschlichkeit and his hostility towards everything Indo-Germanic, which can be sensed in his texts are explained. Finally, Defiant presents us with a portrait of a scholar as visually perceptive as we can find in some of Masing’s own treatises or poems – a portrait where both the spiritual and human essence are in good balance. Vene shares a memory of Masing – him standing in a somewhat stiff posture, with his side towards the class, delivering his monologue-lecture; his limply hanging arm symbolising the earth’s gravity, and the smoke of the cigarette between his fingers rising, as the symbol of all aspirations, towards the eternal world.

Estonian Identity and Independence (Eesti identiteet ja iseseisvus) Compiled by A. Bertricau

Tallinn, Avita, 2001. 317 pp

Both the creation of the Republic of Estonia in 1918 and its restitution in 1991 stemmed from the enlightening and National Romanticist ideas of the 19th century, being their after-effects. Therefore, national identity, which was the prerequisite for emerging statehood, has always been taken to be based on Estonian-language schools and culture. Estonian historical research, as much as it has been possible to carry it out independently of political powers in Estonia, has so far not paid much attention to national identity. Different aspects of this subject have only been sporadically discussed in research concerning history and cultural history.

As a book, Estonian Identity and Independence is a pioneering work, and can be even more appreciated, as it has been created from a certain distance. The initiator and compiler of this work, which draws together articles, conversations, interviews and subjective opinions, is the French Ambassador to the Republic of Estonia, Jean-Jacques Subrenat, who uses the alias A. Bertricau. The collection, introduced by a salutation to the French spirit written by the President of Estonia Lennart Meri, was from the start aimed at the foreign reader, as stated by the compiler in the foreword: “Each foreigner, who is interested in Estonia, has to ask himself some questions: Which are the hypotheses explaining the origin of Estonians? How have the inhabitants of this country preserved their identity while passing through the labyrinths of history? How has this identity changed and developed and what have been the factors affecting these processes? Under what circumstances occurred the proclamation of independence, the destruction of it and the restitution of it – all in a relatively short period of seventy years?”

These questions are discussed and examined in this book by twenty-five Estonian intellectuals, among whom are historians, journalists, politicians and writers. This is a concise and sometimes polemical overview of Estonian history and mentality, and even of the genetic origin of Estonians, which questions several national myths. More recent history has been presented through personal experiences and subjective observations concerning the preservation of national identity in exile and during the periods of Soviet power and independence.

The publishing of the collection Estonian Identity and Independence is of crucial importance for present-day Estonia, which aims to regain its position in Europe. Firstly, it gives a well-grounded explanation to foreign readers about how important historically their national identity is for Estonians, although it is very often considered as an anachronism in this era of general globalisation. Secondly, the book is just as important for Estonians themselves, as the articles by historians Margus Laidre and Ea Jansen, but also some others, question national myths which previous historical discourse has cultivated for a number of reasons. We cannot dismiss the idea proposed by historian Andrei Hvostov, claiming that the whole national identity is based on a myth. The polemicity, and even provocativeness, of the book only adds to its value, inspiring us to take a fresh look at these matters.

Ene Mihkelson. The Scales Do Not Speak. Selected Poems from 1967-1977 (Kaalud ei kõnele. Valitud luuletusi 1967-1997)

Tallinn, Tuum, 2000. 299 pp

Although Ene Mihkelson’s (1944) voice has been heard in Estonian literature for over thirty years, her first book, a collection of poetry Selle talve laused (The Sentences of This Winter), was published only in 1978. The work of the rather saturnine poet with an untraditional poetic voice, who delved deeply into paradoxes of history, contained an indistinct and hard to define danger to the totalitarian regime, which also resulted in her falling behind the vigorous poetry scene legendary in the Estonian literary history of the sixties. But maybe this is the very reason we can apply the aphorism – things that do not kill you make you stronger – to Ene Mihkelson. Without paying homage to any fashionable trends, Mihkelson’s poetry has reached the focus of Estonian literature in the 1990s, and her voice sounds even more strongly against the background of the fashionable trends of the turn of the century.

The Scales Do Not Speak is a selection from her work of thirty years and from her ten published collections. This is a real masterpiece, made even more impressive by Naima Neidre’s congenial illustrations. The precise selection made by the poet herself gives a good idea of how she stayed true to once common poetic forms, and of the changes the content of her work has undergone over time. Concerning form, this change can be seen in her texts that lack rhythm and rhyme, and are broken into stanzas only in accordance with the ideas expressed in them; the deliberately neutral wording sometimes resembles a philosophical, but image-filled treatise. Personal history and family saga, as well as the history of her people, inform the content of her poetry, and the reader is struck by her ambitious aspiration to find the bottom of all things, very often aided by paradoxical images. The development of Mihkelson’s poetry, often described as intellectual and melancholy by critics, has proceeded towards openness and broadening; her technique of allusion has been enriched by influences from Estonian literary classics and core texts of world culture.

Her texts seem to be directly generated by time; the poet is only a medium, whose role is to “compress Time into an exploding lump”. Contemplating the paradoxes of origin, descent and memory, and searching in the ‘backyard’ of consciousness and national myths for newer and newer hidden meanings, some of these ‘exploding lumps’ can have the effect of a real poetical shock – like the squirt of blood from a frog jumping through the blade of a scythe in one of her poems. This could well be the reason why Mihkelson’s poetry has been characterised as cruel and the expression ‘sado-maso history’ has been used to denote her poetical depiction of history. But her work is no crueller in its images and its striving for deep understanding than the whole of Estonian history has been.

Mehis Heinsaar. The Snatcher of Old Men (Vanameeste näppaja)

Tallinn, Tuum, 2000. 155 pp

The work of a young student, Mehis Heinsaar, found renown even before he published his first book. His short story Liblikmees (Butterfly Man) was chosen for the Fr. Tuglas Short Story Award in 2000. It was a story about a man who releases butterflies while in a state of spiritual agitation. Since this occurs in a circus, where tricks are a must, only the man’s empty suit after the performance at the climax of the story indicates that something beyond reality has occurred. Heinsaar’s first book contains sixteen short stories in three cycles – Teed ja kohtumised (Roads and Encounters), Mees, keda armastasid tuuled (A Man Who Was Loved By the Winds) and Mälestusi elust (Reminiscences of Life), and shows the pen of a real master.

Heinsaar may notice details, but he does not heap them abundantly; his language is quite concise and his stories seem to be rather simple and ‘ordinary’ at first glance. But their realistic beginnings are soon twisted into fanciful, even absurd and surrealist, turns, which the author narrates in a natural and matter-of-fact tone, as if fairy tales and all kinds of transformations were a natural part of our everyday life. For this reason Heinsaar’s stories have been classified as magical realism. The title Kuidas surm Mirabeli juurde tuli (How Death Came to Mirabel) could well be attributed to Marquez. Although Heinsaar’s stories are often set in a recognisably Estonian setting, the specified setting, either a circus, a park bench, a student’s room in a slum or some other, has been put in to make sure that the stories are believable. Many of these stories could well take place anywhere in the world, and in some cases we can recognise the author’s source of inspiration in world literature. A cat who dictates stories to a writer seems to be a close relation of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s Murr the tomcat.

The vigorous opening story of the collection, titled Tere (Hello), lends a playful tone to the whole book. Here a pedantic and spiteful old man sits on a park bench beside a strange schoolboy, whose impudence he decides to punish. He grabs the boy and demands to be taken to the boy’s parents. But when the boy opens the door of a dilapidated slum house, the old man finds a lawn or a park inside, where a large number of similar old men are playing tag and draw him into pursuit. The transformation in space marks the end of the story. The last story of the book “Kohtumine ajas” (“Encounter in Time”) is a much more depressing, hallucinatory tale about how a stinking hobo, a onetime writer, rapes a girl on a park bench, taking her for the love of his youth. This transformation in time, obviously alluding to Nabokov’s Lolita, was written in the same key of poetical realism as the book’s other bright and entertaining stories. We could even find a kind of moral in ‘Encounter in Time’, but Heinsaar’s stories can simply be read and enjoyed, in the way the author enjoyed writing them and playing with fantasy.

Estonian Literary History. (Eesti kirjanduslugu) Epp Annus, Luule Epner, Ants Järv, Sirje Olesk, Ele Süvalep, Mart Velsker.

Tallinn, Koolibri, 2001. 703 pp

The previous Estonian academic literary history was published in 1965-1991, in a set of seven grey brick-like volumes with a total number of pages amounting to more than 4000. This very informative collaboration of many authors still bears the ideological stamp of the time of its publication; for example, the whole of Estonian exile literature was left out. For this reason the work is hopelessly out of date, at least according to ideological and artistic judgements. Research that has focused on different periods or authors, and school textbooks that have been published since, cannot give a comprehensive discussion of Estonian literature. Considering this, we must admit that the new Estonian Literary History, a co-operative effort of six lecturers of the Chair of Estonian Literature at the University of Tartu, is an indispensable work for all who study, teach or simply enjoy Estonian literature.

This work, condensed into one large volume, begins with the first chapter written by Ants Järv, offering a brief glimpse into early Estonian history and folklore, continuing over the earlier didactic and edifying church literature towards the sources of national movement in the 19th century, and reaching the appearance of professional literature at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. Ele Süvalep examines the attempts to take Estonian literature into Europe at the beginning of the 20th century, and poetry and general literary trends up to the beginning of WWII. Epp Annus discusses pre-WWII and modern prose trends. Sirje Olesk and Mart Velsker have jointly examined the post-WWII exile literature and also post-war poetry. Luule Epner has examined drama of all periods and some authors of modern prose. The authors have boldly taken the risk in the face of Time – the greatest judge – of including in the book many young authors, who have only begun their literary career, confirming the freshness and contemporarity of their approach. On the other hand, a number of authors, who had been represented in the earlier literary survey, have now been left in the background or have even been entirely left out; this fact has already provoked criticism of the authors of the present volume.

The omissions have their reasons. The authors have attempted to examine Estonian literature as a process which conditioned strict selection and the inclusion of only innovative authors and works. Therefore the present literary history mainly stresses thematical and also period outlines; portraits of individual authors take a back seat.

Since the methodological basis and model for the authors originates from Tiit Hennoste’s series of lectures Hüpped modernismi poole (‘Leaps Towards Modernism’), held at Helsinki University, Finland, and published as articles in the journal Vikerkaar, we could say that in some sense we have been presented a teleological approach to Estonian literary history. But, whereas Hennoste examined the history of Estonian literature as a continuous development towards European modernism still in progress, the authors of the present literary history consider postmodernism and other new, related trends as the main contemporary goal of literature.

The discussions and debates among literary theorists provoked by the Estonian Literary History accompany any innovative approach. This beautifully executed volume has in any case become a necessity for everybody who deals with Estonian literature.

© ELM no 13, autumn 2001