Thirty years have passed since the release of Border State, a novel by Tõnu Õnnepalu (b. 1962) that was published under the pseudonym Emil Tode and has become one of the most-translated works of Estonian literature. To mark the occasion, we spoke to the author about the unattainable past, borders that can and cannot be crossed, East and West, and the strands connecting nature and culture.

Border State was published 30 years ago. Although you wrote three poetry collections before it, the novel is what brought you fame (I counted 19 languages into which it’s been fully translated to date[1]). What did the success bring?

For some reason, people believe that success is something to be desired and envied. Sure, it brings experiences that otherwise may never have been had (and here I mean painful, traumatic, but perhaps also thereby deep encounters), and given that experiences are a writer’s sole capital, it naturally has value as well. There are the superficial and material aspects as well. Those translations allowed me to survive the poorest and most meager years of Estonia’s economic transition in the 1990s with relative ease—a time when the country had zero money for literature. I was able to keep writing.

In a sense, it was that part of the book’s success—all the trips abroad as a writer, as an author—that pushed me onto the path. Who knows, maybe I’d have gone into an entirely different field otherwise. But I can’t even say that for certain. Anyone who’s had one sip of the drug, who’s experienced the unique state into which writing elevates you—being far outside of yourself while simultaneously very close to yourself—can they ever settle for an “ordinary life” again? I’m afraid the temptation to try it again is too great.

Is that fortune? Fortune feels like a rather meaningless category when talking about creative activity… But maybe that’s precisely why it is important! In any case, it took years and years for me to understand that writing can be my fortune, my special little way of existing in this world. Success was suffering, compulsion, and obligation above all. Actually, I had no idea how to move on from that for a while. That’s all in the distant past now, luckily. I often think back on it as if it were another life lived by someone else—someone who, in a strange way, I myself was.

In a recent interview, you implied that the reason for Border State’s wider dissemination might be a certain 90s exoticism of the East. But that can’t be the only reason, as translations were also published later.

I think there’s no point analyzing how that book, and others of mine, have done; in scrutinizing their path to readers. A book is merely a reflection of a person’s life and there’s always something inexplicable in its “fate”. Some do well, even though they’re a shapeless form from which no one expects anything. Others have every imaginable advantage and fail at everything in life. Why? How? There are so many components to the solution, one of which is time and its zeitgeist. Though trying to somehow capture the zeitgeist is futile, of course. However, one tries to define a phenomenon, it is already the zeitgeist of the past. We grope our way blindly into the future, ignorant. It may be possible to capture something that touches others as we attempt to record it in writing; something that reveals to them their own experience that hasn’t a name, that cannot really be spoken yet.

Writing has been an extremely personal process for me from the very beginning; an attempt to speak about that which cannot really be spoken about, though it’s the only thing you want to discuss. I’ve managed to pull it off on occasion, more or less, and those have been the high points of my life, though the unutterable has mostly remained unutterable and so I don’t regard my career as all too successful. Let’s say it’s a 98% failure rate. But I’m not saying that two percent is insignificant. It’s a rather respectable effectivity. All in all, I’m content with my failure.

As Border State was the first book you published under a pseudonym (which I’m assuming wasn’t, in practice, with the intent to hide your identity?), one could, at face value, possibly conclude that you anticipated a different type of reception or impact.

It was meant to hide my identity. And it worked, at first. I didn’t want people to know who was behind the book when it was released. As I’d already written and published a few things, I wanted to avoid the connection. I wasn’t thinking about those things so clearly back then, of course; the pseudonym and everything was more of an instinctual decision. There were also practical personal considerations, of course—fear over what the reception of that type of book would be. And I suppose it was rather borderline (as with all my books), splitting the audience in two as if foretelling the overall division that we’ve come to today.

For me, personally, writing Border State in Paris was a kind of rebirth; my birth as a writer, though that sounds too ceremonious. But it was an existential change, I’d even say a physiological sensation, a bodily experience. Writing is a bodily activity, and it changes the body. I can’t really explain how. And it could well have been fantasy, but that’s what I felt then and still feel now. I suppose I wanted to give that new body a new name. Later, I realized that names are somewhat trivial, and no name can be given to such an experience of bodily rejuvenation, anyway. The author’s name is the most fictional element of any book. It’s total fabrication! That person doesn’t exist.

Border State has been labelled, among other things, “Estonia’s first gay novel”. At the same time, others have argued that the protagonist is androgynous, genderless.[2] What feelings does that engender in the author—the fact that, to this day, 30 years later, there are still articles, dissertations, and conference lectures that aim to crack some kind of a secret, some truth?

That’s no longer my present. A book becomes present again in the reader. That is where the book I once wrote lives its new lives, over which I myself have no power and about which I never really get to know anything. Some occasional feedback or commentary may be interesting, because it reveals something about the person who read the book. That’s when I get to experience the “ah-ha!” moment, to be amazed that it can be interpreted that way, too.

Writing a book is a lonely act, but publishing it is an extremely social act that, in retrospect, makes the writing partly social as well. Writing isspeaking with the Unknown. On the one hand, it gives you courage (the Unknown can’t argue back), but on the other, it requires courage (the Unknown can always turn your words against you, make them ridiculous, obliterate them). Writing is a leap into the unknown.

The 90s were a historical breaking point, I guess you could say, meaning a moment when there was a great amount of unknown, a lot of opportunities, and a moment of immense freedom. At such a point, it’s possible to say things that would be hard, if not impossible, at other times. That perhaps gives what is said a special value of truth. It’s just a hypothesis, of course. The 90s in Eastern Europe was a fresh, child-like time. There was a lot of idiocy and illusions, but also courage. Or was it really courage? When the old system ceased to exist, then a new one had to be invented whether you wanted to or not.

Just from the title itself, the conflict between East and West in Border State won’t let me go. The tension hasn’t dissolved even today. Is it at all possible to get away from that, and how?

The experience of conflict between East and West is precisely what I was trying to get off my chest! It was extremely personal, painful, and fascinating. The thing was simple: “we” here in the “East” stepped out of an old system and into a new one. We had to rethink everything, we encountered a different world and different people in the sense that they really did lead very different lives with different problems and amidst different convictions. In short, we inevitably had to change, relearn, and understand what was going on. But the West itself seemingly didn’t have to change, or rather people in the West didn’t realize that the changes affected them as well. People tend to continue living in the world they’re used to occupying, even when that world is disappearing around them.

The fact that East and West suddenly ceased to exist as competing systems changed the whole world order. It also changed the nature of the West, its ideas, its morals, everything. It changed the world’s system; a change that’s in no way ended (if it ever will). We’ve arrived at a new phase that’s nearly a mirror image of the first. Everything is backward, ominous, hopeless, chaotic. But I suppose that means it’s actually hopeful, too, and something new will emerge from the changes. Only it’s impossible to see what that is just yet.

Of course, I’m simply thirty years older now. When you’re thirty years old, the world that is coming (and it’s always coming—the world is an incessant comer) is very much your own. You yourself are still that coming… And then, one day, you realize that your paths have diverged. You’re still going your own way while the world is heading elsewhere. At the same time, I’m not sure that fundamental understanding ever changes over the course of our lifetime. We collect experiences that confirm it, phrases and notions that express it, but our attitude towards the world doesn’t change. Not our understanding nor lack of it. Perhaps the latter is even more defining. Literature comes more from a lack of understanding, being an attempt to understand. Loved ones are those with whom we share a common lack of understanding.

In your novel Salary: A Winter Diary (2021), you examined, among other things, Estonian literature and the status of Estonian writers, and it seems you hold a certain antipathy: “The Estonian writer is one type of the living dead. […] I would like to become a writer, not an Estonian writer.”

A writer is also a saboteur, a spy, a dubious character. I’ve always simply searched literature for that, which I need, and I’ve looked for it everywhere I can without differentiating whether it’s Estonian literature or any other. Naturally, that which is written right here and now in the same language that I speak is something special, something very intimate, by which I mean to say it might have what I’m looking for, but usually not!

For me, there are very high stakes at play in literature. Nationality, locality, temporality, they’re all just material and technique in writing. It actually speaks of something else. Something that matters more. And interestingly, I’ve noticed—take with the translations of my own books—that people tend to find something “else” that matters to them even where they shouldn’t be expected to find it. Their experience in life should be much different than my own, but that doesn’t count. Something else does.

I recently read Icelandic author Andri Snær Magnason’s On Time and Water (2019) and was fascinated by how we’re accustomed to speaking about nature with an economic vocabulary. In other words, nature has to be of some benefit (say, for tourism), as if it lacks its own value. You have a degree in biology and are simultaneously a writer. Do you think it might be the same with culture and literature?

Nature is of no benefit overall, of course. It simply exists and we don’t know why, because we ourselves are also a part of its existence, just like everything we make: books, cars, bombs, artificial intelligence—nothing exists outside of nature. We don’t fully know why we write literature, either. We simply do, perhaps because we’re used to doing it. But it’s certainly not wrong to speak about benefit—I read books only because they’re of some benefit to me. I use them to look for and find some kind of help, understanding, entertainment, whatever!

It’s the same with nature. Try as we may, it’s impossible for us to treat it entirely selflessly. Every tiny fish, every little plant, is trying to survive here just like every one of us. No matter what, the cost of that survival is a number of other lives. Environmental protection can be nothing other than humankind’s own protection. And that’s what it is: an attempt to preserve the world in the way that our species, and perhaps our civilization, can continue existing here in the precious way and with the values to which we’re accustomed (like love for one’s fellow man, helping others, human rights, etc.). We can’t simply protect abstract nature—we’re no gods.

All in all, we’re not so wise and powerful to truly steer the fate of this world and our own species. Time and again, we act indiscriminately, experimenting, probing, trying to understand and never achieving understanding. Literature’s role in this “ecosystem” might be the acknowledgement of our nonunderstanding; bringing us back down to earth when the waves of self-admiration and omnipotence (or triviality and unimportance) are crashing down upon us. Literature can remind us that we’re quite stupid, even though we’re amazingly smart. Quite evil, even though we’re sometimes amazingly good.

What can we expect from the near future in light of all this? What’s going to happen over the next 30 years?

Thirty years ago, when I was writing my first novel in Paris, there were about five and a half billion people on Earth. Today, there are over nine billion. Thirty years before that, when I was born, the world population was only three and a half billion. That’s the most radical change that has taken place during my lifetime. Compared to it, the collapse of the Eastern Bloc and such things are just a ripple. Border State is already a historical novel; it depicts a world that no longer exists. Stepping out onto the sidewalk in Paris in 1993, it was still possible to disappear, to become nobody, to become anybody. No one knew who you were because you didn’t have a phone in your pocket and everything that comes with it. It’s odd that just like everything else, technology is simultaneously liberating and enslaving. It’s simply no longer possible to experience that total freedom of being anyone, at least not naturally and without making much of an effort.

Books are companions in loneliness—it’s nice if they help us to get by better in any way. But I also don’t believe that one can understand humankind without understanding themselves.

Thirty years from now? Maybe AI will be writing novels about us, and we’ll read them (if we’re still reading) with gusto! The idea does make me feel a little queasy and I’d rather not live in such a world, but who knows. So long as there’s air, water, and food, meaning green plants that photosynthesize and nourish us, so long will we be able to live in this world. At every instant, the life that we live is totally self-evident and totally baffling, all at once.

Maia Tammjärv (b. 1986) is an Estonian literary critic and editor.

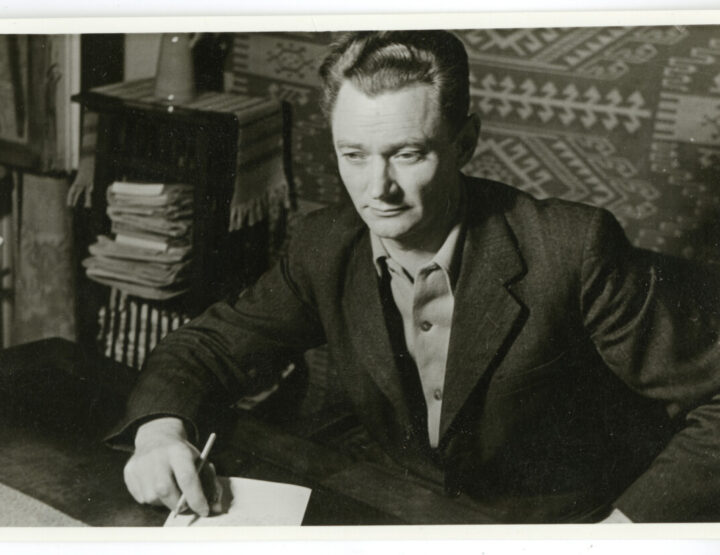

Photo by Triin Maasik

[1] https://sisu.ut.ee/ewod/oe/onnepalu/prose

[2] The Estonian language is non-gendered, allowing for ample ambiguity. – Translator