ELM: What to ask of a 32-year-old writer whose first book appeared 15 years ago, and who is equally busy as a TV host, restaurant critic, book reviewer, and market advisor to a cultural newspaper? Who has for years been an active journalist and worked in various advertising agencies? Who claims that he would actually prefer to sleep? To start with, let us ask: what are you doing at the moment?

KMS: I just took a goose out of the deep freeze to defrost so I can cook it tomorrow. I am also contemplating two pounds of beef fillets that must be coated with herbs and then stuck into the fridge to set before being cut up into carpaccio. Tomorrow, after all, is the anniversary of the Republic of Estonia and Shrove Tuesday as well, which means that I have to put the peas to soak and buy properly smoked ham and fat at the market. And naturally see that there is enough vodka, and put glasses into the deep freeze. So in fact I am quite busy at the moment.

ELM: We actually meant your creative work.

KMS: What can be more creative than creating a meal and consuming it in good company? I have said many times that writing poetry and cooking are activities for an impatient person. The result is achieved quickly, can be instantly enjoyed, and can even offer something to others. Besides, poets are rarely wealthy, and can afford little else but food and drink. Why not have the best of these then!

ELM: Very good food can cost a fortune.

KMS: Pah! Material costs a pittance. Work and skills are what push up the price. Once you’ve got the knack, you can work wonders. The same goes for literature.

ELM: Yes, let us talk a little about literature. You have been deeply involved in Estonian literature for at least 15 years, and you are not ancient. What has changed in literature during that time?

KMS: A big question. Everything and nothing. Writing and creating worlds is always the same constant progression, only things and people (and countries) involved keep changing. This of course has an impact on how everything is reflected in the textual environment. When we thought of ethnofuturism 15 years ago, we had no idea this was going to develop into something nationwide and ungraspable, which would burst out of control and develop a life of its own. Not that it ever could be controlled.

ELM: Ethnofuturism? It was allegedly you who invented the word. Could you elaborate a bit?

KMS: It would be a mistake to assume that ethnofuturism is a modernised version of some Finno-Ugric tribal movement. Although today, being twelve years old, it may well seem to be. Ethnofuturism as a progressive and invigorating way of thinking, which furthers diversity and sovereignty, suits all kinds of ethnos who have retained their ability to look into the future. All big nation-states are composed of a number of smaller ones. As time goes on, these smaller ones feel increasingly stronger. I’d say that ethnofuturism is a totally European movement, because Europe, which is doing away with its old frontiers, now offers new paths to dozens of nations who had little chance during the era of closed-in nation-states. That’s an understatement. Looking at the goings-on in Russia, it is also possible to claim that the fields of European and ethnofuturist thinking coincide. Perhaps for the first time in history they complement each other without conflict, steadfastly squeezing life out of big-state stagnation. For the past ten years, Russia’s European border has run not along the left edge of the Ural Mountains, but along fragments of nations with self-perception. Über-Russians have no choice but to surrender.

The ethnofuturist approach to existence recognises no borders or states. A dozen or so years after the birth of Christianity or Islam, these ideologies could have easily been regarded as ploys of a few Semitic tribes. The advantage of ethnofuturism is in having a more distant and profound background temporally, and living in that, rather than in either of the afore-mentioned religions. The fact that the idea progressed in Ugric nations is in a longer perspective just a circumstance, nothing else. What is significant about it is perhaps the fact that, relying on Ugric roots, it is hopefully possible to avoid getting trapped in ideologies and primitive monotheism. A Freemasonry hint – there is no Great Architect of the Universe, but an architectural firm. As good houses require. Not forgetting the trees. However, other people from other countries would probably say something entirely different. Who knows what’s right?

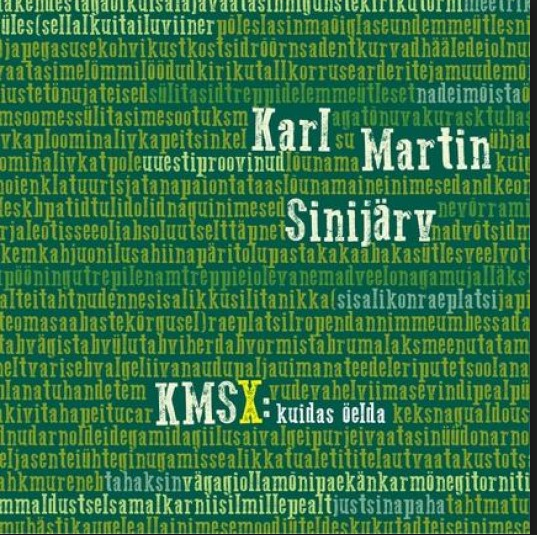

ELM: For your last poetry collection you got the best book of the year award. What next?

KMS: Next is to write the best book of myself. That would contain previous books, for example. In that case it should be the best, shouldn’t it? Or perhaps not. There is no hurry really.

ELM: You’ve been hosting a weekly TV cultural programme for three seasons. Is this something totally different from writing?

KMS: No it isn’t. I write all my texts myself. Besides, since I have no illusions about being an actor, and my memory is not what it used to be, I try to make the texts as short as possible and to the point, and let others do most of the talking. This must be the right thing to do because the programme is not about me, but about my guests. I am sure my experience in advertising helps a lot, probably also the poetry writing. The goal is to achieve precision in a few words without becoming banal or journalistic in a bad sense.

ELM: What about advertising and writers?

KMS: A number of good writers of the younger generation have, within the last five or six years, tried their hand at advertising; some are still at it. I had four years at the local branches of Saatchi & Saatchi and Ogilvy, first as a copywriter and then as creative director, and small apprentice jobs in London and Rome. Excellent experience, although too long in an office is definitely not good for one’s mental health. One year brought three awards, and the competitive impulse had exhausted itself. I still do this sort of thing as a freelancer – people know my line and then they give me a call.

ELM: Aren’t publishers calling, about a new book or something?

KMS: They did at some point, but I cannot produce books to order. I’m afraid to commit myself too much, or the whole thing might go wrong. It has happened. Let me produce something, and then we’ll see. Perhaps if I learned how to write prose it would be different, maybe a contract could be arranged on the basis of the idea and first chapters. But I’m not sure even then.

ELM: So when are you going to learn to write prose?

KMS: Well, I’ve done a book, a serialisation in a newspaper, together with a friend. I should turn it into a proper book. I am quietly busy with the next. As a rule, by the way, my favourite prose writers started at about forty, be they thriller writers or more serious ones. I think some experience is necessary before you start writing about it. It is good and proper to write poetry when you are young – it keeps the pen sharp and makes it possible to find the right form for the right things.

ELM: The Estonian population is hardly a million, so why the hell bother?

KMS: I think knowing Estonian, not to mention writing in Estonian, is an elitist pleasure in itself. It’s good to feel that you can do something best in the world. Someone might one day ski faster than an Estonian skier – although hopefully not in the foreseeable future – but others cannot produce better literature in Estonian. Sadly, a lot of world-class text remains unnoticed because it’s written in a remote language. But it exists, and that’s what really matters.

ELM: If you wanted to show off your language, what sentence or poem would you read out loud?

KMS: Öörõõmus õllesõõm, jäääär, töööööök. Just a few examples off-hand. I am sure there are more exciting things.

ELM: What is the country actually like where you live?

KMS: I advise everyone to come and see for himself. Low land and high ideas. If you happen to meet the right person.

ELM: There are still people who lament that everything was better before. The old time-machine game: what era and place do you think you would fit into best?

KMS: Can’t choose a time, but the place could be a bit warmer. However, if I had to choose a time, I’d like to live in an era when religions were not too important. I’d hate to see some faith-related gross stupidity emerging at the turn of the new millennium. All this violence, from time immemorial, shouldn’t happen. We have a nice saying, expressing disbelief, a wish to get rid of someone etc: go behind a tree! To go and stand behind a tree and ponder life is always worthwhile. Touch the tree.

ELM: Let us suppose that ultra-conservatives come to power and start cutting off support for culture, systematically, field by field. How would you line them up?

KMS: I would tackle this from the opposite direction. Meaning, who should get the money first? My priority is language and thought, which must be kept alive, nourished. Sport, physical culture, can come last. It truly doesn’t make sense when someone at the end of 30 km is crowned with a wreath and someone who arrives a few minutes later is down in the mud. In real life both are equally worthy. If possible, however, I’d support both, and everything in between as well, because in the body – and society is body – both the foot and the brain play a part. You can live on when the foot goes, but not if the brain dies.

ELM: Why do you think computers still can’t quite triumph over books?

KMS: They have totally different functions. Yesterday, for example, my computer crashed. No idea whether my texts of recent years are still there, but I know that those in the books are safe. There’s really no comparison. An airplane is faster than a car but we still need cars. And walking. There are no replacements: good things complement each other.

ELM: What would you show a writer who has never even heard of your country?

KMS: I would offer him a light meal and ask him to take the wheel. If he survives the local traffic, I would offer him a healthy drink and take him to the sea. And to a lake. And advise him to extend his hotel booking for at least a week. Estonia takes time.

© ELM no 18, spring 2004