Siuru, a literary group of the utmost importance in Estonia’s cultural context, was founded in May 1917. It was the second-to-last year of World War I, bringing pivotal events that included the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and Estonia achieving extensive autonomy from the Russian Empire: a hint of freedom was in the air. Political exiles of the 1905 Russian Revolution were allowed to return home. The original members of Siuru were Friedebert Tuglas, Henrik Visnapuu, August Gailit, Marie Under, and Artur Adson. Johannes Semper joined later that summer. Tuglas was already a well-known author, while the others had yet to make names for themselves in Estonian literature.

What kind of a group was Siuru, which emerged in the spirit of European modernity? It was bold, free, spirited, erotic, and poetic: “writing that extended from the unusually sensual to the roughly scandalous”. Most importantly, the group constituted a core that drew into its orbit a community of writers, artists, and actors, and also laid the foundations for a publishing firm that released Siuru’s own poetry collections and close to twenty-five other books. They called themselves the Six (White) Chrysanthemums.

Siuru’s only female member, Marie Under (1883–1980), was made the group’s chairman (the irony of this gender-specific title was not unintentional). The writers had nicknames for one another, and Under was their “Princess”. Her debut poetry collection was published in the first year of Siuru’s existence, and its passionate and shocking romantic sonnets became so popular that a second printing was needed by the end of 1917.

Artur Adson (1889–1977), who was Under’s smitten admirer and future husband, performed the duties of Siuru manager and “the Princess’s Page”. His poetic self emerged amid the group’s literary fervor, writing in his own native South Estonian dialect.

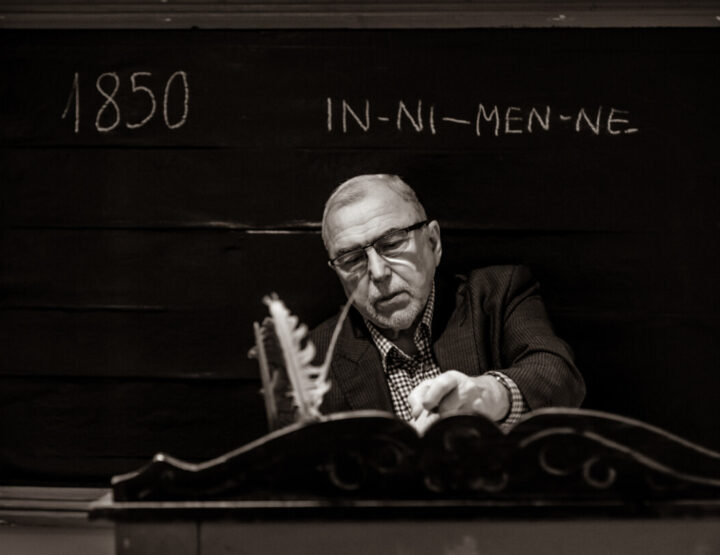

Where there is a Princess, there must also be a Prince: this nickname belonged to Friedebert Tuglas (1886–1971), who had returned to Estonia after 11 years of exile in Europe, and was also called “Felix” after his novel Felix Ormusson. Tuglas is considered the “grand old man” of Estonian short-story writing, but when he was still at the height of his youth, he penned the celebrated kaleidoscopic novella Maailma lõpus (At the End of the World, 1915), which tells of a young man who falls in love with a giant-woman.

Henrik Visnapuu (1899–1951; a.k.a. “Prince Visna”) and August Gailit (1891–1960; a.k.a. “Ge”) were a vital creative duo who tirelessly invented new bohemian tricks. Visnapuu described his friend Gailit as being a remarkably tall man who would laugh with overbearing mirth in cafés and had only then – as Siuru formed – vowed to someday become a writer: his debut in 1910 hadn’t been a memorable one. Hidden beneath Gailit’s laughter and jocosity, broad intellect and gentlemanly demeanor was a gentle soul. Born in metropolitan Riga, he was a true dandy. All of Siuru’s other members, with the exception of Under, hailed from south Estonia, but Gailit himself was an impressive mixture of Estonian, Latvian, and Livonian heritage. He lived in Riga from 1911–1916, worked as a journalist, and was a correspondent for Latvian, Estonian, and Russian newspapers during World War I. Gailit would read aloud the stories assembled in his collection Saatana karussell (Satan’s Carousel, 1917) to his fellow Siuru members, filling them with the conviction that the author of those fantastic tales would one day be a literary great.

Henrik Visnapuu’s collection Amores was also published by Siuru in 1917. The fiery love poems left Tuglas with no doubt when he wrote his review: “He is a born poet; his path is preordained, be that good or bad…” Even today, Visnapuu’s later romantic poetry is unsurpassed. He recalls the strong influences of three women in his memoirs: Marie Under, Isadora Duncan, and Ella Ilbak. The latter, Estonia’s first professional female dancer, likewise attended Siuru gatherings.

Johannes Semper (1892–1970) joined Siuru shortly later and was nicknamed “Asm” – a reference to the German author Otto Ernst’s novel Asmus Sempers Jugendland (which appeared in Estonian translation in 1912). Semper’s first poetry collection, Pierrot, was published in 1917, and stylistically complemented the poetic renewal that was underway.

Each member of Siuru somehow altered the language and nature of Estonian literature. The spirit of their endeavors is indirectly referenced in the group’s name: “Siuru” was a mythical fire-bird in the Estonian national epic Kalevipoeg. Yet with their puckish attitudes, they also altered the image of the writer into a collaborative member of a social circle that holidays together, performs together, and co-organizes bohemian events for the release of their works. They even devised a highly unconventional plan to occupy a tower along Tallinn’s medieval wall: both for its romanticism and to house club activities. Nevertheless, the grand idea remained a mere castle in the sky, as they lacked the financial resources for renovations.

In September 1917, a truly bohemian affair was held at the Estonia Theater in Tallinn: a literary evening complete with lotteries to support the publishing of Siuru members’ works. The profits were used to establish Siuru’s base capital. Artur Adson wrote that Gailit and Visnapuu planned to “usher in the evening with a true carnival by speeding through the city streets in trucks, dressed as Pierrots, Harlequins, and other costumed heroes, throwing flowers, playing music, and other gaieties.” Although that part of the evening was canceled, the frolicsomeness was still pulled off through lottery prizes, which included a rendezvous with an actress, a kiss from a poetess, and fifteen minutes of a writer at the winner’s service.

Siuru often met in cafés. Visnapuu recalled that there was a table for twelve permanently reserved for Siuru members and friends at the Tallinn café “Linden”, with a flag bearing the group’s angel logo in the center. One part of café life was composing frivolous postcards for members and friends who were traveling, with everyone present adding short, witty contributions. The café atmosphere was well-suited to both creative work and merrymaking. Once, an intense bohemian pub fight even broke out in a Tartu establishment: when a coupletist decided to poke fun at Siuru onstage, baked rutabagas and raw eggs (which some had had the foresight to bring) began to fly. Unfortunately, other patrons also joined in the brouhaha and a fistfight broke out between the bohemians and the bourgeoisie. This made the establishment very popular for a while among customers hoping to witness a similar conflict.

Siuru members vacationed together, and often performed together as well. A romance between Marie Under and Friedebert Tuglas unfolded in Siuru’s first year, making both writers’ works shine with particular brilliance during the period, and leaving behind some of Estonian literary history’s most beautiful love letters: “How could I sleep when I love you so?”

Siuru’s twilight fell at the beginning of the Estonian War of Independence, in the fall of 1918. Visnapuu and Gailit went to the front lines, where they were war correspondents.

In Siuru’s later works, the group’s utopian spirit of liberty is perhaps best embodied by the eponymous main character of Gailit’s magnificent novel Toomas Nipernaat (1928). Nipernaat is a man who leaves home every spring to roam the land freely all summer. His warm months are filled with adventures, fairy tales, and love stories. Although he may appear careless, fleeing when someone’s heart has been broken, the eternal wanderer leaves a gentle and lasting impression on his own soul, and of those he leaves behind. Gailit was the most widely translated and internationally renowned Estonian writer in the years 1930–1940. Toomas Nipernaat has been translated into nine languages, and will hit an even ten when it is published in English next year.

Elle-Mari Talivee (1974) researches Estonian literature at the Under and Tuglas Literature Center’s museum department, and at the Estonian Literature Center. She is very fond of cities with rich literary histories and gardens.