When I was asked to write about the five Estonian short story writers I enjoy the most, I unconsciously wondered: based on what criteria? This article will be translated into English, and will introduce Estonian short stories and their authors abroad. But is there any point in writing about those whose works, for the most part, don’t differ from what already exists in the world, such as the Estonian classics who certainly don’t pale alongside global literature, but who, in fact, offer nothing novel? Thus, I attempted to spend time only on the authors whose writing, form, or style are somehow (very conditionally) special and unique to us as Estonians. Luckily, there are many of them.

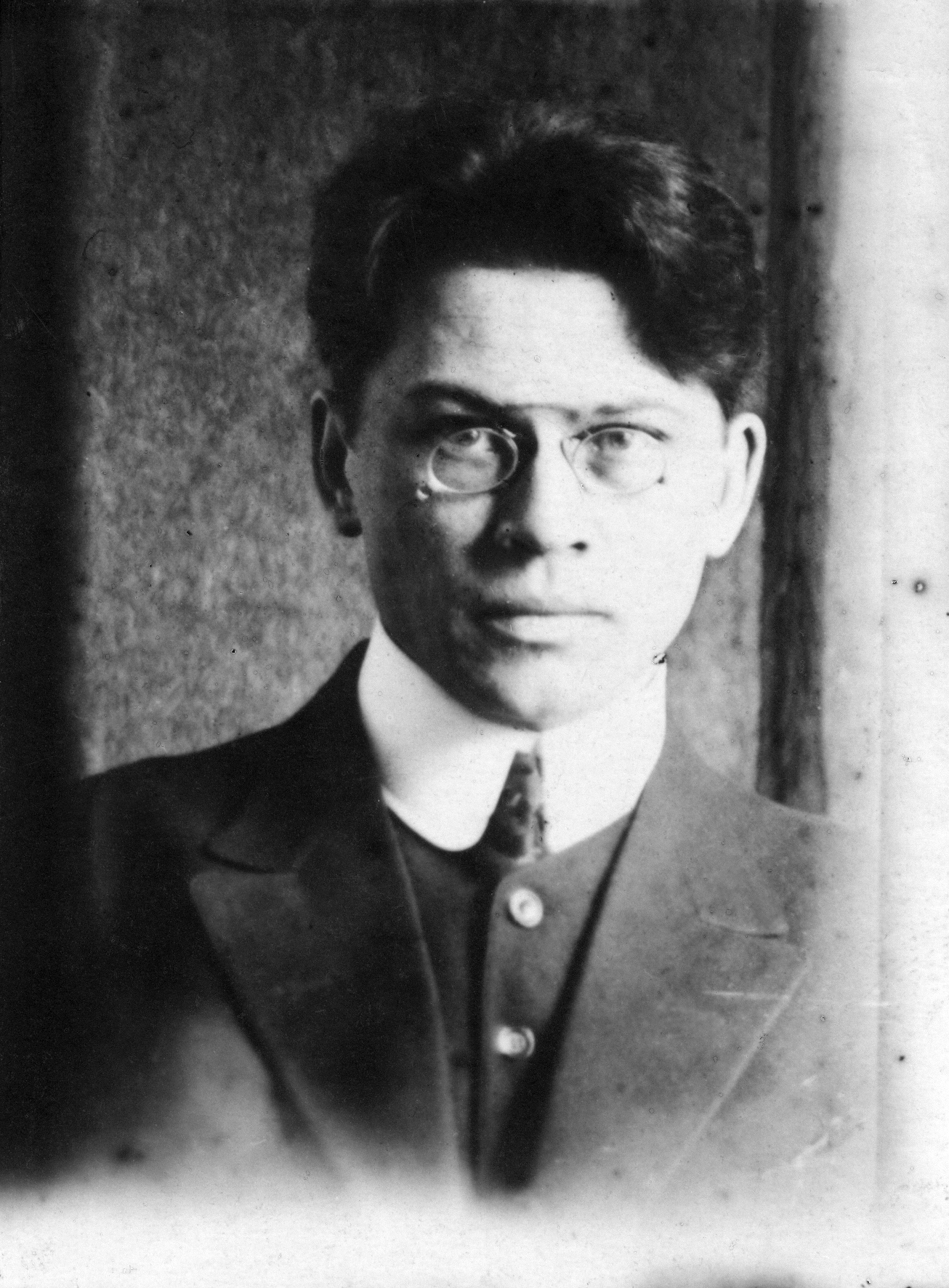

If one is to speak about the Estonian short story, the history of which extends into the early 20th century, then it’s impossible to overlook its inarguable luminary and father, Friedebert Tuglas (1886–1971). Tuglas’ best-known short story “Popi and Huhuu” stands apart from both Nordic and Soviet short fiction. Written after World War II, it tells of two animals abandoned in a home. After their owner fails to return, the aggressive chimp and small dog start living their own lives in the shuttered apartment. The monkey escapes his cage and starts to play the role of master. Everything changes, degenerates, and crumbles. Although the chimp is spiteful and sadistic towards the little dog, he becomes a replacement for their owner all the same, and can even be loved. This is perhaps the most dismal and grim twist to the story. The work’s political subtext was immediately recognized, and can be applied to any leaderless or godless society. Philosophically, “Popi and Huhuu” is definitely world-class literature.xRegardless, many contemporary critics believe that Jaan Oks (1884–1918) was Estonia’s best novelist to date. Oks sent his works to Tuglas (though they allegedly never met in person), who edited and then published them.

However, reviewers at the time wrote that it would be better if Oks were to rot alive… And so things went, in part: Oks died of tuberculosis of the bones. His writing is hulking and possesses an immense, intense energy. It seems to scorn everything and everyone, whether the subject is nature, women, reproduction, lust, life, or God himself. Oks was extremely self-serving, exceptionally sensitive to life events, and petulant; he was incapable of understanding how life could be so cruel. All the same, Oks’ genius lies not in his views, but rather in his style and the superior outbursts of his writing, creating a trance that certainly exceeds the bounds of ordinary prose. His works are part poetry, and contain something unique to him alone, something striking, writhing, and screeching. It’s occasionally difficult for the reader to follow what is actually taking place in the storyline, and who is who. Everything melts together: the plowman turns into the horse, then the horse into the plowman, after which the forest and the sky speak, and by the end of the novella, the reader feels as if he or she has stepped off a merry-go-round and, in addition to dizziness, the rider has received a proper beating as it spun. Oks also wrote more sedate and comprehensible stories, but his depiction of human life is always futile, oppressive, and distressing. The ideal in Oks’ worldview was the triumph of pure sensibility, something that is, alas, hindered by endless sexuality, a woman, pain, and death. Comparing Oks to a foreign writer, Knut Hamsun and his work Hunger come to mind.

Viewed as a whole throughout its history, Estonian short fiction has certainly been heavy, growing slightly lighter and more cheerful only over the last few years. The Soviet occupation left its mark, as did the building of both Estonian republics, along with the woes and difficulties that accompanied the process. Much has been borrowed from Scandinavia, the humor is bitter or hidden and somewhat British, and merry storytelling is rarely encountered. The Estonian short story is a bonanza for the depressive reader.

During the Soviet occupation, when publishing was rather problematic, novels were often turned into short stories; nowadays, the opposite is sometimes the case. To speak briefly of Soviet-era Estonian short stories, its distinctive archetype is certainly Toomas Vint (1944). Vint was perhaps the only Estonian short prose author who, in his own unusual way, did not try to be superior to the Soviet system as most strove to do, but to aesthetically deny it altogether. Aesthetics was precisely what disarmed the censor. His works resemble a formerly enchanting, but now forgotten park in an Orwellian totalitarian state that lacks any trace of beauty. As the antipode to those years (and even in today’s context), Vint’s man-and-women dramas are very individualistic. There is no room for a foolish society or secondary factors: no room for isms or ideologies. It is above all Vint’s ability to maintain and convey a lost harmony that makes him the king of occupation-era Estonian short fiction.

For the true connoisseur, I would recommend Jüri Tuulik (1940–2014) from the tiny island of Abruka, and particularly the works published over the last few years of his life. His writing is somewhat choleric, comprehensible but sometimes inexplicable, and exceptionally personal. A kind of hopeless farewell echoes from Tuulik’s writing. The reader feels like a bird soaring above a stormy sea, and the text doesn’t apply direct pressure to the soul, as is common in stories of inescapability.

Like many Estonian short story authors, Tuulik writes in his own space: the setting of his stories is a tiny island recognizable to Estonians, but at the same time, this does not disturb those unfamiliar with such places. On the contrary! In spite of the details, the author created his landscapes in a universally intelligible manner. And although nature, the sea, and the sky play an important part in his writing, the plots could also be set in a coastal Scandinavian village, or anywhere that is windy and populated by seagulls… Tuulik’s distancing and farewell makes specific sites, nature, and life itself abstract. The world is like a decoration, of which one cannot and will not let go. Although his early writing is humorous and folksy, and his later works do not go beyond that, they do not offer frank truths in a verbal context. Rather, the stories can be compared to paintings. Tuulik’s best-known work is the short novel Crow (Vares), which was published in the late 1970s, has been reprinted thrice, and has been translated into several foreign languages, including English. A few of his better short stories and novellas have been compiled in the collection A Lone Bird Above the Sea (Üksik lind mere kohal, 2002).

Another one of Estonia’s more intriguing contemporary prosaists is the little-known Agu Tammeveski (1951). Immediately after entering the literary scene in the late 1980s, his novella Air (Õhk) received the prestigious Estonian cultural journal Vikerkaar’s annual prize. Tammeveski’s characters are primarily men whose struggles and senses of aspiration have reached a breaking point, where nothing has meaning any longer, a point which is often also darkened by a failed relationship. What makes Tammeveski’s writing exceptional is that his existentialism is always distant; it lacks sadness. It’s just the way things are…

Literature, or creativity in general, rests (at least to a certain extent) upon something that might be called the universal. It is the point from which every writer or artist (or human in general) departs, consciously or unconsciously, even if that individual proceeds with the intention to destroy, demolish, or renew the concept of humanity. Yet, Tammeveski’s appeal lies in his unnerving originality, where the writer’s worldview and foundation are anchored in something entirely different: not ruling out the expression of humanity, but seemingly passing it by. Thus, immorality is not inherently abnormal, but due to something far deeper. Tammeveski’s texts can’t be compared to those by authors who probe limits, because for him those limits apparently don’t exist. There is simply… air. Stylistically, he writes with incredible clarity, and the text is gossamer, almost breathable. But at the same time, it isn’t dry, which is generally expected of the prosaic style. I believe that in the 1980s, together with Tõnu Õnnepalu and Juhan Habicht, Tammeveski smashed the former (and especially occupation-era) framework of the Estonian novella. A satisfactory overview of his writing can be found in the 2003 Estonian-language collection A Long Sprint. Stories from 1986–2001 (Pikk hoojooks. Jutte aastaist 1986–2001).

As for contemporary authors, I would firstly highlight a writer named Mudlum. Although her debut on the literary scene came just recently, several of her short stories return to the Soviet era and, like many authors, she is often very personal in her storytelling. Memories of her childhood and youth are told relatively directly and without the use of any tricks. Space and details are of great importance in Mudlum’s stories, creating an atmosphere where nothing special seems to happen, but where the scene itself is a part of the message. Her lexicon is extremely rich and sometimes even overwhelming, recalling classics such as Gustave Flaubert and his Salammbô. The language Mudlum uses is beautiful. At the same time, the writer is more than a describer of situations: in many of her short stories, she has the densest concepts and is the most philosophical of contemporary Estonian short prose writers. Mudlum’s inner dialogue is outstanding and, at times, she is even capable of being more masculine than Estonia’s male writers. In truth, her writing touches all ends of the spectrum: her diapason is extremely wide. In addition to melancholy, Mudlum displays sharp but all-the-more hidden humor: life’s twists, turns, and distancing are all doubted in a particular way. She loves the individual above all, and we encounter little if any relationship drama.

Relationships are a part of being human, but in no way a free-standing fire. Generally, her narrator or protagonist provides something bright and positive – or at least something ironic – to go with the typical despondent mood. Mudlum doesn’t give up… To date, she has published two collections of short stories: A Serious Person (Tõsine inimene, 2014) and A Bird’s Eyes (Linnu silmad, 2016).

I’ve covered merely a tiny fraction of Estonian short-story writing here, and I certainly don’t possess a full overview of everything. Estonians write voluminously (or even awfully voluminously), and as such, I’ve inevitably overlooked a number of authors; there simply wasn’t enough space.

*

Mait Vaik (1969) is an Estonian writer and musician. Vaik has played in several legendary Estonian rock bands, such as Vennaskond, Metro Luminal, and Sõpruse Puiestee. He is still active in the latter. Vaik has written lyrics (and sometimes also music) for several of the aforementioned bands. His first book, Everyone is Always Right (Kõigil on alati õigus, 2012), was indeed a collection of lyrics and poems. A year later, he published his first collection of short stories, Juss and Brothers (Juss ja vennad, 2013), which has sometimes also been classified as a short novel. Currently, Vaik is regarded as one of Estonia’s most

intriguing short story writers, and has published two collections: Clock-Out (Tööpäeva lõpp, 2014) and Without Repentance (Meeleparanduseta, 2016). His story Purity (Puhtus) received the Friedebert Tuglas Short Story Award, which is one of Estonia’s most prestigious literary recognitions.Reviews of Mait Vaik’s books:

Clock-Out: “Vaik possesses the ability to create impressions and moods. And when he feels that one style or perspective is starting to wear itself thin, he is capable of switching it quickly. This especially stands out in the collection’s only narration, “Man”, which tells the story of a man and his loved ones through various registers and approaches. The author’s interest in a range of storyteller personae can be seen in this particular piece, as well as in a few others: on a number of occasions, he turns to the Estonian language’s informal “you” form, which is relatively unusual in Estonian literature. This is a good way to get nastily under the reader’s skin.” Peeter Helme

Without Repentance: “Over and over when reading the prose texts in Mait Vaik’s collection Without Repentance, you’re astounded by how powerful good literature can be: such literary greats as Mann, Dostoyevsky, Bunin, Kafka and, of course, Vaik himself (as a writer of rather unparalleled lyrics) unconsciously run through your mind. However, with the publication of his book Juss and Brothers, the prose-Vaik swiftly rose to the level of the lyrics-Vaik and the latter’s very recognizable style.” Paavo Matsin