Writer Indrek Koff takes a look at literature’s borderlands and asks what peculiarities might arise there.

For some reason, I’ve always felt that truly interesting things arise where borders meet. Where the cores of two or more areas blur and their differing parts blend to various degrees. Not such that either disappears, but that creates a third entity from the material that forms. Something that preserves, intact, the differentiating characteristics of each individual component.

I don’t mean to say, of course, that developed notions should be ground down and swept beneath a rug of oblivion. As for literature, the symphonic quality of the true novel is still thrilling, and true poetry still lifts us to greater heights with its beauty and elusiveness. And it will continue to do so.

With alloys, it appears, the likelihood of creating something new and intriguing is indeed a little greater simply because less effort is spent on the melting. The path hasn’t been fully smoothed just yet. True, one can’t say that originality or uniqueness in literature is what makes an experiment an experiment, as it’s impossible to create anything genuinely unprecedented in the field… That being said, literary experiments also aren’t overly common.

Another factor that ups the excitement of experimentality is the great danger of failure. An artist who attempts something “unlubricated” is exceptionally vulnerable, which is precisely what makes it so attractive. The courage to get down on all fours and crawl while testing. And this is, in my opinion, intriguing to both the “consumer” and the creator. If you aren’t prepared for a piece that you deem genius, or at least moderately adequate, to result in a certain degree of discomfort when it comes into contact with the audience, eliciting inexplicable reactions of disgust or, in the worst case, mere shrugs, then there’s no point in even undertaking the project!

Interestingly, the decision-makers who divvy out grant money have recently gained a greater appreciation for the blending of divergent branches of art. The word “interdisciplinary” slips its way into every official document imaginable, and anyone operating in the project-based cultural universe is essentially obliged to use it. I can’t deem this tendency overly meaningful, but there’s still something afoot. I suppose even officials think, dream, and hope. No doubt the collective intuition of bureaucrats in the cultural field has suggested that probing borders can sometimes be productive.

One apparent trend in original Estonian literature is the rising frequency of dramatization, and this is in impressively motley and entertaining modes of expression. Here, I don’t mean plays that are intended to be staged, but creative writing in a variety of other manifestations. It’s important to emphasize the word “frequency” because modern Estonian literature was essentially born on the stage – what literature-loving Estonian hasn’t heard of the Siuru literary group’s infamous ball? The scandalous fundraising performance made an immediate name for its members and collected the necessary capital for launching their literary project. Siuru texts are certainly enjoyable to read in and of themselves, but one can’t underestimate the draw of the stage.

Poetry theater, which lies somewhere in the gray area between drama and literature and is similarly underpinned by music, was practiced later in Estonia. Every budding poetry group has pulled off a more-or-less outrageous performance. Some have become legendary, others not, but each has occurred. In addition to intimate silence and the withdrawn reader, literature has sought live contact with a human of flesh and blood (such as Artur Alliksaar and his spontaneous performances in city buses during the Soviet occupation). One dazzling example of Estonian stage literature in recent years is Cabaret Interruptus, which was an event series that brought together younger poets and musicians in one-time performances that were something much more profound than ordinary readings. A wide range of hybrid literary performances can also be enjoyed on certain dates of the Estonian Writers’ Union’s long-running Literary Wednesdays series. The works of Ilmar Laaban, a classic of the surreal and undoubtedly the best-known Estonian experimental vocal artist, have been recorded and released. In more recent years, people have come to know and appreciate Estonia’s jack of all literary trades Jaan Malin, whose peculiar roars, whines, and growls bring an involuntary grin to one’s face while still penetrating the deepest levels of consciousness (or subconsciousness?). Malin often takes the stage with Roomet Jakap, a philosopher, conversing in made-up languages. One could say their improvised sounds and gestures are tied to literature by the most delicate of threads. Nevertheless, it is literature: the performance has the air of poetry and usually tells a story, albeit one that lacks words and may hold a different meaning for every member of the audience.

A much newer genre, which also brings words and the stage together and took hold in Estonia over just the last 15–20 years, is spoken word. Although primarily practiced at poetry slam events, it can also be encountered outside the arena, especially when there are more widely-spoken languages and cultures included. Similarly, it’s impossible to say whether the performance or the manner of stringing words together matters more in the unusual poetic form. The two collaborate to create a whole and are most “effective” as such. The audience processes the living literature with eyes, ears, and mind, each of which is of equal importance. This genre’s poetry is diluted when printed, confirming my point – yet at the same time, one can’t say its quality is substandard in the least. There’s also no basis to claim that dense, metaphor-rich philosophical or love poetry is poor if it remains elusive in live performance. Not at all! There’s a time and place for everything.

Jaan Malin, alias Luulur, the grand old man of Estonian literary performance, has also embarked on several experiments that conjoin various forms of art. He has led events that bring together dozens or more artists: instrumentalists, singers (including folk musicians), dancers, painters and/or video artists, actors, and writers. It’s a delight to state that such performances can’t be squeezed into a single genre!

Over the last five or six years, I’ve had firsthand experience in what it feels like to dangle on the border between literature and theater without tilting towards either side. It all began with our “Exercises in Style” performance, which was set in motion by the Estonian writer Jan Kaus. Kaus has published novels and poems but particularly stands out for his profound essays and unparalleled prose poetry. For years, he has likewise taken all kinds of positions on all kinds of stages and produced every kind of noise imaginable, musical and otherwise.

As one might suspect, “Exercises in Style” is inspired by Raymond Queneau’s world-renowned collection Exercices de style, which has been translated into dozens of languages and performed many a time elsewhere. Kaus set out on this adventurous path with stage director Eva Koldits, actor Toomas Täht, and yours truly. From the very start, the four of us were well aware that Queneau’s system is entirely unrestricted and offers unlimited possibilities to come up with new exercises. We gave our minds free reign during rehearsals, the result being exercises that stay true to Queneau’s basic conditions, but are unique in content and form. By the time of the premiere, only three or four original (translated) texts were still used in our repertoire.

Seeing how well the method adapts to the Estonian language and culture, we composed for the Estonian Writers’ Union’s centenary gala a completely new repertoire that remains faithful to Queneau but is 100% rooted in Estonian literature and its key works.

Thus, it’s a fact that Queneau has now contributed two books (the original Exercises in Style, published in Estonian translation in 1997, a selection of our own troupe’s versions, published in 2018), and two plays (both quite independent from the original source) to the Estonian cultural space.

But what is the point of this essay? What is oscillating on the line between theater and literature all about? Having half the people on stage be from a drama background and the other half not, for example? The given situation raises a justified question: what the hell are these amateurs doing climbing up on stage if they feel so out of place there? I must admit that vanity plays a significant role, but a sense of responsibility to the written word is no less important. Given how indispensable words are to both plays (and the keen, precisely formulated literary word in particular), we felt that a couple of writers needed to be represented alongside the actors. It appears the risk was justified. Creative words that differ slightly from an ordinary work of drama and a cast that differs slightly from an ordinary theater troupe produce a strange vibration that one can nearly reach out and touch during the performance.

But that isn’t theater. Nor is it literature.

—

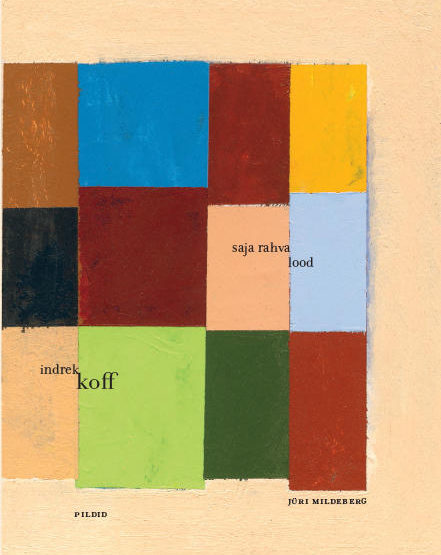

Indrek Koff (b. 1975) is a translator and writer. He has primarily translated Portuguese and French literature into the Estonian language and culture. He has also published children’s books and works for adult audiences that are difficult to pigeonhole into a single genre.