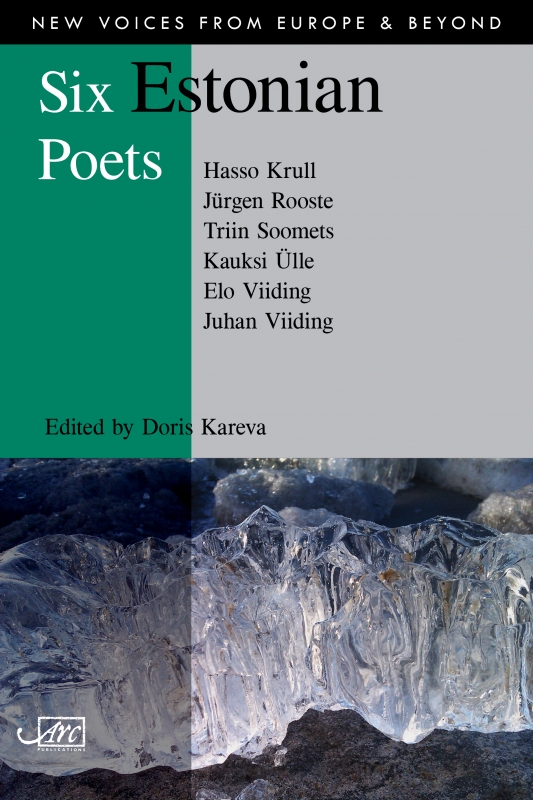

When writer and literary critic Igor Kotjuh posted on his Facebook account the top ten events in Estonian literature in 2015, one of them was titled: “the year of translation anthologies”. According to Kotjuh, at least six different anthologies or special publications of Estonian literature were published in other languages. Two of these were released in English – the online magazine Words Without Borders published a special edition on Estonian literature featuring the works of nine different authors, and British publisher Arc Publications released a sampling of Estonian poetry titled Six Estonian Poets. The latter is no ordinary work thanks to the fact that it was composed and edited by Doris Kareva (1958) – one of the most popular poets in her homeland.

As the compilation’s title declares, its selection includes the works of six Estonian poets. Five of them are active to this day, and each has played a very significant role in contemporary Estonian poetry. Although the selection is not at all extensive, the main trends of newer Estonian poetry nevertheless stand out. Three of the authors were born in the 1960s, and thus it is no coincidence that the start of their respective creative paths coincides with the restoration of Estonia’s independence. Even so, temporal coincidence does not necessarily mean an overlap in terms of content. Poetry may certainly flow along with an era during turbulent times, but it still embodies precisely that register of language, in which one can speak on timeless topics. Thus we don’t, for instance, encounter any overt social tones in the works of Triin Soomets (1969). Some may certainly regard her as a feminist author, as she speaks from the female position in many of her poems. Still, if we were to tie Soomets’ works to some greater conceptual trend, then existentialism might be suitable. She is intrigued by the eternal tensions in human relationships, as well as their reflections in our own consciousness; a recording of them that is simultaneously as emotional and as precise as possible.

Although Hasso Krull (1964) has written quite many pieces of social critique over the years, his creative reach is too broad to be exhaustively classified in one or two sentences. Krull’s poetry is characterised by his generous use of references, the placement of singular texts in a broader context, and the connection of ideas to other texts; all resulting in personal experience being joined with some greater whole and a quest for wider unity. While French post-structuralism and post-modernism had a more extensive influence at the beginning of Krull’s artistic career, his interests have since focused on heritage, mythology, and folklore, not to mention nature. Spiritual kin to Krull are the works of Kauksi Ülle (1962), which likewise derive from folklore and Estonian nature but are more specific in terms of location, focusing on Võru County in Southwest Estonia. Kauksi Ülle indeed writes in the Võro language – not in Estonian; her inspiration springs from local beliefs and Estonian runo singing (regilaul), through which she is best able to describe the perseverance of old traditions and trials in the crosswinds of history.

Looking at the collection’s two authors born in the 1970s, the style of their talent is characterised by a different kind of mind-set: one that is much more active; an attitude that echoes social events and moods with greater immediacy. The collection’s youngest author, Jürgen Rooste (1979), is probably the frankest poet of his generation. Rooste is a romantic rover of city streets, who – in addition to his self-sardonic confessions and love for women, beatnik literature, and music – perpetually criticises his country’s politics and the Estonian mentality. Elo Viiding’s (1974) criticism delves even further, uncompromisingly detailing the inner logic and contradictions of social norms and ideals. Once again, it would be too restricting to label Viiding’s work as feminist, since she is interested not only in women’s position in society, but also in how all kinds of positions are formed and adopted in the first place.

However, standing in an echelon of his own is the collection’s sixth author – Elo Viiding’s father Juhan Viiding (1948–1995). One could say that he doesn’t stand apart from the other poets, but rather above them. The late renowned poet, actor, and singer has become an Estonian legend in our time. This could partly be due to the fact that Viiding was certainly a colourful character, and was known for his witty social spirit. Since Viiding was an actor, he was unsurpassable in performing his own texts, especially since many of his poems were seemingly written to be sung and read aloud. Viiding’s personality and fate added a dramatic, “larger-than-life” shade to his works. Most Estonians are familiar with his lines: “What is the poetry of a poet? // To think upon life / and something else unknown yet.” It is this “something else” that formed the core of Viiding’s poetry – an obscurity that is reluctant to yield to formulation in words; that entices and challenges life. Viiding accepted the challenge and became one of the most outstanding experimenters of Estonian poetry. His most famous experiment was named Jüri Üdi. It would be hard to claim that Üdi was Viiding’s pseudonym – Üdi’s works were far too independent. Üdi was like a personality in and of himself – a sarcastic and artistic figure, for whom language was no longer a tool of expression, but rather the manner of it. Üdi loved to switch linguistic registers and meaningful tones within the bounds of a single poem, as a result of which quite many of his texts come off as simultaneously humorous and melancholy. There was always seriousness in play, always play in seriousness. The extent to which the severity of Viiding/Üdi’s poems conflict with the inner mobility of their message is remarkable. The sense of freedom in Viiding’s poetry no doubt also cast its own shadow over his unexpected death – he personally would hardly have treated his posthumous stardom with saintly seriousness.

Juhan Viiding was a true linguistic master who brought the balance between a poem’s polished form and the density of its message to perfection. He found in the Estonian language the exact rhymes and phonetic compositions which, when crafted into poetry, cause the reader to feel that the words being used were invented precisely for that text. Estonian language and Estonian poetry have not been what they were since Viiding’s death, and his works had a more-or-less direct effect on nearly everyone who grew up to the tune of his words.

Jan Kaus (1971) is a writer and musician. He has published five novels, and has also authored poetry, essays, novellas and miniatures. In 2015, Kaus’ novel Mina olen elus (I Am Alive) and miniature collection Tallinna kaart (A Map of Tallinn) won the Cultural Endowment of Estonia’s Award for Prose.