Published in 1935, I Loved a German (Ma armastasin sakslast) was the seventh novel written by the Estonian literary classic A. H. Tammsaare (1878–1940). Tammsaare had already risen to the status of living classic after completing his chief work, the five-part Truth and Justice (1926–1933), and his following books aroused increasing public attention. One year earlier, in 1934, the author had shocked readers with his novel Life and Love (Elu ja armastus): the book’s eroticism and its protagonist Rudolf caused such outrage in some circles that there were calls to ban it entirely. I Loved a German brought a different kind of surprise.

In a way, the issuing of a state commission can be seen as Tammsaare’s motivation for writing the novel: Estonian authors were encouraged to create a “positive university-student character” as part of the Estonian Book Year celebrations (1935 marked 400 years since the publication of the very first Estonian-language piece). Tammsaare flipped the call on end, writing a novel about an identity crisis and love’s possibility or impossibility instead.

The novel’s protagonist is a student corporation member[1] named Oskar, who has quit his studies. He is boarding at a house where the matron, in addition to showing fondness for her husband and children, is highly fond of meddling in her tenants’ lives. A down-on-her-luck Baltic-German girl named Erika works as a nanny and teacher for the children. Oskar asks Erika out on a date, and the relationship, which is intended just for fun at first, quickly transforms into an intense love for both.

Thus, on the one hand, I Loved a German is a love novel in which Tammsaare handles a theme that is recurrent in his works: the possibility of love and the complexity of male-female relationships.

On the other hand, the novel deals foremost with Oskar’s identity as an Estonian. When the young lovers’ relationship has developed to a certain stage, Oskar pays a visit to Erika’s grandfather, the old baron. All of the instincts a descendant of peasants might be expected to possess surge forth when Oskar meets the former manor lord: he calls Erika’s grandfather “Sir Baron” and speaks in German, even though the man also speaks Estonian. At one point, Oskar becomes troubled by the thought that he doesn’t truly love Erika for who she is, but rather as a German; as an aristocrat; as the master who has ruled Estonia for centuries. Thus, figuratively speaking, he fears that he loves Erika’s grandfather more than he does the girl herself. When the old baron asks Oskar what he has to offer his granddaughter, who can at least claim a long and noble heritage, the boy is at a loss for words. He starts debating his own nature and that of Estonians, and just cannot seem to put his finger on where his own worth might lie.

The novel climaxes with a scene in which Erika proposes that Oskar run away with her, thereby compromising her reputation, all in the hopes that afterward, her grandfather might consent to their marriage. Oskar refuses because he doesn’t want the old baron to think he, Oskar, is a scoundrel. Yet, to Erika, this signals the weakness of the boy’s feelings for her. Critics have traditionally regarded the scene as proof of Oskar’s spinelessness: he is afraid to take a decisive step, and loses his beloved as a consequence. Nevertheless, at the end of the novel, the author praises Oskar for this very act through the baron’s words: “I should have known all along that you truly are a proper Estonian man, with the heart of a proper Estonian man, the likes of which I’ve seen scores of in my lifetime.”

In any case, the situation is inescapable from Oskar’s point of view: no matter what course of action he takes, running off with Erika or not, he will still be making a mistake. For by compromising her reputation, he truly would be acting like a scoundrel. He is only able to prove his love by not proving it. Paradoxical situations such as these are common among Tammsaare’s works, conveying the author’s distinctive understanding of the complexity of human relationships, which was expressed earlier as “failing to escape fate”. Conscious choices often seem to have no impact on what ultimately transpires.

Alternately, if Oskar had found an opportunity to marry Erika, then would their love have lasted? One question that Tammsaare puts forth in his novel indeed concerns the “sociality” of love: specifically, he believes that love does not exist in a vacuum, but in a society filled with different customs and prejudices. Tammsaare demonstrates that a great and pure love can certainly exist, just not in the ordinary way. Love always clashes with societal relationships and expectations in everyday life. Given how many marriages there are between partners of different ethnic backgrounds these days, the novel is inarguably still a topical one. It explores, among other things, how much dissimilar cultural backgrounds may affect love, as well as what it means for a partner to feel him- or herself to be of lesser worth. Tammsaare’s male characters tend to fall in love with women on higher rungs of the social ladder. On the one hand, the author takes note of women’s inspiring and often redeeming influence on men; on the other, he never allows these societally unequal affections to develop any further than the platonic phase. Tammsaare’s characters frequently fall short of true love, never to be achieved fully.

Another central issue in the novel is Oskar’s sense of uncertainty as an Estonian. Tammsaare used Oskar to voice strong criticism of the Baltic-German-influenced student corporations, which he believed cultivated intellectual vapidity. Read parallel with Tammsaare’s opinion pieces published in the 1930s, it is clear that the author also used the protagonist to criticize the upstart mentality and the loss of oneself in endless entertainment. The novel presents questions of principle: do Estonians possess the inner fortitude to be independent? Are Estonians a unique and self-confident civilized nation, or do they wish to be imitators, out of convenience? Tammsaare believed this was a critical question from the standpoint of national perpetuation, and the criticism he aims at Estonians’ weakness of identity in fact reflects his deep worry about the continuity of his ancient people. As a result, I Loved a German can also be seen as an existential novel, because Tammsaare explicitly addresses questions of national existence.

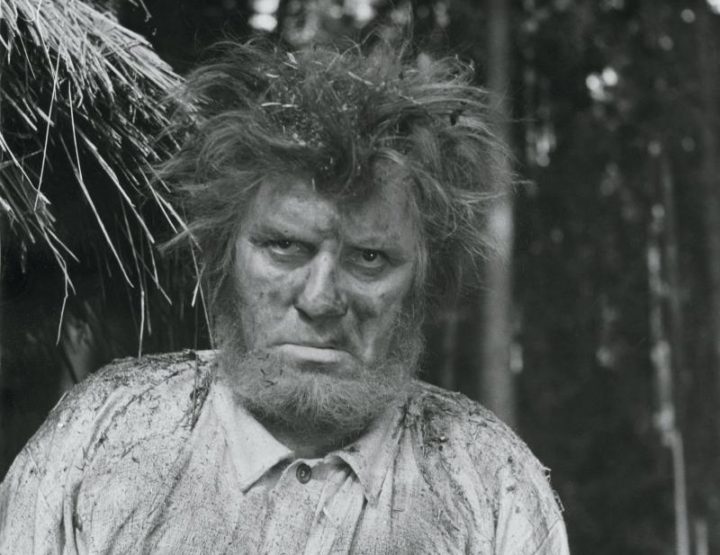

Oskar represents a typical first-generation urban scholar who has roots in the countryside. He no longer feels that he is a peasant, but neither is he a city dweller yet. Situated between two worlds, Oskar is thus a symbol of man tending to lose himself in the modernizing world, regardless of nationality. Both Oskar and Erika are characters who have lost the world once inhabited by their parents and grandparents: one where everything felt safe and certain. Rather, everything in Erika and Oskar’s world is uncertain and incomprehensible. The young couple’s inability to find their place is manifested metaphorically in the fact that they don’t even have a sheltered place to meet each other: the two rendezvous in a city park, where they must huddle beneath a pine tree when it rains. Oskar and Erika are like excess individuals whose love lacks its own place in the world.

The novel’s modernist undercurrent is reinforced by its format: Tammsaare presents the events in diary form, which, according to his introduction, has merely been “edited for print”. (I might mention that the original manuscript, in Tammsaare’s own handwriting, has been preserved in archive.) This literary trick bred confusion when the novel was published, and continues to cast doubts today. There are still some who believe Tammsaare did not personally write the work, but did indeed find a manuscript penned by an unknown university student.

At the time it was published, I Loved a German stirred very conflicting views among its readers and critics, and does so to this very day. Doubtless, this is the firmest proof that the work has not lost its topicality. Rather, it has perhaps become even more meaningful over time, and not only for Estonians.

Even today, we continue to face the painful questions that Tammsaare raises in the novel. How can one orient him- or herself in our all-too-rapidly-changing world? How can one maintain his or her identity? How can love be preserved? Has anyone really found the answers yet?

[1] Corporations are European student organizations similar to US fraternities. Estonian corporations continue the Baltic-German tradition and closely resemble their historical German counterparts.

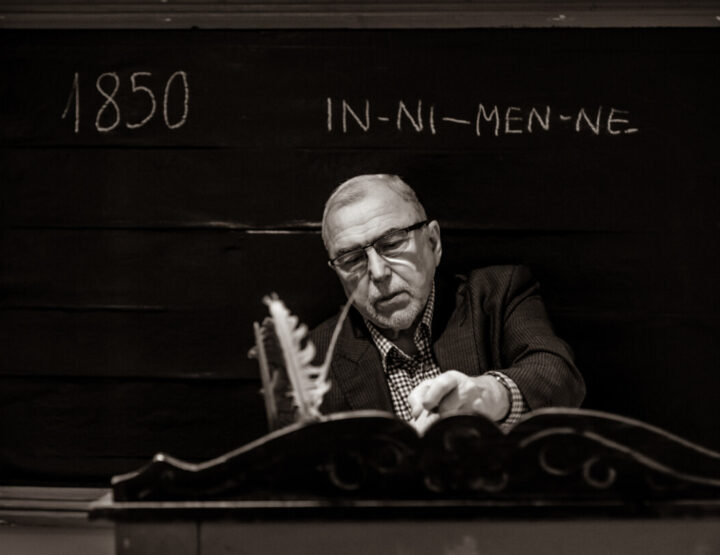

Maarja Vaino (1976) is a literary scholar and the director of the Tallinn Literary Centre. Her doctoral dissertation Poetics of irrationality, which scrutinizes the works of A. H. Tammsaare, is an outstanding study of the Estonian classic.