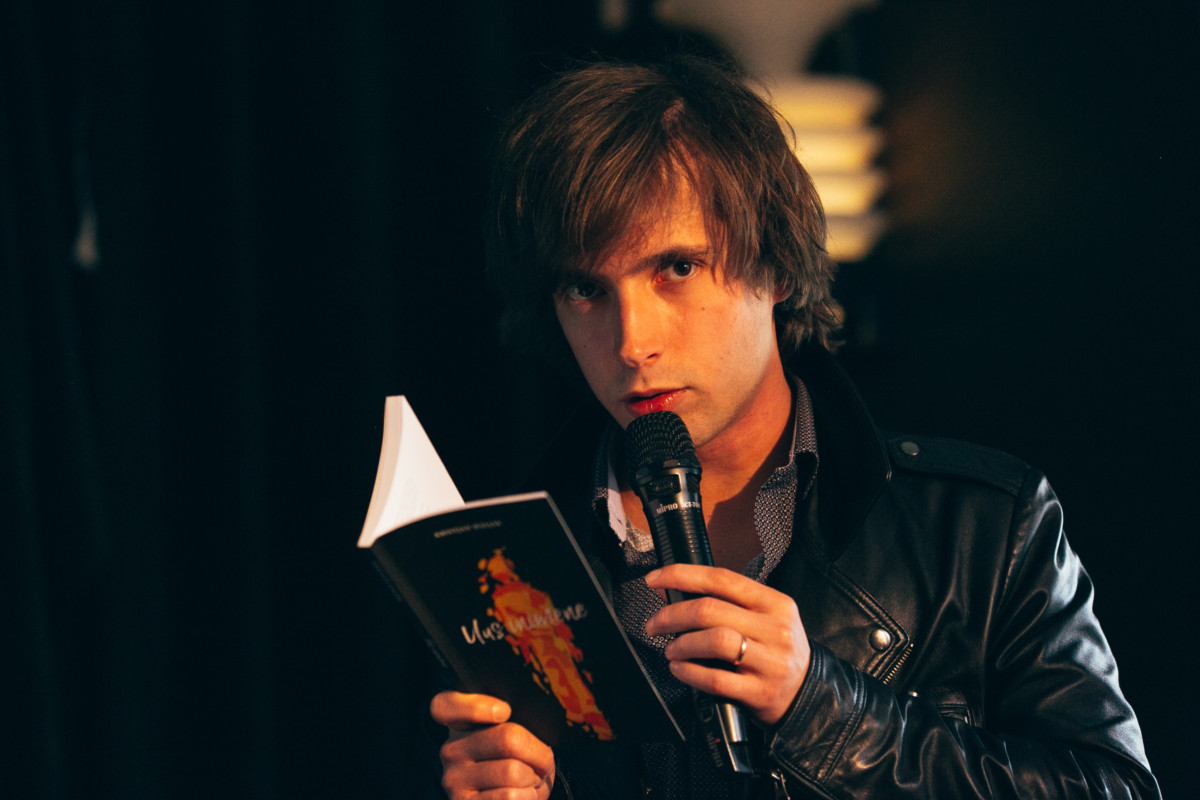

Kristjan Haljak is a poet, translator, and instructor of literature. Haljak has occasionally been called a Decadent (no matter whether seriously or in jest), and other times a continuer of the surrealistic tradition. Yet, regardless of how active these discourses are or the number of rebirths they undergo, none of them are adequate to pull apart the meanings embedded in his writing, which is already coated in a fine residue of concepts. Currently, Haljak has written four poetry collections (Fever, 2014; Conceptio Immaculata, 2017; A New Man, 2017; and Verlaine’s Revolver, 2018) and has translated two works of Baudelaire into Estonian (My Heart Laid Bare and Artificial Paradises).

It’s unusual for a person to read, and even less unusual for them to start writing. To quote the heterodox thinker Barry Sanders: “[We live in] a world peopled with young folk who have bypassed reading and writing, and, and who thus have been forced to fabricate a life without the benefit of that innermost, intimate guide, the self. [—] It is a world in which young people seek revenge and retaliation rather than self-reflection.” How did you arrive at reading and writing, and how was it that they no longer let you go?

I’m not about to start waving my finger around, saying that not reading produces dim-witted idiots, suffering, death, and violence. It’s highly possible that reading and writing are useful means for structuring yourself and your surroundings, for “intellectual cosmetics”, but I don’t believe the world’s pain, death, and anguish are anything that can be avoided by it or that it can manage to ward them off. To paraphrase Michel Houellebecq, perhaps you really can say: If you’re unable to place your sufferings into a definite structure, you’re screwed. And since we’re already namedropping, William S. Burroughs said, in maybe the 60s, that given the immediacy and possibilities of film as a media, it’ll be a wonder if anyone continues to read and write books.

I suppose I read books when I was a kid. Back then, it was (still?) the norm. My deeper interest in literature developed later in primary school. I don’t know why it hasn’t let me go. There’s no scene more atrocious than a young man in his prime who wakes up on a sunny summer morning and grabs… a book. I’ve simply been involved in literature the longest; otherwise, I could just as well dedicate myself to some other intellectual sphere. And you do have to dedicate yourself to something… Where else will you find satisfaction? Self-destruction, licentiousness, and other forms of entertainment are all nice and trying ways to pass away your days, but all in all, you’re hardly likely to trump intellectual activity. Suffering should be placed in a structure. […] Otherwise you’re screwed…

Building up your academic career, you’ve compared André Breton to the Estonian poet Andres Ehin, and I hear you’re working on Lautréamont and the Estonian modernist Jaan Oks in the framework of your doctoral studies. What does modernism more broadly, as well as its individual expressions such as surrealism, mean to you?

As for surrealism, it is, on the one hand, a trend of literature and art that does belong to a very specific period. By imitating its specific characteristics, it’s possible to sempiternally produce and reproduce endless writings and visual artefacts that can be classified as surrealistic, but which possess an imitative, copy-like nature that today make them almost outdated and unfashionable. On the other hand, one must consider the fact that surrealism is (or at least was, as the original surrealists believed) something significantly greater than a collection of techniques and motifs. Surrealism was and continues to be all-encompassing, transcending art; life-encompassing, transcending life. It turns boring only when artists attempt to “do surrealism”. When nothing takes form aside of a prankish façade; when the only sense it gives is the ambition of imitation. Surrealist art and the surrealist perception existed before and have existed since the birth of the respective movement. The Arab poet Adunis has compared surrealism and Sufism and found their main shared component to be an endeavor towards a certain absolute. Ultimately, all surrealist literature is that which strives to leave the ordinary and banal; which expresses belief in what lies behind, above, below, and next to the shadow of the superficial; which knows that things do not appear the way they should always appear. And it is that which knows and recognizes an obligation to demonstrate that man has been given language for it to be used surrealistically.

The French language and people: what is it about them that fascinates you? Is linguistic proficiency important? In his memoir, the British writer W. S. Maugham said, “It seems hardly worthwhile to take much trouble to acquire a knowledge that can never be more than superficial. I think then it is merely a waste of time to learn more than a smattering of foreign tongues. The only exception I would make to this is French. For French is the common language of educated men, and it is certainly convenient to speak it well enough to be able to treat of any subject of discourse that may arise.” For that matter: do you feel a need to go beyond Estonian-language borders with your writing?

I don’t know whether it was predetermination or chance that led me to French culture. That’s what happened and there’s nothing I can do about it. Had I been influenced by some other chain of events, then might I have immersed in Polish or Spanish culture instead? Since I’ve been taught to be critical of any kind of substantiality (and, in a sense, cultural relativism as well), I won’t go so far as to claim that there exists a coherent, unified, ideal Frenchism that includes values, powers, and possibilities with a radically limited right to exist outside of it. However, linguistic proficiency is definitely important and, (though perhaps it really isn’t defining: there are many good, fascinating authors who don’t speak any languages aside of their mother tongue) no matter what your attitude might be towards linguistic-cultural relativism, your opportunities are certainly broadened by speaking different languages. Going further than Estonian-language borders in my writing is intriguing as an idea, but I don’t know if I’ve personally made all that much of an effort in doing so.

What is your creative process like? Do your poems require a lot of time to settle or for tweaking? They sound spontaneous, jazz-like, but at the same time, I’ve realized that is the greatest ability you can have: to make an immense effort in creating something that is seemingly as light as a feather.

It all depends on what kind of a poem or a cycle I’m writing currently. Quite often, I use techniques similar to cut-up. Lately (basically in all the poems written after those I published in Conceptio Immaculata and A New Man), I’ve been thinking on a level of composition broader than that of individual poems. The collections I just mentioned were mostly compiled from freestanding poems, even though a certain cycle-like quality surfaces there, too. I always tweak both free-standing poems and larger compositions: my initial spontaneous bursts need polishing. If I do manage to achieve the allusion of spontaneity or lightness, then I can only be happy for it.

Repeating the widespread truth that content and form are inseparably connected seems downright cliché… So, I also attempt to break ingrained formulaic patterns; to write differently; to not repeat myself.

In Verlaine’s Revolver and other newer projects, I keep up the fight (and, considering the modernist tradition, it’s somewhat of an ancient fight already) to break down barriers between poetry and prose, originality and plagiarism. I experiment with (Soviet) encyclopedias, Estonian and world poetry classics, and 20th-century prose that shaped the Estonian national narrative one way or another. When doing so, I process my sources for material such that the “modernity”, which at least still blinds me momentarily, might flash for even a split second over all that stylistic-thematic and methodical old-fashioned-ness.

Your latest poetry collection, Verlaine’s Revolver, was published in late 2018. Could you say a couple words about it?

Obviously, the title references the weapon one poète maudit, Paul Verlaine, used to attempt to kill another, Arthur Rimbaud. Even though he originally bought the gun to kill himself. My experimentation with late-romantic and Decadent tradition branches off from there. The book itself is composed of seven parts, each with nine poems, and each poem comprising fourteen lines. The book’s original working title was The Sonnets, which is an unambiguous reference to a second-generation author of the New York School – Ted Berrigan – whose “sonnetoids” were largely composed of quotes from literary classics, the works of Berrigan’s confrères, and… Berrigan himself. Suffice it to say that the original methodical principle of Verlaine’s Revolver was similar, likewise.

“outside / the window jazz streamed from speakers / soft soft sound and sobs and / bass and a vodka bottle to boot …” In addition to a jazziness, your writing is pervaded by two other relatively musical topics that are distinct in Estonian culture, but seemingly reach a consensus through literature: religiousness/spirituality/whatever and eroticism/carnality/urge. This is also reflected in the title of your 2017 collection Conceptio Immaculata. What is your relationship to music, and are literature and music connected?

I listen to a lot of music, both while working and for pleasure, but unfortunately, I lack the ability to make it myself. There’s probably no point in digressing here into the historical connection between music and poetry, but I can say I always regard writing’s sound as crucial. I’ve also received feedback that readers have been helped with some poems by hearing me read them aloud in person. Since the lines in my poems are often fragmented and graphically unmarked on a visual scale, I understand that some rhythms may indeed be hard to pick up on paper. However, I hope this certain multiplicity of forms determined by the medium (or, to put it a little disparagingly: the confusion and complication of forms) isn’t overly repugnant to readers.

I suppose the other two topics intertwine, collide, and coexist in my life without annulling each other. It feels like I mostly exist within my own head or my apartment, picking away at writing, and mainly that of others. There are, of course, both positive and negative excesses and deviations and wanderings and love and what all else. How couldn’t there be? And from a surrealist perspective, the line between life and art, between life and poetry is very obscure.

What kind of contemporary literature intrigues you? How much do you read? Do bookshelves play a big part in your home?

I read a lot, though certainly not only prose. As for poetry and prose, I can’t say I have an especially obscure taste when it comes to contemporary authors. I reckon the writers I read are quite well known. I’d be exaggerating if I said I’m very up-to-date with what’s going on in the Western European poetry scene right now, for instance. And it is, unfortunately, hard to keep up. It’s even difficult to read all the poetry published in Estonia. But you’ve got to keep your eyes open – no one else can be blamed for your own laziness. I’ll be horribly hackneyed once again here, but I like, for instance, Michel Houellebecq’s prose (and his poetry is fantastic, too, of course). As for American authors, I’ve recently been reading a lot of Frederick Seidel’s poetry. There’s something about the Anglo-American post-beat tradition that hasn’t been reflected very much in Estonian poetry, but which has fascinated me since I was a teenager. Bookshelves play an important part at home, but there’s unfortunately not enough room for them and I don’t know or can’t be bothered to figure out how to solve the problem. There are better problems to deal with.

You’re an instructor. Has it been a logical course for your life to take? I know a few young teachers who have ended up feeling distressed once they chose the teaching path and seeing how curricula that could span entire years are forced into the smallest-imaginable time-spans; how special-needs students aren’t given enough individual attention, but instead are all squeezed into one class; etc., etc. What’s your opinion of the teaching profession?

I studied French language and culture at university. Becoming a teacher is seemingly logical, in that sense. Still, I have to admit that I did simply wind up as one… Strangely, I enjoyed the job, and I like it to this day. It offers a certain social satisfaction that I don’t get from puttering around at home alone. I haven’t encountered the distress you mentioned in full: I work part-time, I’m not a head teacher, etc. Even so, I can fully understand someone feeling like that.

To conclude, what are your future plans?

I have a couple of unfinished manuscripts I’d like to complete. I’m also working on a few translation projects – I suppose the most interesting ones are André Breton’s Surrealist manifestos and Lautréamont’s The Songs of Maldoror. But I’ve got other projects as well. If possible, I’d like to wrap up my bigger translation projects soon and focus on writing my doctoral thesis.

Siim Lill is an award-winning artist, writer, philosopher, historian, and biologist.