When Estonia gained independence in 1918, one of the first tasks of the new state was to tell the rest of the world that it exists. Diplomats went to the relevant European capitals to negotiate and lobby for the recognition of their country. Over a century later, Estonia may be called a well-known and established nation – and in 2020/2021 even a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council – but the fight for visibility remains a constant call. This is still one of the main tasks of the diplomatic staff of the country, but, additionally, of the arts and their export. The presentation of Estonian cultural manifestations abroad, can support diplomatic staff. Certainly, the most successful examples are the music of Arvo Pärt (*1935) and Veljo Tormis (1930-2017), but literature can also make a profound contribution.

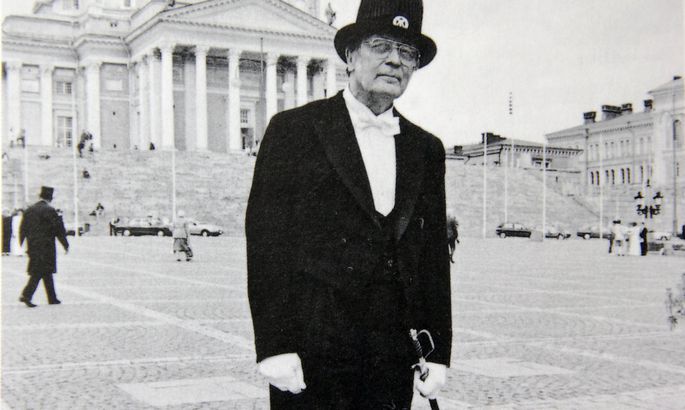

Here, Jaan Kross (1920–2007) fits as one of the best examples, as he is also one of the best witnesses of this republic. He was born 17 days after the signing of the Tartu Peace Treaty, which can be regarded as the definitive birth certificate of Estonia. Kross was a law student at Tartu University when Estonia was occupied by Soviet troops in 1940 and survived the subsequent Nazi occupation (1941–1944) in different positions, although he was imprisoned for some months at the end of that occupation. He escaped when the Nazis fled the advancing Soviet army, only to be imprisoned again in 1946, when Stalin’s grip on Estonia strengthened. The following eight years (which he spent in Soviet camps and in Siberian exile) were, of course, an irreplaceable loss of time, but at the same time an extraordinary study period: “Being able to investigate and interpret an incredible variety of people in situations that are completely atypical for them with all their changes and self-assertion under laboratory conditions” – as he ironically formulated it in a small autobiographical sketch in 1982. He returned to Estonia in 1954 and lived the following half century as a freelance writer in his native city of Tallinn. When he died in 2007, he left us 11 novels, 6 novellas, 26 short stories, 6 collections of verse, 6 collections of essays, 2 volumes of memoires, 2 plays and numerous translations and other texts.

Why choose Jaan Kross?

There are hundreds of other writers in Estonia, some of them having even published more books, but Jaan Kross certainly is the best known and the most translated Estonian author ever. What makes the oeuvre of this writer so exceptional? Why do we continuously reread his works? Why do new translations continue to appear?

There are surely as many answers as readers of Kross, because everyone has their own favourite. Yet, one thing should be beyond doubt: it is the specific mixture of the national (far from being nationalistic!) and the universal, which makes Kross interesting for readers abroad. For Jaan Kross, Estonia and the Estonians are the starting point for everything he writes. However, if you think that means – therefore – the work of Jaan Kross can only be understood with the necessary knowledge of the Estonian background, you are wrong. It is the other way round: the necessary knowledge about Estonia can be obtained by reading the work of Jaan Kross.

Reading Jaan Kross means, in addition to dealing with the general ethics questions of mankind, learning something new – and I guess that is what most readers want. It is not simply the style and intrigue we love when we read Gabriel García Márquez – we also want to learn something about South American societies. It’s not only the moral issues that fascinate us with Nadine Gordimer’s works, we also want to learn something about South African apartheid. With Toni Morrison, it is not only her fascinating characters that captivate us, but also her treatment of slavery and American history. We enjoy Orhan Pamuk not just due to the suspense of his books, but also because we read something about present-day Turkey. Herta Müller convinces us not only through her treatment of language but also because we get insights into the totalitarian system in Romania – just to mention some examples and to confine myself to winners of the Nobel Prize. Jaan Kross does not belong to this last category, but many critics, colleagues and readers ranked him high for this award in the 1990s and the beginning of the 21st century.

For a great deal of his historical fiction, the prose of Jaan Kross covers the period of the early 16th century up to his own lifetime, the end of the 20th century. With the last period he left the realm of historical prose but the transition is slight and almost en passant – as is the transition between fact and fiction, which can best be exemplified with the famous subtitle of his novel Mesmer’s Circle, which runs: “Romanticized memoirs just like all memoirs and nearly every novel”.

Starting in the 16th century

The earliest novella by Jaan Kross is set in 1506; The Four Monologues on the Subject of Saint George (1970) are small snapshots from the turn of the Middle Ages to modern times, in which the whole world of Kross’s later oeuvre can be found. The scenery is Tallinn, and later, almost everything written by Kross takes place in Estonia. The milieu is the grey area between Germans and Estonians, which is another important feature of Krossian prose. A frequently returning subject is the conflict between adaptation and resistance, between uncompromising self-assertion and self-confident compromise. The main character in the Four Monologues is Michael Sittow, a historical person who was born in Tallinn – probably in 1469 – and died there in 1525. In the meantime, however, he was in Europe, a student of Memling and later a painter at the Spanish court and in the Netherlands. Back in Tallinn for inheritance matters, he falls in love and decides to stay. At that time, he was already an established painter, but the local artists wanted to get rid of the unpleasant competitor. By rigidly adhering to their guild rules they demand a piece of practical work as proof of his skills. However, the famous painter complies with the requirements, disregards the humiliation and delivers a masterpiece so that he can stay in his homeland. In this concise narrative one can see that the prose of Jaan Kross is not about exotic small peoples in north-eastern Europa, but about general human problems and European cultural history.

This continues in the tetralogy Between Three Plagues (1970–1980) which one might call the magnum opus of the author – and not only because of its far over 1,000 pages. It is built up as a biographical novel of – probably Estonian born – Balthasar Russow (c. 1536-1600), a pastor at the Estonian Holy Spirit parish in Tallinn and author of the famous Chronicle of Livonia (1578, 1584). The first novel starts in the 1540s and ends in 1600, when the political conditions have fundamentally changed and medieval Livonia has vanished from the map. During the Livonian War, Northern Estonia becomes part of Sweden, the South comes under Polish rule, the islands are occupied by Denmark and Russia under Ivan the Terrible, who was a regular, but very feared visitor. The war is accompanied by various plague epidemics, occupations and peasant rebellions and among all that the pastor tries to write his chronicle, because he wants ‘to tell the truth’. But what is the truth? Who (dis)likes it? How can the writer manage to survive? It immediately becomes clear that this problem is not restricted to the 16th century or to Estonia. What are the three plagues? The horrible conditions of those days? Perhaps the three European powers, Sweden, Poland and Russia, who are fighting for supremacy in the Baltic Sea region? Or war, hunger and disease? As Kross wrote this in the 20th century, maybe the plagues are Nazi-Germany, Stalin’s Soviet Union and the Western Allies who abandoned Estonia (together with Latvia and Lithuania) after World War II. Maybe the word “between” is the most important of the three words of the title. Estonia and Estonians are always between someone and something.

The readers will decide, and they have plenty of time to think about it while they work through (and enjoy!) the extremely rich and baroque language of the author. Kross, who started as a poet, said in another context: “Rhymed verse is a voyage on a river, free verse on the sea”. In this novel, one is inclined to say, a sea vessel escapes the waves and heads for heaven. Jaan Undusk characterized Kross’ style in a homage from 2000, as follows: You almost never simply write: “He sat down on the bed.” You don’t even write: “He sat down on the hide duvet cover of his marriage bed.” For the most part, you write something along the lines of: “With a light squeak of the box spring, he sat down on the dog hide duvet cover of his marriage bed, already somewhat moth-eaten in its crevices.”

The following centuries

In his following novels, Kross continued to cover the Estonian centuries with various individuals, different approaches, and multiple plots. The Novel of Rakvere (1982) is situated in the 1760s and describes the struggle of the town’s inhabitants for their own rights, which date back to the 13th century. Jaan Kross’ best known novel, The Czar’s Madman (1978), is situated in the 18th century. Here, for the first and only time the main character is not Estonian, but the Baltic German nobleman Timotheus von Bock (1787-1836). He was a confidant of Russian Czar Alexander I and had promised to always tell him the truth. Yet, eventually, the Czar could not bear the truth anymore and von Bock was detained, isolated and tortured. For years he disappeared from the scene before he was officially declared crazy and could spend his last years relatively free on his Estonian estate. Finally, however, von Bock decides to escape with his wife and child to Western Europe. However, when they go to enter the hired ship in Pärnu, von Bock withdraws: “I cannot go … Only those who want to take revenge go abroad … If you want something more important, stay at home … – this is my battle – with the Czar, with the Czarist Empire, with what we have – … No, no, if you leave already, then not to Switzerland. Then to,” he pointed into the darkness behind the windows, “to Irkutsk and further, where the others already are, for me the only possibility to be is where I am forced to be! To be there – like an iron nail in the flesh of the Czarist Empire…” (p. 268-269) This is a confession: flight would have been surrender and subordination. To stay home is an uncompromising protest, a disturbing and stubborn presence that is so unwelcome to the rulers.

The next large novel, Professor Martens’ Departure (1984), takes place at the turn of the 19th century to the 20th century and displays an Estonian born jurist who made a diplomatic career in the Russian government – this was the only possibility as there was no such thing as “Estonian diplomacy”. Nevertheless, the protagonist tries to enlighten a journalist who asked him during the peace negotiations between Russia and Japan in 1905 in Portsmouth: “But you as Russian by origin – Oh, you’re not Russian? Well, you as a German, isn’t it – oh, you’re not German? Who are you then? Pardon me? Eskimo? No? Estonian? What kind of people is that?” This subtle passage says everything of being Estonian and finding a position in the world.

The author’s own history

The beginning of the 20th century has been topicalized in the novel Elusiveness (1993), displaying two Estonians at the beginning of a (great?) career, which abruptly is ended by German executioners. Jüri Vilms (1889–1918), one of the founding fathers of Estonia, was murdered by German troops in Helsinki, his biographer Aleksander Looring (1910-1942) faced the same fate in Nazi occupied Estonia. In the 1920s and 1930s, Estonian born Bernhard Schmidt is also featured in the novel Sailing Against the Wind (1987). The 1930s are covered by the beginning of Treading Air (1998), a novel about Estonia’s struggle to survive in the 20th century, and by The Wikman boys (1988), a picture of the first generation of republic born Estonians finishing school in the years 1937 and 1938. This generation faced the surrender of ‘their’ republic in the novel Mesmer’s Circle (1995), which centers on the where the tumultuous years of 1940 and 1941.

Numerous short stories provide details about the post-war times and the years spent in imprisonment and banishment, followed by an entire novel about the first year back home in Estonia: Excavations (1990) is a picture of Estonia in 1954, one year after the death of Stalin. Finally, there is Tahtamaa (2001), the novel over recently freed Estonia in 1993/1994, when exile Estonians show up in Estonia and try to make a fortune.

In all his works, Kross plays with the possibilities of history, making a tightrope walk between historical truth and historical probability. If a thing is proven to be a historical fact, Kross would never dare to ignore it. Yet, as soon as something cannot be fully proven, the author’s imagination rushes on. Thus, literature can provide explanations for things we don’t know for sure. Perhaps even as an explanation for why Estonia exists at all. Reading Jaan Kross, we understand the phenomenon, as most of his Estonian heroes know how to stay alive and avoid direct confrontation. Like Estonia. In this respect, Jaan Kross is a real ambassador of his country, as his novels bring Estonia to the rest of the world. The message is universal, but the packaging is Estonian.

Cornelius Hasselblatt held the Chair of Finno-Ugric languages and cultures at the University of Groningen from 1998 to 2014. He wrote numerous articles and books on Estonian literature and translated the works of more than thirty authors from Estonian into German.